Will We See a Thaw in US-China Relations?

Will We See a Thaw in US-China Relations?(Yicai Global) June 6 -- US-China relations appear to have warmed up in May.

US National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, met with Wang Yi, the Director of the Party’s Foreign Affairs Commission, for more than 10 hours over May 10-11. Both parties reported that the discussions were “” and they agreed to maintain an open channel of communication.

Subsequently, China’s Commerce Minister, Wang Wentao, traveled to the US for an APEC Trade Ministers’ meeting. While there, he spoke to both Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and Trade Representative Katherine Tai. The Chinese and American sides exchanged frank views on trade and investment irritants and they emphasized their commitment to continued dialogue.

On May 21, following the close of the G7 summit, President Biden said that he expects a “” in the relationship between the world’s two major economies. The sentiment is a welcome one since the icy US-China relationship not only complicates the two countries’ economic development, it also has fateful spillover effects for the rest of the world.

Before we consider what steps the US and China might take to further defrost their relationship, let’s review how things got so frigid in the first place.

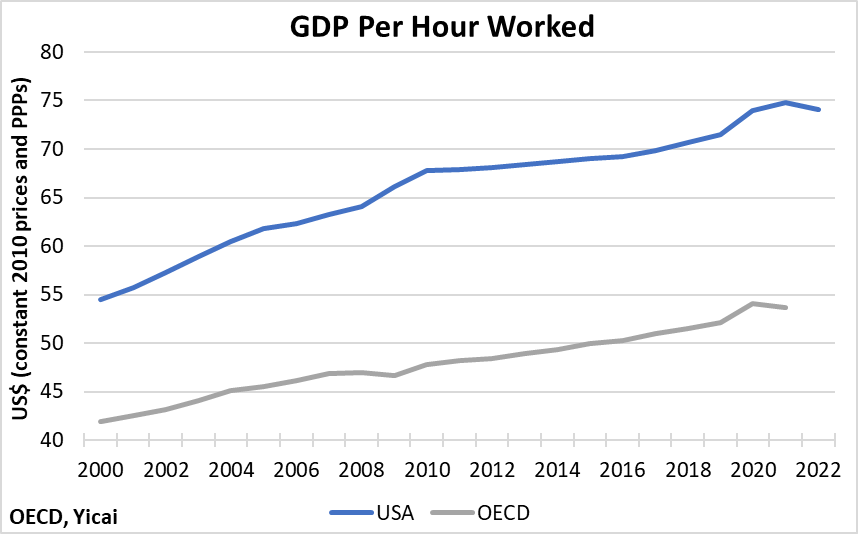

For generations, the US has been one of the world’s most productive economies. In addition, its productivity growth has been relatively rapid. In 2000, GDP per hour worked in the US was 30 percent higher than the OECD average and, by 2021, the US’s productivity advantage had risen to 40 percent (Figure 1).

Figure 1

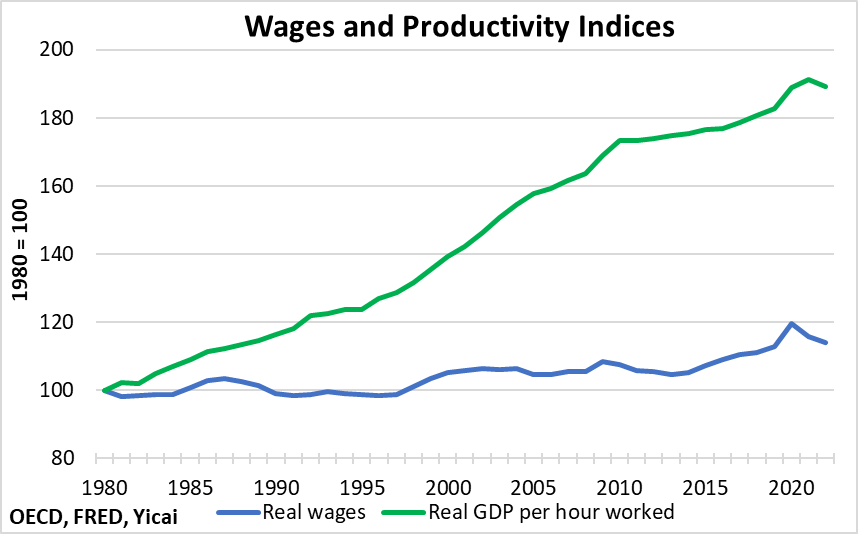

Economic theory suggests that, in a competitive labour market, firms will pay workers according to their productivity. However, over the last four decades, US real GDP per hour worked rose by 89 percent while American real wages only increased by 14 percent (Figure 2).

Figure 2

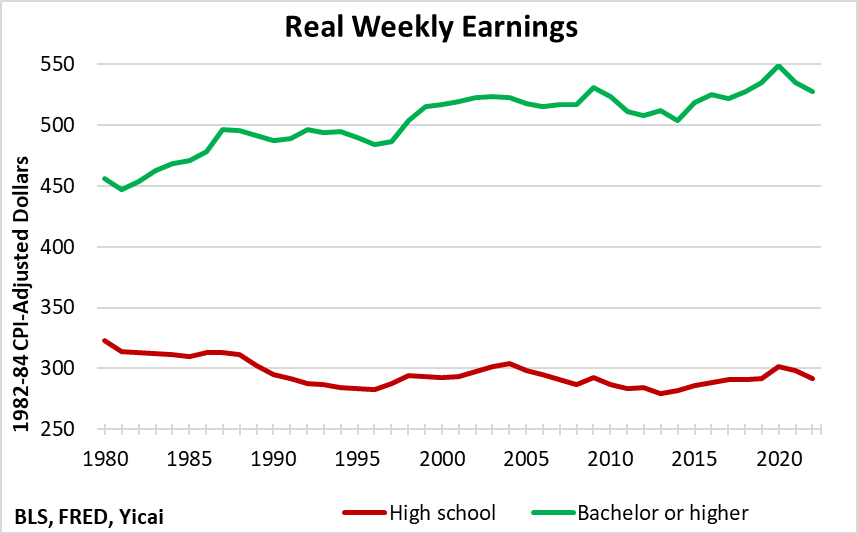

Furthermore, the modest wage increases that did occur were concentrated among better-educated workers. For those with a high school education, real wages actually fell by 10 percent between 1980 and 2022 (Figure 3).

Figure 3

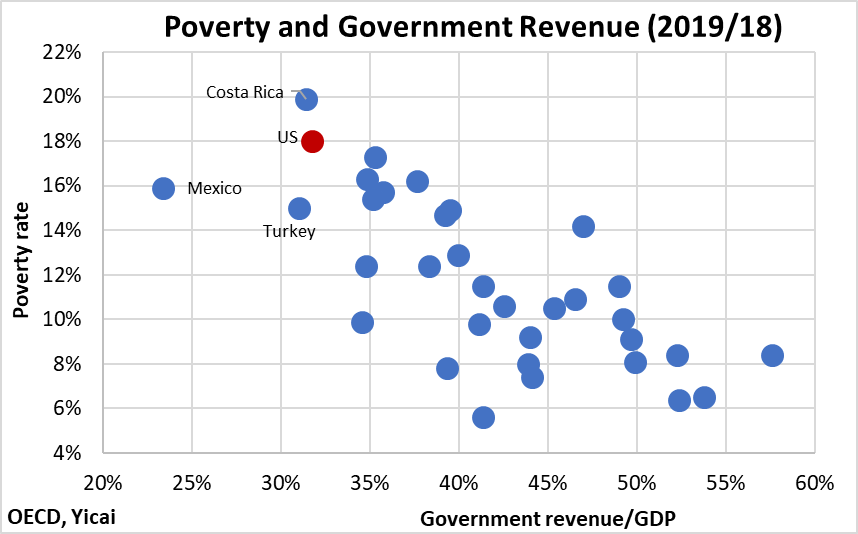

Falling wages resulted in declining living standards for those at the lower end of the US’s income distribution. For some, it meant a decline into poverty.

The OECD defines as those whose income is less than half the country’s median. By this measure, the US’s poverty rate is among the highest in the OECD. The OECD’s data also indicates a strong negative correlation between the poverty rate in its member countries and government revenue as a percent of GDP (Figure 4). This correlation points to the potential for government revenue to finance the provision of public goods and the redistribution of income, which can narrow the gap between poor families and the country’s median.

Figure 4

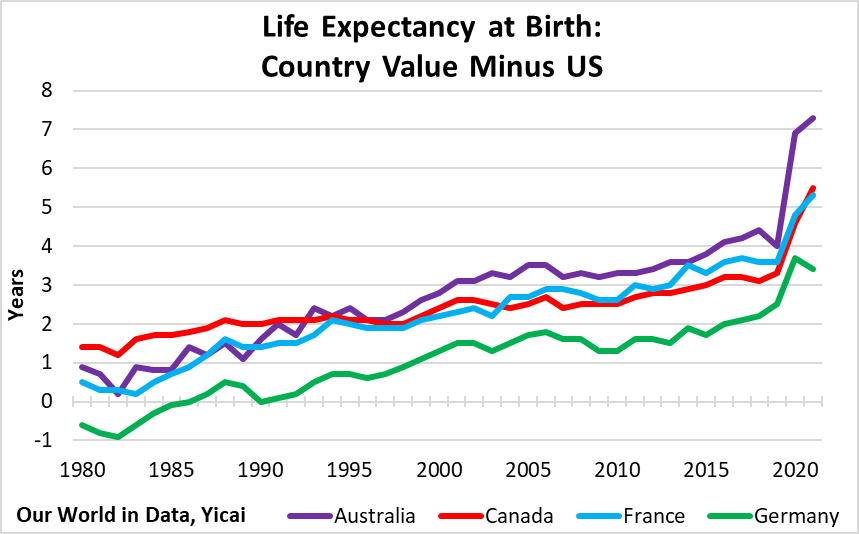

Sluggish real wage growth and unsupportive public policy contributed to the relatively slow growth of the quality of life in the US. Here we look at life expectancy at birth as a rough measure of the quality of life.

In 1980, American life expectancy at birth was just under 74 years, in the same range as Australia, Canada, France and Germany. By 2019, it had risen by just over 5 years. However, in the four other countries, it was up by more than 8 years, on average.

The outbreak of the pandemic put a strain on healthcare systems around the world. But the US seems to have been disproportionally affected. Thus, the life expectancy gap between it and the four other countries continued to widen (Figure 5).

Figure 5

The frustration of many Americans at their declining living standards in the face of the country’s growing prosperity is well documented in Evan Osnos’s . Osnos, a Pulitzer Prize winner who spent eight years in Beijing as a correspondent for the Chicago Tribune and the New Yorker, writes,

“The chasms between American lives had become so vast that the vanishing common ground could no longer carry the weight of American institutions …”

Donald Trump, in announcing his candidacy for president in 2015, famously , “Sadly, the American Dream is dead.” Trump was able to galvanize the disillusioned segments of American society by telling them that “… There are no jobs because China has our jobs.”

Trump frequently highlighted the large trade deficit between the US and China, emphasizing that the US was losing out economically. He argued that China was taking advantage of the US through unfair trade practices and currency manipulation, which led to the loss of American jobs. He promised to bring those jobs back by renegotiating trade deals and taking a tougher stance on China's trade practices.

According to , much of the Washington policy community now believes that the benefits of trade with China are far outweighed by the negative effects on US employment. However, in reviewing the economic literature, Kennedy and Mazzocco report more nuanced results.

find 2.0-2.4 million job losses arising from import competition with China between 1999 and 2011. This is the equivalent of 1.5-1.8 percent of average employment over the period. However, find no evidence of Chinese import competition generating net US job losses, as the employment decline in manufacturing was more than offset by increases in the service sector.

Moreover, account for the positive effect that Chinese imports had on US supply chains and find that the overall effect of the US’s trading with China had a positive impact on both employment and real wages.

In summary, Kennedy and Mazzocco note that there is agreement that some US regions lost manufacturing jobs as a result of trade with China in the early 2000s and that the “China Shock” had dissipated by 2010. Opinions vary regarding its overall impact on the labour market. Crucially, there is consensus that education matters: employment in regions with higher shares of college graduates were less negatively affected by the US’s trade with China.

Until very recently, Americans without college education voted for the Democratic Party, which was traditionally aligned with labour unions. These voters helped elect Barack Obama against John McCain in and against Mitt Romney in .

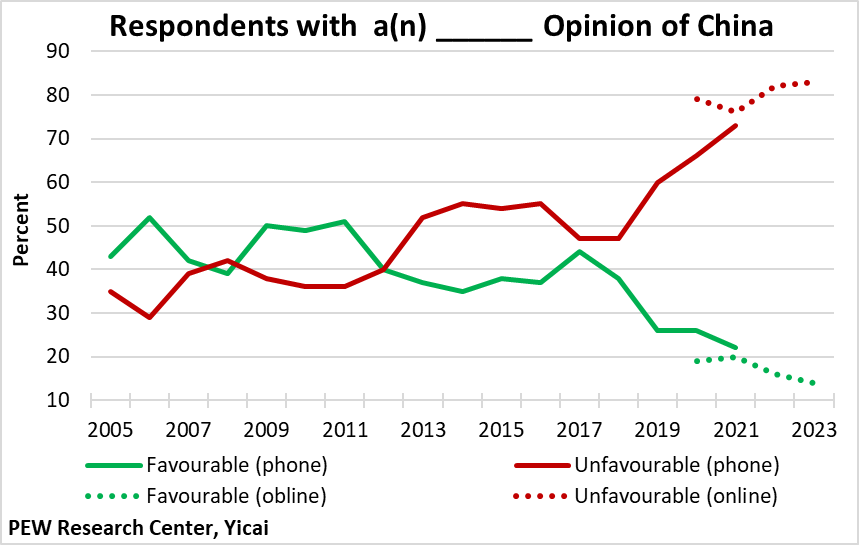

Donald Trump changed that long-established relationship. He had a to voters without a college education and he positioned himself as a champion for blue-collar workers. Trump justified his imposition of tariffs on Chinese imports as a way of protecting American jobs. While the tariffs likely , Trump’s rhetoric had the effect of demonizing China. Prior to electing Trump, the American people had been fairly evenly split on their assessment of China. But their opinion took a decided turn for the worse during his Administration (Figure 6). Sentiment has soured further under President Biden, who risks losing ground with less-well-educated voters should he “go easy” on China.

Figure 6

In this context, how can the US and China warm up their relationship?

Enhanced diplomatic engagement is always welcome. The May meetings were a good step forward. Reportedly, there is a “” of US Cabinet secretaries hoping to visit China, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo. Moreover, US Climate Envoy John Kerry has said that China has to visit “in the near term” for talks.

A cooperative achievement on a major global challenge – like climate change or the crisis in Ukraine – would allow the US and China to build on areas of common interest and show the world what they are capable of achieving together.

But maybe we ought to set our sights a little lower. I have sympathy with the following four “” proposed by journalist Ian Johnson, who is also a Pulitzer Prize winner.

First, the Biden Administration should restart the Peace Corps and Fulbright scholarship programs in China. These programs were cancelled by the Trump Administration as part of an effort to isolate the PRC.

Second, the US government should stop denigrating China’s Confucius Institutes. These are largely cultural centers much like Germany’s Goethe Institutes or France’s Alliances Françaises. They should be allowed to operate off campus in university towns.

Third, the Biden administration should allow Chinese journalists back into the US provided that Beijing again welcomes accredited journalists from American news organizations.

Fourth, the US and China should agree to allow the reopening of their consulates in Houston and Chengdu.

Johnson describes these small measures as “meaningful confidence-building steps” that have the potential to lay the groundwork for tackling more challenging issues in the future. Hopefully, they could help thaw the icy tensions between the two countries.