Why Not Eliminate Corporate Income Taxes?

Why Not Eliminate Corporate Income Taxes?(Yicai Global) April 27 -- The US is looking to build a global consensus for a minimum corporate tax rate of .

From the US’s perspective, it is easy to see why such a proposal makes sense. The Biden Administration is looking to spend on infrastructure projects over the next eight years. It wants to finance these projects by raising corporate income taxes. The Administration worries that higher tax rates could encourage firms to move from the US to lower-tax jurisdictions. Getting international agreement on a high minimum corporate tax rate reduces that risk.

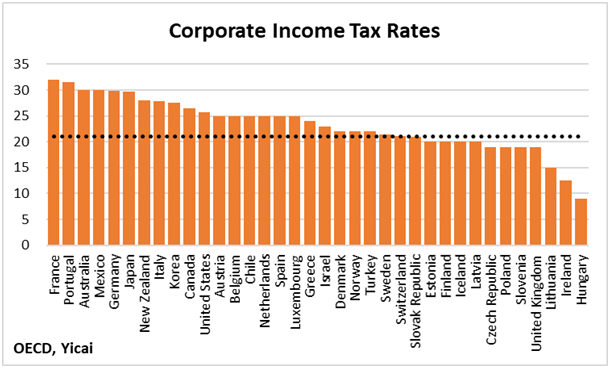

In many countries, including Hungary (9 percent), Ireland (12.5 percent) and Lithuania (15 percent), the corporate tax rate is well below 21 percent (the dotted line in Figure 1). Should a consensus form around the US’s proposal, these countries would be forced to overhaul their tax systems.

Figure 1

However, agreement on a minimum statutory rate will not ensure that the effective corporate tax rate is harmonized among countries. This is because governments give tax breaks to nudge corporations in desired directions. For example, governments often offer tax deductions for undertaking research and development or investing in new plant and equipment.

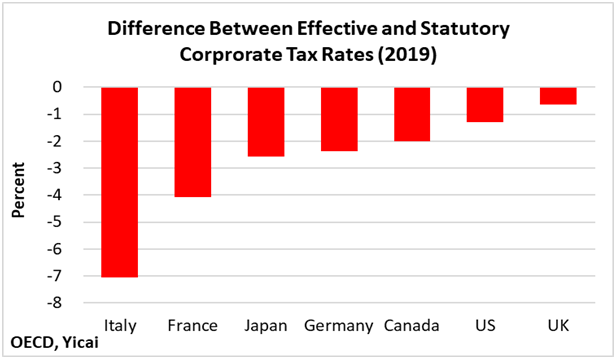

In the G7 countries, the effective tax rate is, on average, 3 percentage points below the statutory rate. Moreover, as Figure 2 shows, the gap varies widely by country. This suggests that countries like Italy and France make greater use of tax incentives than the US and the UK. It also means that ensuring a globally-agreed upon minimum tax is not straightforward.

Figure 2

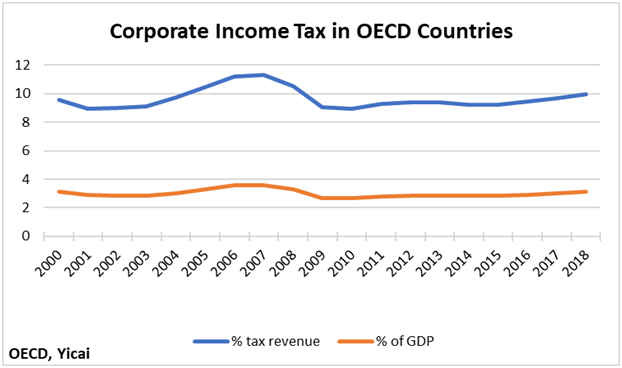

If the US really wants to avoid tax-jurisdiction arbitrage, it could try to build a consensus for a statutory rate of zero. As Figure 3 shows, OECD governments are not especially dependent on corporate income tax to fund their expenditures. Between 2000 and 2018, corporate income tax only represented 10 percent of government tax revenue and 3 percent of GDP.

Figure 3

Eliminating the corporate income tax sounds like a radical proposal. However, moving to a zero corporate tax rate could enhance economic stability, improve the efficiency of a country’s economy and address income inequality.

While a corporation’s interest expenses are tax-deductible, its dividends are paid after-tax. This makes equity a relatively expensive form of corporate finance. As a result, firms prefer increasing leverage to taking on additional equity. It is no wonder that US corporate borrowing from 30 to 80 percent of GDP over the last 70 years.

Excessive debt leads to corporate fragility and greater risk of bankruptcy in times of stress. In addition, corporations can use their debts to and avoid taxes. A zero corporate tax rate would reduce the incentive to over-borrow and increase economic stability.

A country’s corporate income tax system is typically complex and it is expensive for firms to comply with the tax regulations. For example, a by the US’s Internal Revenue Service estimated that it cost American firms between USD92 and USD110 billion annually in compliance costs. This amounts to about one-third of the actual corporate tax paid.

In addition to heavy compliance costs, firms have the incentive to devote significant time and energy to tax avoidance strategies. Eliminating the corporate income tax would allow firms to put the resources devoted to minimizing and then paying taxes to more productive uses. Or the cost savings could be passed on to consumers in the form of lower prices. Freeing firms from paying income taxes could go some way to reverse the slowdown we have seen in global productivity growth.

The optics of eliminating corporate taxes are bad because it appears that the government is giving a tax break to the wealthy. However, some that taxing corporations can actually be regressive, with workers bearing a substantial portion of the corporate tax burden through lower wages. One study found that increasing corporate taxes to raise one euro of revenue would lower wages by 65 cents. The low-skilled, women, and young workers are particularly hard hit.

Eliminating the corporate income tax need not worsen the income distribution. Governments can replace their lost revenue through progressive taxes on incomes or wealth. Indeed, in many jurisdictions, individuals pay a lower rate on dividends and capital gains than on labour income. This is justified because corporate income is taxed twice – once at the firm and again at the individual level. Eliminating the corporate income tax would allow governments to, at the same time, remove these benefits for the propertied.

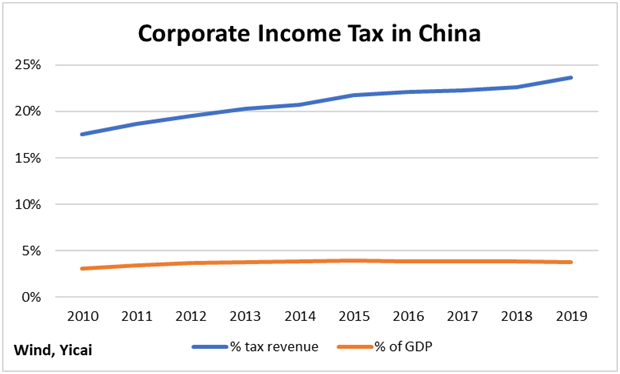

China’s government is much more reliant on corporate income taxes than those of OECD countries. In 2019, Chinese corporations paid CNY3.7 trillion in tax, which accounted for 24 percent of national tax revenue and 4 percent of GDP. Moreover, as Figure 4 shows, the importance of corporate income tax as a source of government revenue has grown in recent years.

Figure 4

Still, even in China, tax reform would make it possible for the country to enjoy the advantages of a zero corporate tax rate without running a huge deficit. The key would be imposing a recurrent tax on residential property to replace the lost corporate tax revenue.

While China taxes the sale of residential property, it does not have a recurrent property tax. I estimate that China’s stock of residential property is worth something like CNY500 trillion, about five times GDP. If the government were to levy a recurrent property tax at 0.75 percent, a rate similar to what we see in North America, it could fully replace the revenue lost from eliminating corporate taxes.

Property taxes are simple to collect, difficult to evade and are inexpensive to pay. done by the OECD suggests that recurrent property taxes are the least harmful to economic growth because they do not affect saving and investment decisions. In addition, such a tax would likely be progressive because the distribution of property is typically skewed to rich households.

In China, a property tax would have the added benefit of increasing the supply of apartments and improving housing affordability. Many apartments in Chinese cities are purchased as investments but are left vacant, rather than rented out. A recurrent property tax would be a good way to keep these apartments occupied and rental costs low, in line with the government’s long-stated principle “housing is for living, not for speculation.”

Around the world, governments have become increasingly concerned about companies that operate globally but choose to “locate” in low tax jurisdictions. Governments are looking to harmonize their tax rules but there will always be incentives to use the tax code strategically.

Setting the corporate income tax rate to zero minimizes “base erosion and profit shifting”. It removes tax-induced incentives to lever up. It reduces spending on tax avoidance and tax compliance. In the context of wider tax reform, it need not worsen – and it might even improve –the distribution of income.

Despite these many benefits, governments face strong political pressures to keep these taxes in place. Perhaps governments could build an international consensus to support them in upgrading their fiscal systems.

So, why not eliminate corporate income taxes?