Maintaining 5 Percent Growth: What We Learned from the Two Sessions

Maintaining 5 Percent Growth: What We Learned from the Two Sessions(Yicai) March 19 -- The Two Sessions – the annual meetings of the National People’s Congress and the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference – recently concluded in Beijing. Following these meetings is essential to understand the direction of Chinese economic and social policy. As always, the GDP growth target is the center of attention.

In his Work Report, Premier Li Qiang clearly described the challenges the Chinese economy faces. Global economic growth is insipid. Protectionism is rising and the international trading system has been disrupted. Geopolitical tensions are weighing on investor confidence. In China, weak consumption and payment arrears complicate job creation and income growth.

In the face of these difficulties, Premier Li set the target for GDP growth at “around 5 percent”. The target is the same as 2024’s when GDP growth did come in at 5 percent. According to Premier Li, China needs 5 percent growth to stabilize employment, prevent risks and improve people’s wellbeing.

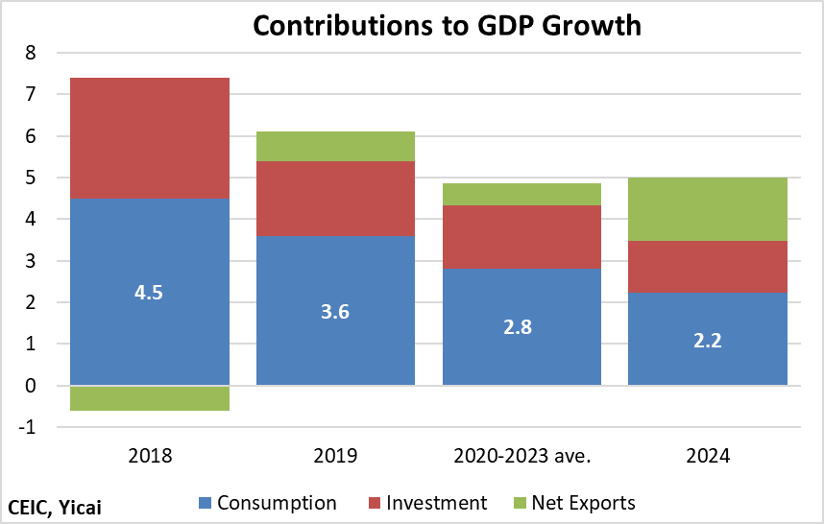

In the absence of strong policy support, meeting the target this year would be challenging. Figure 1 shows the contributions the major expenditure areas made to overall GDP growth over the last several years. I have averaged 2020-2023 to look through the volatility of the pandemic period.

As Premier Li indicated, there has been a clear reduction in consumption’s contribution. In 2018-19, consumption contributed some 4 percentage points to GDP growth. Over 2020-23, its contribution fell to 2.8 percentage points. And last year, consumption only contributed 2.2 percentage points to the 5 percent headline rate.

Achieving 5 percent growth in 2024 depended, in large part, on a 1.5 percentage point contribution from net exports. A contribution of this size is rare. Between 2010 and 2023 net exports’ average contribution was essentially zero.

There is a bright side to this story – China’s exports are competitive and the country continues to gain market share abroad. But it would be unreasonable to expect such a large contribution from net exports this year, given the headwinds from the US’s tariffs. Simulations by McKibbin and co-authors suggest that the 20 percent tariffs recently imposed could reduce China’s GDP growth by 0.3 percentage points this year and by 0.1 percentage points in 2026.

Figure 1

The difficulty in growing net exports puts an extra premium on reinvigorating domestic demand – especially consumption. Premier Li’s Work Report outlines the steps that fiscal policy will take to support domestic demand including through a larger deficit and the issuance of a greater amount of government bonds. The budget document provides the quantitative information to assess just how much China’s proactive fiscal policy will contribute to the attainment of the 5 percent growth target.

The budget document is fairly complex and the full extent of the government’s support for the economy could be under-appreciated, so I want to get a little wonky and go through the fiscal plans in detail.

The general government budget is made up of four accounts: (1) the government itself, (2) the government-managed funds, (3) the state capital budgets and (4) the social insurance funds. All four of these accounts have both central and local government sub-accounts.

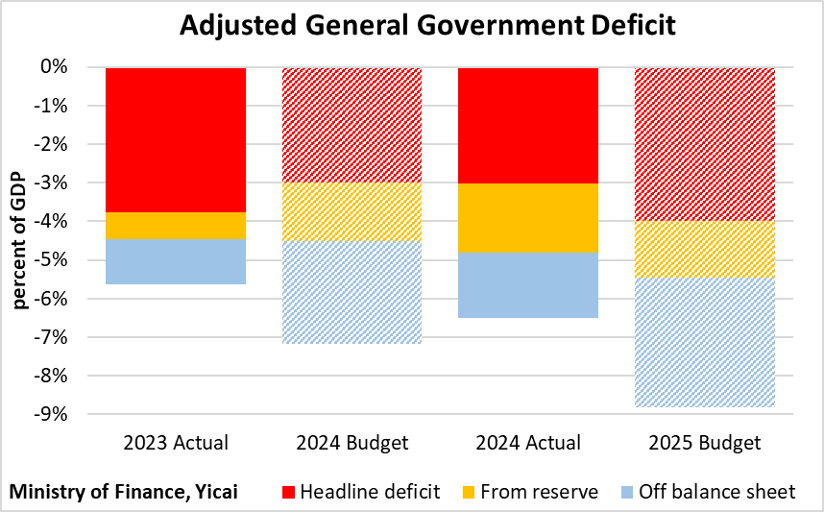

The combined headline deficit of the central and local governments is CNY 5.7 trillion or 4 percent of GDP. The government does its accounting on an accrual basis and the budget document counts the CNY 2.1 trillion drawdown from the stabilization fund as revenue. From a macroeconomic perspective, I think it is best to look at the budget on a cash basis and to treat the drawdown as a funding item. The intuition here is that drawing down a fund does not have the same contractionary effect on the economy as, say, higher taxes do. On a cash basis, the deficit rises to 5.5 percent of GDP. The actual 2024 cash deficit was 4.8 percent of GDP.

The government-managed funds are big spenders. In 2025, they are budgeted to spend CNY 12.5 trillion. This compares to budgeted central and local government spending of CNY 29.7 trillion. Most of the government-managed funds’ revenues and expenses are real estate related.

According to the budget document, the government-managed funds’ revenues equal their expenses. But this is only because it classifies the proceeds from the sale of the ultra-long treasury bonds, the special treasury bonds and the local government special-purpose bonds as revenue. If we consider them funding items, then the government-managed funds are expected to run a deficit of CNY 6.2 trillion or 4.4 percent of GDP. This is up from an actual deficit of 2.9 percent in 2024, once similar adjustments are made.

In 2025, the state capital budget and the social insurance funds are budgeted to run surpluses of 0.2 and 0.8 percent of GDP, respectively. These are down slightly from the 0.3 and 1.0 percent of GDP surpluses actually run in 2024.

Figure 2 puts all of this information together. The “headline deficit” is the combined balance of the central and local governments as widely reported. Summing it and “From reserve” gives us the cash deficit. What I call “Off balance sheet” are the adjusted balance of the government-managed funds and those of the state capital budgets and the social insurance funds.

Summing across all four accounts, I estimate that the Adjusted General Government Deficit is budgeted to reach CNY 12.5 trillion this year or 8.8 percent of GDP. This is an increase from the 6.5 percent of GDP actually recorded in 2024. The difference, 2.3 percent of GDP, represents the budgeted fiscal stimulus.

I think that it is safe to say that this is very significant fiscal support. It represents close to half of the 5 percent growth the government is targeting. In 2024, the budgeted Adjusted General Government Deficit was 7.2 percent of GDP. It represented an increase of 1.5 percent of GDP from the 2023 actual. In the event, the stimulus was only 0.9 percent of GDP, as the actual deficit rose from 5.6 percent of GDP in 2023 to 6.5 percent in 2024.

Figure 2

The budget document also provides useful detail on the nature of government spending.

Local governments will be allowed to use the funds raised from the special purpose bonds to redeem idle land and turn vacant homes into subsidized housing. This will help stabilize the housing market and could catalyse home buying as well as consumer spending more generally.

The central government is budgeting an 8.4 percent increase in transfer payments to local governments, many of which have been hamstrung by a fall in real estate-related revenues. Greater transfer payments will reduce local government austerity and support consumption.

The CNY 300 billion in ultra long-term special treasury bonds will be issued to support the consumer goods trade-in program. This is double the amount allocated last year and it will directly support consumption.

The government’s ambitious fiscal program makes me think of Ne Zha 2 – China’s blockbuster animated film. In it, the eponymous hero famously says,“I am the master of my own destiny (我命由我不由天)”.

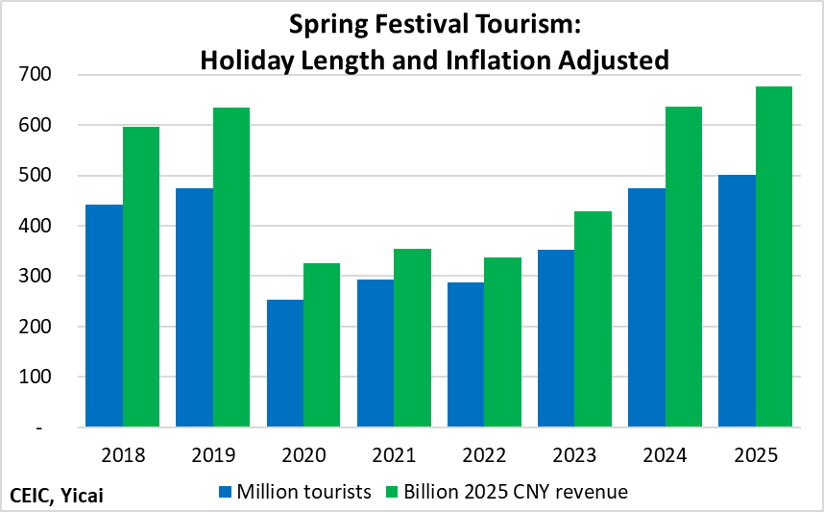

There are welcome early signs that consumer confidence is rebounding this year.

Both the number of travelers and the amount spent over the Chinese New Year holiday were up sharply. To make a fair comparison, I have adjusted the data in Figure 3 to account for the extending of the New Year’s break from 7 to 8 days in 2024 and to account for inflation. On this basis, trips and total spending hit new records, up 5.6 and 6.7 percent, respectively, from 2019.

Figure 3

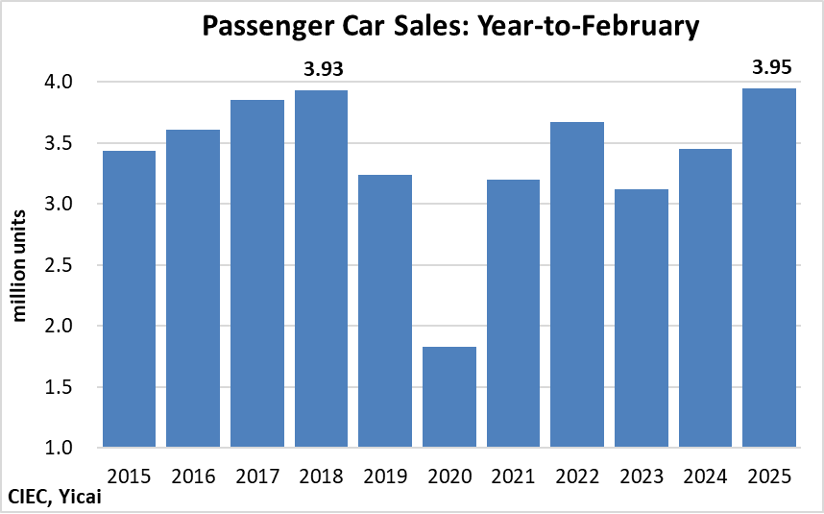

In the first two months of the year, passenger car sales were up 15 percent from the same period in 2024. Indeed, they set a new record by just sneaking past the amount sold in January-February 2018.

Figure 4

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there are emerging signs of recovery in the existing home market. In eleven cities for which I can find consistent data through February, existing home sales are up 28 percent year-to-date.

Table 1: Existing Home Sales Year-to-February

Unit Sales |

| ||

| City | 2024 | 2025 | Change |

| Nanning | 1,391 | 2,378 | 71% |

| Shenzhen | 2,624 | 4,116 | 57% |

| Chengdu | 13,012 | 17,368 | 33% |

| Hangzhou | 3,424 | 4,531 | 32% |

| Beijing | 9,512 | 12,178 | 28% |

| Jiangmen | 803 | 968 | 21% |

| Xiamen | 1,219 | 1,447 | 19% |

| Foshan | 3,423 | 3,908 | 14% |

| Suzhou | 3,791 | 4,277 | 13% |

| Qingdao | 3,696 | 3,895 | 5% |

| Huaibei | 115 | 111 | -3% |

| Total | 43,007 | 55,174 | 28% |

These promising signs and the government’s commitment to strong fiscal support suggest that we very well may see a rotation of demand away from net exports to consumption with GDP growth, once again, reaching 5 percent.