Why Are the Chinese People So Optimistic?

Why Are the Chinese People So Optimistic? (Yicai Global) Feb.21 -- Late last year, Ipsos, a major market research company headquartered in Paris, published its Global Predictions for 2022. This is not a survey of professional forecasters. Rather, it is an entertaining sampling of public opinion across 33 countries on a wide variety of topics – from the likelihood of one’s government introducing stricter rules for technology companies to whether or not aliens will visit Earth.

While a visit from aliens would certainly be a game-changing event, I find the questions related to people’s outlook for the coming year the most useful part of Ipsos’s survey. The public’s expectations are a critical variable for economic analysis. Since the publication of Keynes General Theory in 1936, the role of “animal spirits” has been used to explain investors’ willingness to undertake new projects. Similarly, economists see “consumer confidence” as important as income and prices in determining people’s spending patterns.

Ipsos gauged expectations by asking survey respondents to agree or disagree with the statement “I am optimistic that 2022 will be a better year for me than 2021”.

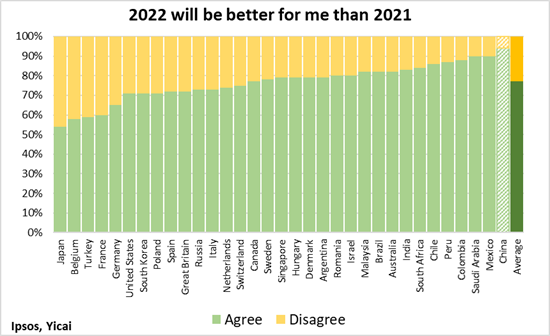

Optimism in China was the highest among all countries surveyed. Ninety-four percent of the Chinese respondents agreed with the statement, compared to 71 percent in the US, 65 percent in Germany and only 54 percent in Japan (Figure 1). Across all of the countries surveyed, 77 percent of the respondents believe that things will improve for them this year. This response is consistent with the average rate of optimism over Ipsos’s eight surveys dating back to 2012 (no surveys were published for 2014 and 2015).

Figure 1

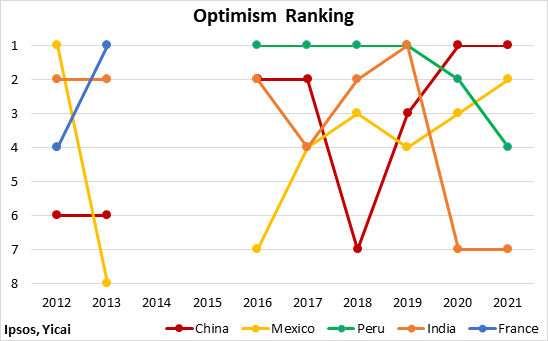

Ipsos’s 2021 survey is the second consecutive one in which Chinese respondents were the most optimistic (Figure 2). While optimism typically runs high in China – Chinese respondents ranked no lower than seventh in the eight surveys – the Peruvians, the Indians and the Mexicans all took turns being even more optimistic in previous years. With the exception of France in 2013, the most optimistic respondents have all come from emerging market countries. As Figure 1 shows, optimism in France has dropped off sharply.

Figure 2

Ipsos’s finding of a high degree of optimism among Chinese people is consistent with other survey data.

In 2016, YouGov declared that the “Chinese people are the most optimistic in the world”, as Chinese respondents were twice as likely as those from any other country to say the world is getting better.

Similarly, in a 2015 study, the Pew Research Center asked residents of 40 countries if children today would be better or worse off financially than their parents. Pew found that the most optimistic about prospects for the next generation were the Vietnamese, with 91 percent saying the children would be better off. They were followed by the Chinese (88 percent), Nigerians (84 percent) and Ethiopians (84 percent). The most doubtful about the next generation’s prospects were the French, Italians and Japanese (all below 20 percent).

So, what makes Chinese people so optimistic?

Martin Seligman, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, is one of the founders of positive psychology. He suggests a link between autonomy and optimism. To the extent that people feel more in control of their lives, they tend to be happier, healthier and more optimistic about the future.

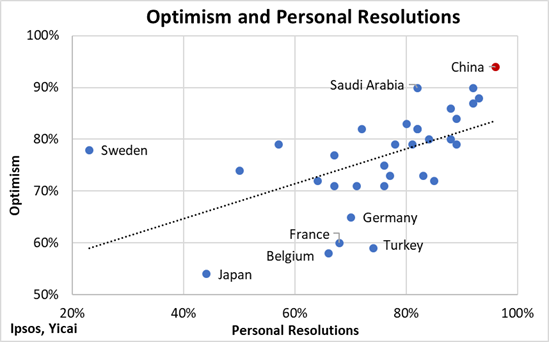

Ipsos’s survey results provide some evidence for this view. Ipsos asks respondents to agree or disagree with the following statement: “I will make some personal resolutions to do some specific things for myself or others in 2022.” In China, 94 percent of the respondents answered affirmatively, well above the 75 percent country-average.

In fact, there is a fairly strong correlation between optimism (those that believe that 2022 will be better for them than 2021) and the intent to undertake resolutions (Figure 3). The Swedes seem to be a bit of an outlier here, as they tend to be optimistic even though they don’t plan on making resolutions. If we eliminated the Swedish responses, there would be a large increase in the correlation.

Figure 3

Ipsos’s results and those of other surveys indicate that residents of emerging market and developing countries tend to be more optimistic than those of advanced countries. This suggests that optimism could be linked to demographic and economic fundamentals.

To investigate this further, I first calculated the “average rate of optimism” for each country over Ipsos’s eight surveys – that is the average percentage for each country that agreed the coming year would be “a better year for me” than the one just ending.

Consistent with the surveys, I found that average optimism was negatively correlated with the level of per capita income – poorer countries were more optimistic than rich ones. Of course, this correlation does not imply a causal relationship. It is hard to imagine why being poorer makes one more optimistic.

The Pew Center found that, within a number of countries, the young are significantly more upbeat about the economy than the old. Since advanced economies tend to have older populations than emerging market and developing countries, differences in the age-structure of the populations could be driving the counter-intuitive correlation between economic development and optimism.

Indeed, it turns out that age-structure not only affects optimism within countries but across countries as well and there is a strong negative correlation between each country’s median age and its average rate of optimism: as countries age their optimism falls.

One would also expect that optimism should be correlated with the rate of economic growth. A faster-growing economy should give people the sense that their standard of living will continue to improve. And there is a good positive correlation between average optimism and the growth of per capita incomes (PPP-based) over 2000-11. Correlations between optimism and other economic variables – such as inflation and the growth of government debt – proved elusive.

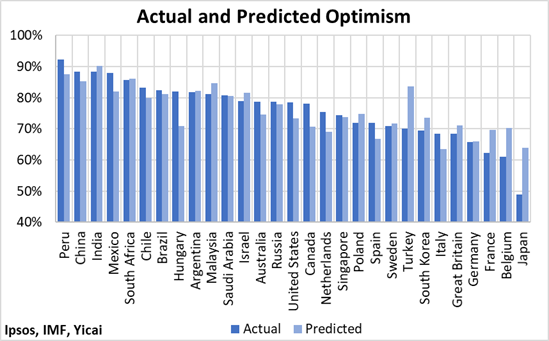

Armed with the median age of the population and the growth of per capita income, I proceeded to model average optimism. This model was able to explain a lot of the differences in optimism between countries (Figure 4). For example, my model predicted that China’s average rate of optimism would be 85 percent and the actual was 88 percent. Similarly, it predicted 73 percent for the US (actual was 79 percent) and 66 percent for Germany (actual was also 66 percent).

Figure 4

Nevertheless, average optimism in a number of countries was difficult to explain. For example, given its age structure and its economic growth, I expected optimism in Japan to average 64 percent, but it was only 49 percent, far lower than in any other country in our sample. Although they are more optimistic than the Japanese, the Turks also surprised me by scoring lower than the “fundamentals” would suggest. On the other hand, the Hungarians were quite a bit more optimistic than the model predicted.

It is worth pointing out some other areas of Ipsos’s survey in which the responses of China’s residents stood out.

Eighty-three percent of Chinese respondents said that it was likely that people in their country will become more tolerant of each other. In contrast, across all countries, only 28 percent thought that greater tolerance was likely and 61 percent thought it was unlikely. This is a pretty sobering result.

The Chinese respondents have the highest faith in cyber-security. Only 19 percent said it was likely that hackers from a foreign government would cause a global IT shutdown. This was half the average across all countries, with respondents in Turkey, Spain and Israel putting the likelihood of a shutdown at 50 percent or more.

Returning to the likelihood of a visit by aliens … respondents believe that the probability of an encounter is increasing. Fourteen percent of the respondents across all the countries surveyed said that a visit is “likely”. This is up 2 percentage points from the 2020 survey. Respondents in India were the most convinced a visit would occur (with 30 percent saying it was likely), while the French and the Belgians were the most skeptical (only 6 percent believe that such a meeting will occur).

It is unclear how people go about assessing the likelihood of a visit from outer space and what it means when they think an encounter is becoming more probable. In contrast, the way in which they perceive their personal situation evolving year-to-year can have real economic impacts. That makes surveys such as Ipsos’s well worth tracking.