Have We Seen “Peak China”?

Have We Seen “Peak China”?(Yicai) Sept. 23 -- One of the economists’ most robust empirical findings is inspired by Newton’s law of gravitation. It holds that trade and investment between two countries is proportional to their economic weight, as measured by GDP, and inversely proportional to their geographic distance.

Size matters in these “gravity models”. A country that is growing rapidly will tend to pull trade and investment into its orbit while one whose economic clout is shrinking will become a less important member of the global economy.

A recent report by the Rhodium Group argues that China’s share of the global economy has peaked, that its slowdown is structural and that growth-enhancing reforms are unlikely. If the Rhodium Group is right then China’s economic significance is bound to decline over time.

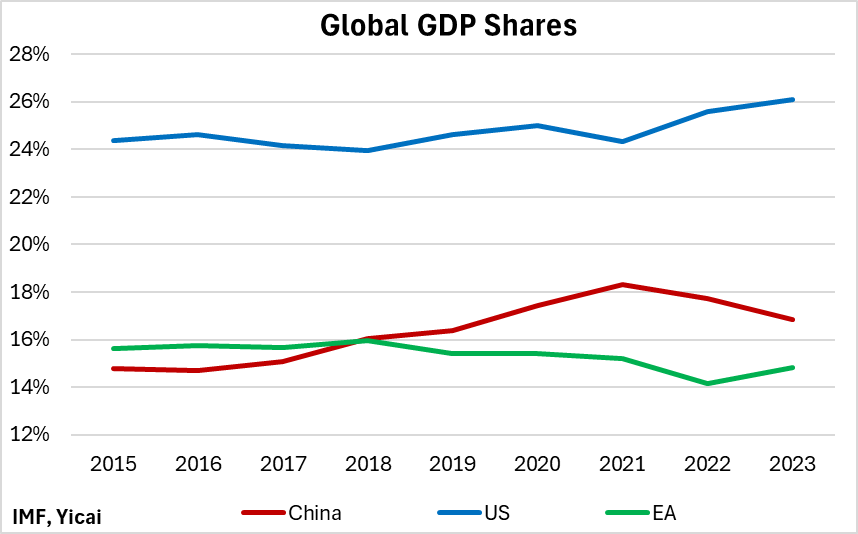

The Rhodium Group argues that a country’s importance within the global economy is best measured by its share of world GDP at market prices and exchange rates. On this basis, China’s share of world GDP peaked at 18.3 percent in 2021 before dropping to 16.9 percent in 2023 (Figure 1). We show the shares of the US economy and the euro area (EA) for comparison purposes.

Figure 1

I believe that the unusual dynamics of the Covid period exaggerate the apparent peaking of the Chinese economy. In particular, high inflation in China’s trading partners and large swings in US interest rates mask a slow and steady increase in China’s economic importance.

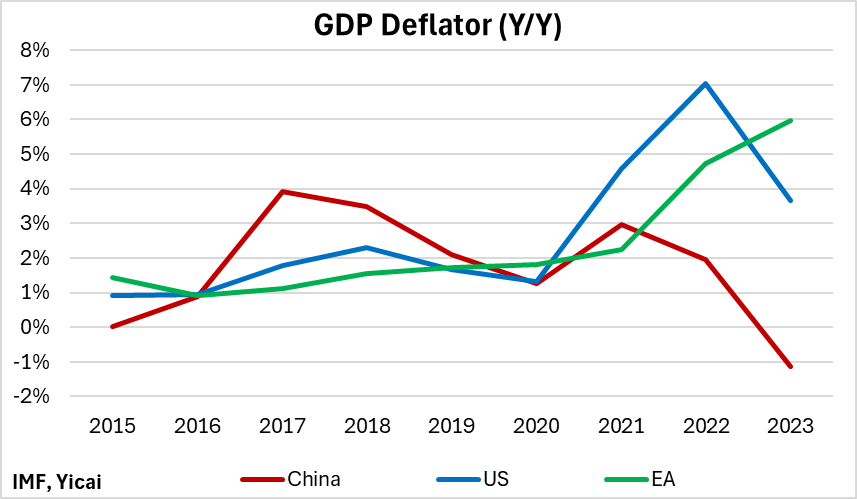

The metric the Rhodium Group has chosen – nominal global GDP – can be broken down into two components: the actual production of goods and services and the prices at which this production can be sold in the market. As a result of Covid’s effects on supply chains and labour markets, the year-over-year change of the GDP deflator was much higher in the US and the EA than in China (Figure 2).Between 2019 and 2023, China’s GDP deflator grew at an average annual rate of 1 percent, while those of the US and the EU grew by some 4 percent.

Figure 2

Relatively high GDP inflation in the US and the EA would increase their nominal GDP shares compared to China, but it would be a mistake to regard these price increases as signs of economic strength. In fact, the contrary is more likely to be true: if a country persistently runs relatively high inflation, it risks losing competitiveness.

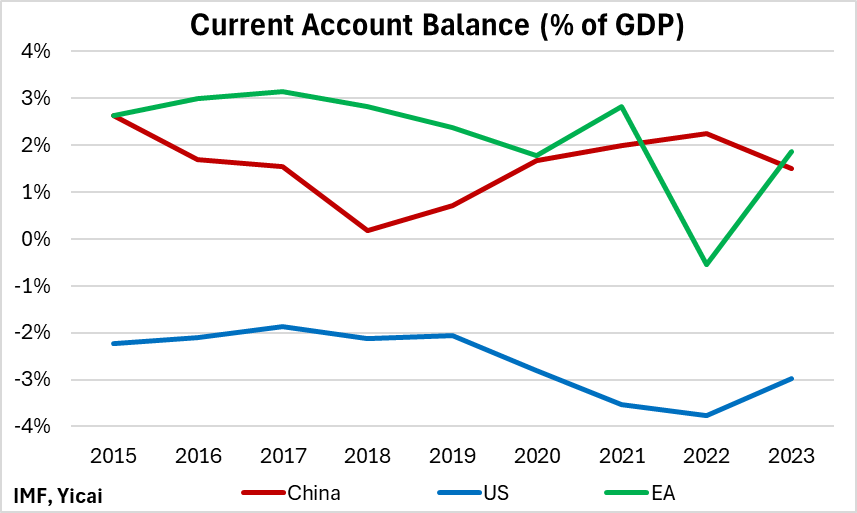

Indeed, the US’s current account deficit widened by 1.2 percent of GDP from 2015-19 to 2020-2023 (Figure 3). Similarly, the EA’s current account surplus shrank by 1.3 percentage points between the two periods. China’s current account surplus only narrowed by 0.5 percent of GDP.

Figure 3

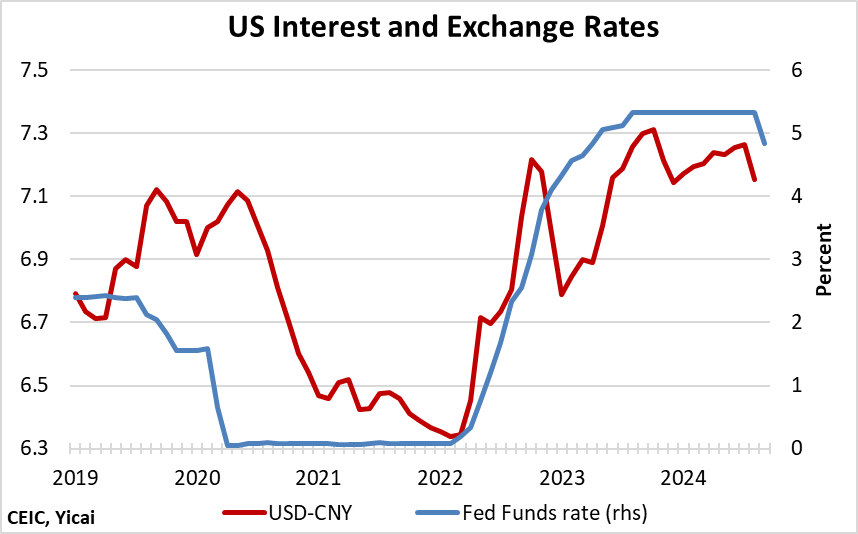

To rein in inflation, the US Federal Reserve began aggressively raising interest rates in early 2021. Higher US interest rates led to an appreciation of the US dollar both on an effective basis and against the CNY. The dollar appreciated by close to 14 percent against the Chinese currency from early 2022 through 2024 to-date (Figure 4). Since nominal GDP shares need to be measured in a common currency, the appreciation of the US dollar led to an increase in the US’s share of global GDP.

Figure 4

The Fed has begun to cut rates as consumer price inflation has come under control. The market believes that rates will continue to fall through next year. This should lead to a depreciation of the US dollar and some reversal of its global GDP share.

We can estimate what the global GDP shares of the major economies would look like if we only considered the actual production of goods and services and ignored the effects of prices and exchange rates on GDP. To do this, we simply take nominal GDP for the world and the three major economies in 2015 and increase them by their rate of real GDP growth.

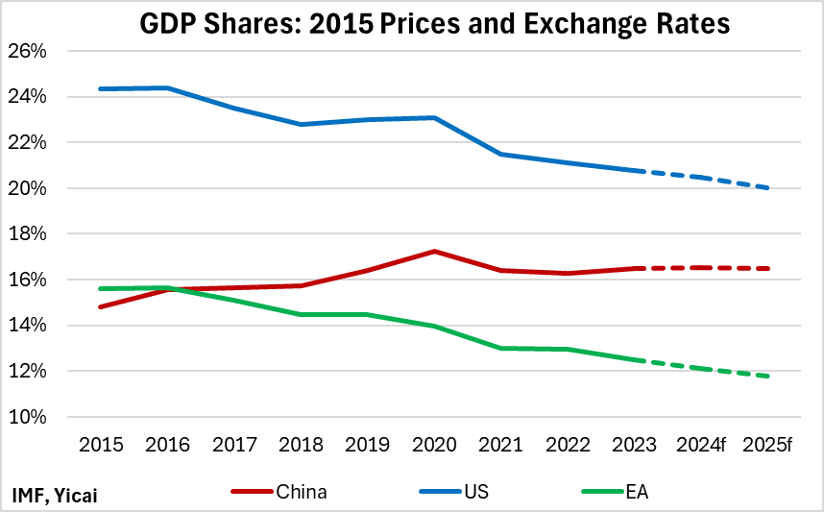

Looking at global GDP in 2015 prices and exchange rates, we see that it is the size of the US and the EA economies that have peaked and are declining (Figure 5). The data for China do show a peak in 2020. However, I would argue that this is the effect of Covid hitting the rest of the world much harder than it did China and not evidence of a structural decline in its global importance.

In its most recent projection, the IMF expects the real growth of the Chinese economy to outpace that of the world both this year and in 2025. That implies that while there could be large temporary movements in prices and exchange rates, China’s underlying economic gravity will continue to increase.

Figure 5