Will Japanese Firms Desert China?

Will Japanese Firms Desert China?(Yicai Global) April 28 -- The Abe government is encouraging Japanese firms to leave China and return home.

As part of its massive supplementary budget, the Japanese government is providing JPY220 billion (USD2 billion) in loans to support firms in relocating their operations from China to Japan. It is offering an additional JPY23.5 billion in loans to help those companies that might wish to move their operations from China to third countries.

Why is the Japanese government doing this? According to the Japan Times, it is worried about the impact that supply chain disruptions in China can have on Japanese manufacturers. It wants Japanese firms to broaden their sources of inputs – by buying more from Southeast Asia – and to return the production of high value-added products to Japan (https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/03/06/business/japan-aims-break-supply-chain-dependence-china/#.XqJHTGgzZPY).

Apparently, the exodus is already beginning. The Nikkei Asian Review reports that Iris Ohyama will likely be the first Japanese company to take advantage of the relocation support program (https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Coronavirus/Japan-preps-first-subsidy-to-company-moving-production-out-of-China). Iris Ohyama makes a range of household products and it currently produces face masks at its Chinese plants in Dalian and Suzhou. These plants procure non-woven and other materials from Chinese suppliers. In June, Iris Ohyama will begin producing face masks for non-medical uses in Kakuda, Miyagi prefecture, with Japanese-sourced materials. Nevertheless, it plans to continue making masks at its two Chinese factories.

Is Iris Ohyama's move an anomaly or does it indicate that a significant amount of Japanese capital is likely to return to Japan from China?

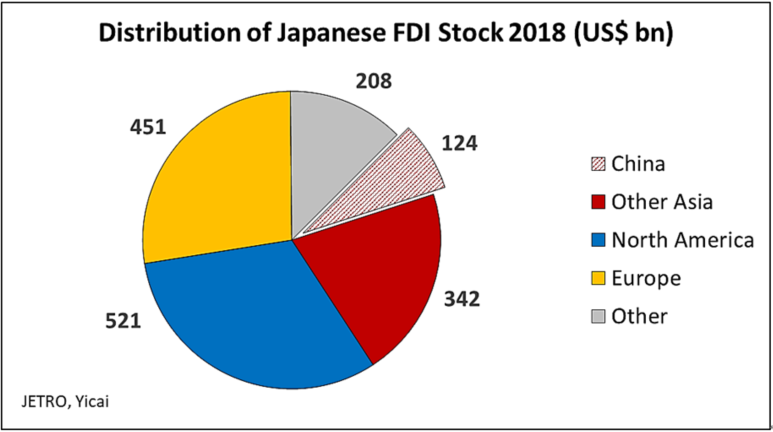

Japan’s stock of foreign direct investment (FDI) abroad totaled USD1.645 trillion as at the end of 2018. The graph below shows how evenly distributed these investments were: 32 percent in North America, 28 percent in Asia, 27 percent in Europe and 13 percent in other countries. Japan’s investments in China totaled USD124 billion or close to 8 percent of the total.

Two points emerge from this graph.

First, Japan’s Chinese investments are small compared to China’s economic importance. The IMF expects China to account for 17 percent of global GDP this year (at market exchange rates), second only to the US’s 25 percent. Moreover, China is Japan’s number one trading partner. In 2019, trade with China accounted for more than a fifth of total Japanese goods trade. By comparison, trade with all of Europe only amounted to 13 percent of the total. From a strategic perspective, Japan does not appear to be excessively reliant on its Chinese investments.

Second, the Japanese government’s relocation support program is equal to less than 2 percent of Japan’s stock of investments in China. So, even if the program were fully utilized, we should not expect that more than a very small portion of Japan’s China-based capital stock would return home.

Notwithstanding rising trade tensions, Japanese firms have continued to increase their investments in China. The graph below shows that the stock of Japanese FDI in China grew by USD5 billion per year, on average, between 2013 and 2018. While the data on Japan’s FDI stocks are not yet available for 2019, the flows numbers suggest growth of a similar magnitude last year. This means that new annual Japanese investments in China have been more than double the size of the Japanese government’s relocation support program.

In recent years, most of Japan’s investments in China have been in the manufacture of transportation equipment and in the wholesale and retail trades. Japanese companies in these sectors are unlikely to go anywhere because their success depends on being close to the Chinese consumer.

Japanese auto manufacturers in China have been doing well in a very challenging market. In 2019, Japanese auto brands increased sales by 3 percent, while those of European brands fell by 2 percent, Korean brands by 18 percent and US brands by 23 percent. Sales by domestic Chinese brands fell by 15 percent last year. Honda and Toyota achieved record sales last year and Japanese brands attained their highest market share since 2011 (https://carsalesbase.com/china-car-sales-analysis-2019-brands/).

In addition to being the world’s factory, China is also the world’s shopping mall and Japanese firms have been successful in cashing in on China’s growing consumer demand. Some companies, like Uniqlo, Muji and Casio are taking advantage of China’s vibrant online retail culture to market their products. Moreover, Aeon, Japan’s largest retailer, is planning to invest USD4.6 billion through 2021 in its Chinese digital business. Other companies, like Asics and Shiseido have levered their extensive bricks and mortar presence in China into sales growth well surpassing that of other markets.

On the one hand, favorable Chinese demand is likely to continue to act as a magnet for Japanese firms. On the other, unfavorable demographics make it challenging for Japanese firms to return home.

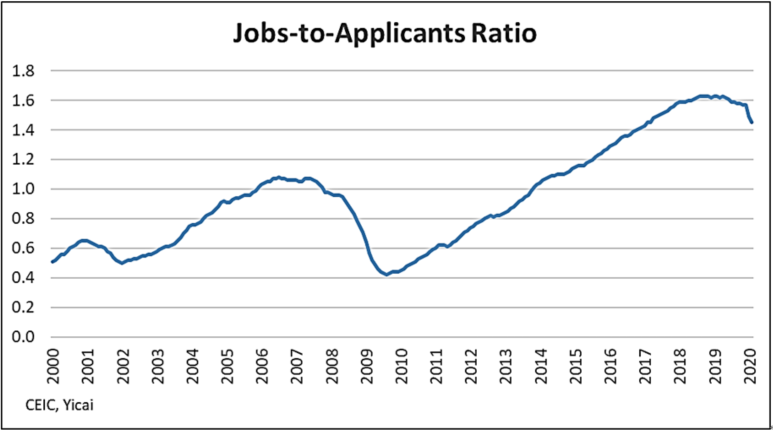

Japan’s society is aging rapidly and, despite the rising participation of women in the workforce, its labor market is incredibly tight. The graph below shows the Japanese job-to-applicants ratio, a key labor market indicator. Even after a virus-related dip, there are still close to 1.4 jobs per applicant. This suggests that it will be difficult for Japan to find the workers needed to re-absorb a significant amount of its Chinese investment stock.

The foregoing analysis suggests that the Japanese government’s relocation support program will only facilitate the return of niche production to Japan.

Even so, no place on earth is immune from an “act of God” that could potentially undermine supply chains. Indeed, Miyagi Prefecture itself was hard hit by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Ultimately, open boarders and a nimble global supply response may be the best disaster management plan.