The Demise of China’s Private Sector: Greatly Exaggerated

The Demise of China’s Private Sector: Greatly Exaggerated(Yicai Global) July 05 -- Listening to the pundits, you could be excused for thinking that China’s private sector is under mortal attack and is quickly losing ground to state-owned firms that benefit from extensive government support.

Three examples should suffice.

Late last autumn, Michael Pettis wrote that “Beijing has implemented a series of policies that have tightened control over the country’s financial system, undermined private businesses and expanded the role of state-owned enterprises and public-sector investment.”

Around the same time, Kevin Rudd, in his speech to the Asia Society, said that the Chinese leadership has decided “to pivot toward the state” and away from the market.

And, this spring Scott Kennedy stated, “As everyone knows, over the last decade Chinese policies have given greater support to state-owned enterprises (SOEs), giving rise to the idea of ‘state ahead, private back’ (国进民退, guojin mintui).”

So, what do the data say?

According to China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), there were 45 million private enterprises active in China at the end of 2021. This represented a more than four-fold increase from 11 million in 2012. By comparison, Chinese real GDP only increased by 80 percent over the same period. Last year, private firms accounted for 92 percent of all Chinese enterprises, up from a 79 percent share in 2012.

The remarkable growth of the Chinese private sector was no accident. It was the result of a set of policies that supported firm creation by cutting red tape, reducing fees and increasing access to finance.

While the SAMR data show that private enterprises are thriving, many of the businesses in its database are likely to be very small. What do we know about the ability of private firms to grow and establish themselves in the upper ranks of the Chinese corporate sector?

Here we can rely on recent research conducted by Tianlei Huang and Nicolas Véron.

Huang and Véron sort Chinese firms into three categories based on the extent of the state’s equity ownership. They consider those firms in which the state’s ownership is 50 percent or more to be SOEs. Those in which the state owns 10-50 percent are called mixed-ownership enterprises (MOEs). And those in which the state has less than a 10 percent ownership share are classified as non-public enterprises (NPEs).

Huang and Véron painstakingly trace the state’s ownership stake through an often opaque constellation of holding and investment entities to arrive at their assessment of beneficial ownership.

They then apply their ownership classification to the largest Chinese firms ranked by revenue as per Fortune magazine. This “Chinese Fortune 500” comprised 15 firms in 2005, 94 in 2015 and 130 in 2021. In 2021, the top firms in this list were the State Grid (ranked 2nd globally), China National Petroleum Corporation (ranked 4th), Sinopec (ranked 5th) and China State Construction Engineering Corp. (ranked 13th). All of these are SOEs. The largest NPE was Huawei (ranked 44th).

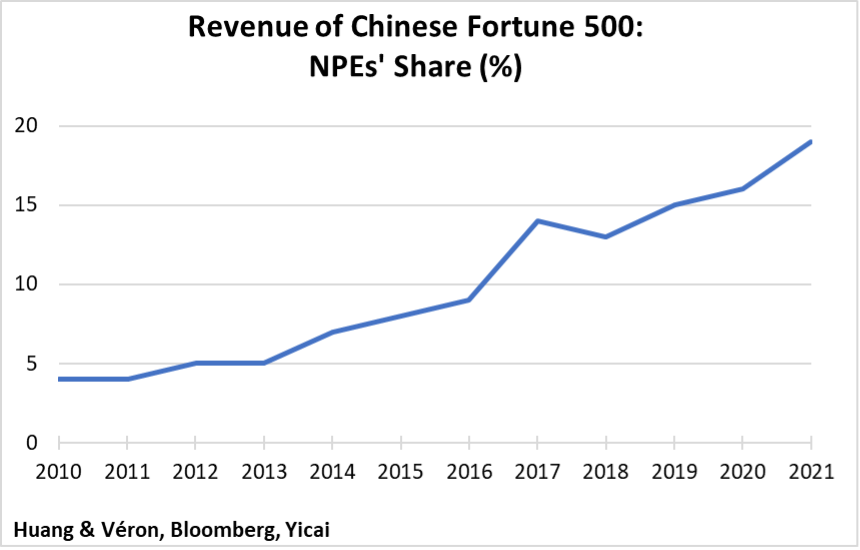

Huang and Véron find that the share of revenue earned by NPEs – essentially private firms – increased steadily, from under 5 percent in 2010 to just under 20 percent in 2020 (Figure 1). NPEs’ share of other important business metrics – such as profits, assets and headcount – with respect to this set of the largest Chinese companies also rose steadily over time.

Figure 1

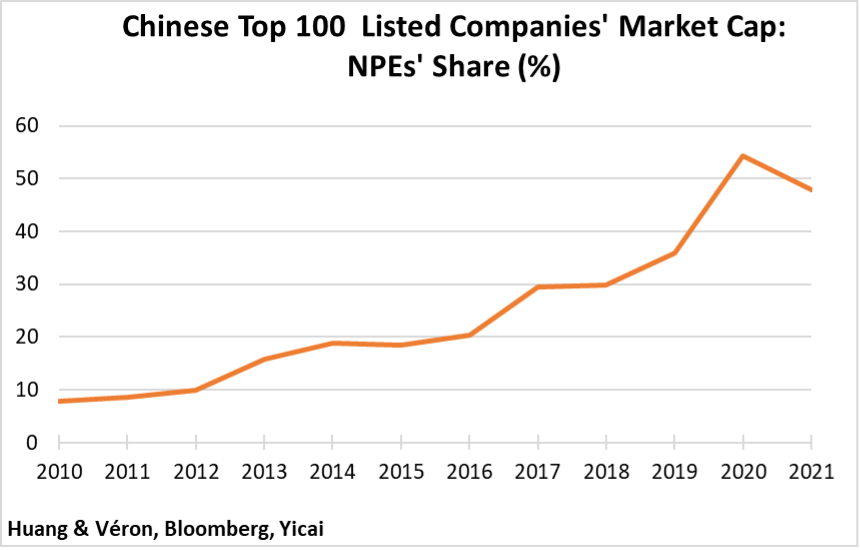

Huang and Véron conduct a second exercise in which they look at the ownership structure of China’s 100 largest listed firms. Here they find that in 2010, NPEs’ market cap was less than 10 percent of that of the 100 largest listed companies. But the NPEs’ share rose to over 50 percent by 2020 (Figure 2). As at the end of 2021, the largest NPEs by market cap were Tencent (ranked 1st), Alibaba (ranked 3rd), CATL (ranked 5th) and Meituan (ranked 7th).

Figure 2

Huang and Véron conclude that the last decade has been one of “unprecedented displacement of state firms away from the top ranks of China’s corporate world.”

The Chinese leadership has consistently said that it wants a mixed economy in which both state-owned and private firms thrive. China’s large state-owned sector makes it unique among major economies. Indeed, state-owned firms provide a useful complement to those that are market-driven.

To some extent, state-owned and private firms often operate in complementary spheres. SOEs typically operate upstream and provide basic materials, infrastructure and finance. Private firms typically operate downstream and produce consumer goods.

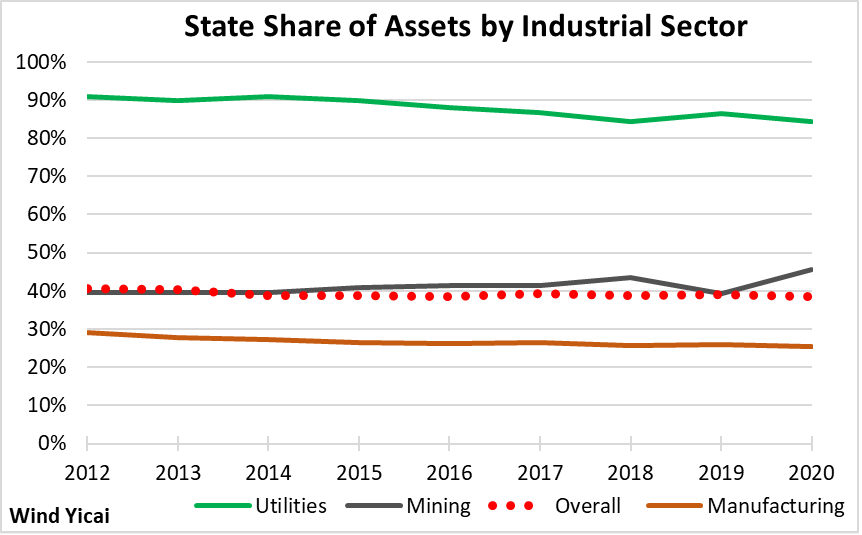

The functional differences between SOEs and private firms can be seen by looking at the distribution of assets across industrial sectors (here we use China’s National Bureau of Statistics’s definition of SOEs). SOEs own a very high share of the assets in the utilities sector. These are firms involved in the production and supply of electricity, thermal power, natural gas and water (Figure 3).

SOEs’ assets only account for a quarter of those in the manufacturing sector and their share has declined in recent years. In contrast, SOEs’ share in the mining sector has crept up and is approaching 50 percent.

Looking at the industrial sector as a whole, SOEs’ asset share has declined marginally from just over 40 percent in 2012 to just under 40 percent in 2021.

Figure 3

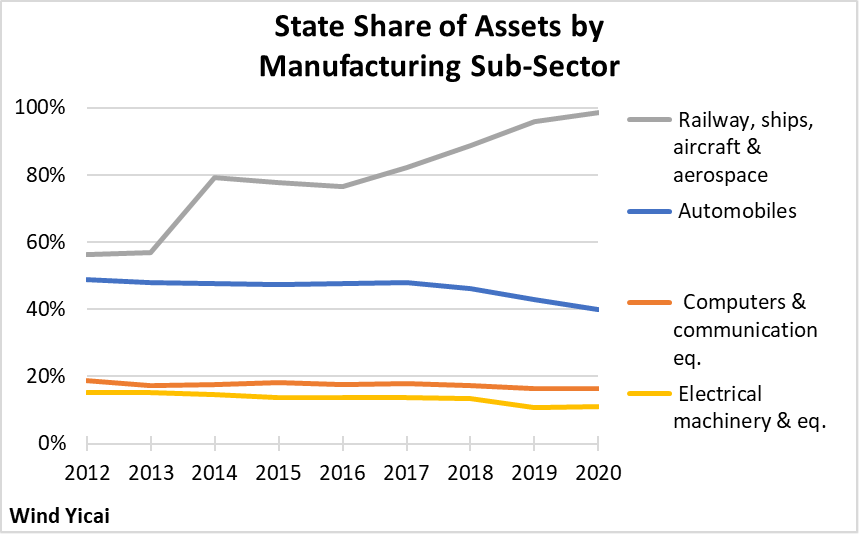

We also see an apparent “division of labour” when we look at the distribution of assets across the largest manufacturing sub-sectors (Figure 4). SOEs dominate rail, ships and aerospace but account for a relatively small proportion of the assets in computers and communication equipment and in electrical machinery and equipment. Autos is a sector in which both SOEs and private firms both have major stakes, although the former’s has fallen over time.

Figure 4

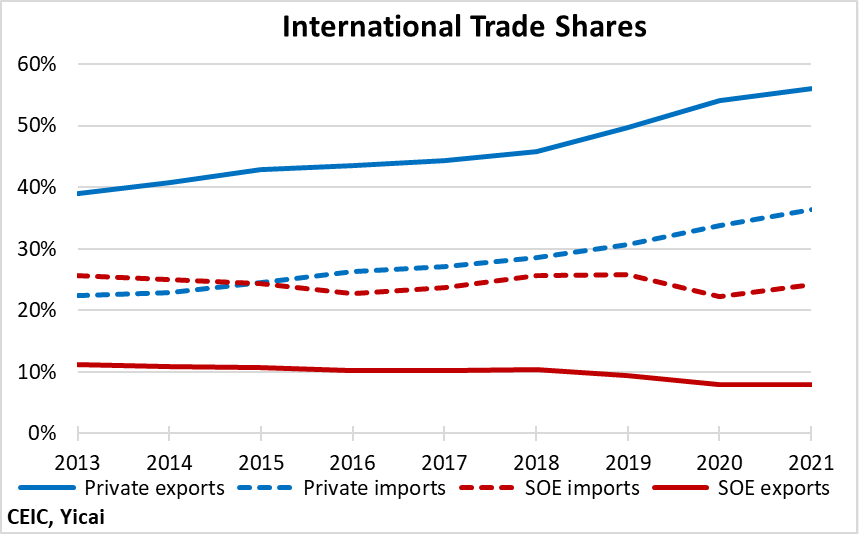

Domestic private firms have also increased their share of international trade (Figure 5). They account for close to 60 percent of all Chinese exports, compared to an 8 percent share for SOEs. Foreign firms (not shown) account for about one-third. Domestic private firms’ share of imports has almost doubled over the past decade, while that of SOEs has hovered around the 25 percent level.

Figure 5

While China’s SOEs do not appear to dominate the economy, they are key vehicles for implementing economic policy.

The SOEs offer the leadership a useful tool for managing the business cycle. In the West, monetary policy has the primary responsibility for demand management. However, as we have seen, in a downturn even a sizable interest rate reduction may be insufficient to induce private sector investment. Moreover, looser monetary policy could simply feed asset-price bubbles.

In 2009 and 2015-16 and likely again this year, SOE investments provide an important offset to the weakness in private Chinese investment demand.

SOEs’ investments can be very useful in situations where the social return exceeds that to private firms. This is often the case for large infrastructure projects. China’s state-owned telecoms are currently constructing the infrastructure for 5G communication that will provide the basis for private firms to develop useful applications. Moreover, SOEs are at the forefront of installing the renewable power that will allow China to meet its carbon neutrality goals.

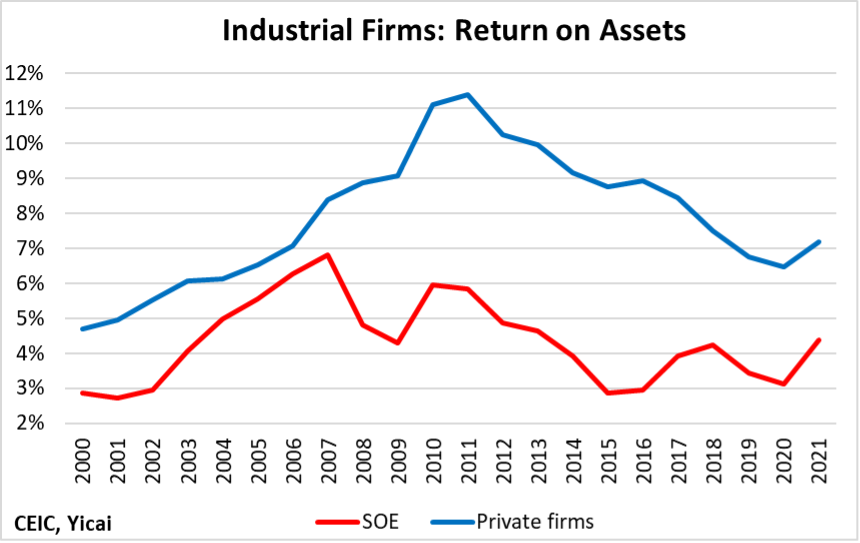

However, the use of SOEs to achieve goals other than profit maximization comes at a cost. In general, their profitability – in terms of return on assets – is lower than that of private firms (Figure 6).

Figure 6

China is in the final year of a three-year action plan for SOE reform, which is designed to make state-owned firms more competitive, innovative and resilient to risks. One of its key initiatives is “mixed-ownership reform” which will allow SOEs to benefit from the private sector’s capital and know-how.

If the data show that the Chinese private sector is thriving, how should we understand the recent regulatory crackdown?

For some time, China’s regulatory environment had been somewhat opaque. Officials were given discretion to adapt rules to local conditions and see what arrangements worked best. While this “constructive ambiguity” probably did support rapid growth, it created other problems. For example, foreign firms have long complained that the regulatory environment was unpredictable and this lack of clarity prevented them from investing even more in China.

Under President Xi, China has increasingly stressed the rule of law over administrative discretion. Moreover, like other countries, China has become increasingly concerned about the platform companies’ market power. Indeed, Chinese platform companies – in particular, Alibaba and Tencent – have become pervasive forces in the economy. They are much more powerful than Facebook, Google and Amazon in the West.

In recent years, the government issued a large number of new regulations, many of which caught the market by surprise. The goal here was not to crush this innovative segment of the private sector. Rather, the regulations provided more transparent guidelines on fair business operations, internet finance and practices that have the potential to endanger national security.

Late last month, the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress voted to pass a revised anti-monopoly law, which will come into effect on August 1. The revisions, which focus on the digital economy, are the first to be made to the law since its implementation in 2008. Clarifying the regulatory framework is welcome as it will further promote China’s private sector’s healthy development.