What is the RCEP and How Will It Affect China?

What is the RCEP and How Will It Affect China?(Yicai Global) Jan. 17 -- On January 1, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) came into effect. The RCEP is a multilateral trade agreement among the ten ASEAN countries, China, Japan, Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

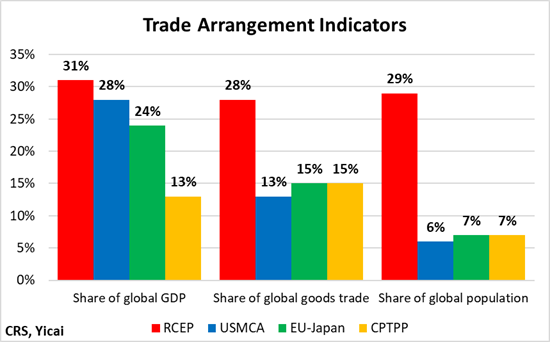

Several metrics presented by the US’s (CRS) show that the RCEP is the world’s largest regional trade agreement (Figure 1). In 2020, it covered larger shares of global GDP, goods trade and population than the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the EU-Japan trade agreement (EU-Japan) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP).

Figure 1

The RCEP was ten years in the making.

It was first mooted during the 2011 ASEAN Summit in Bali, Indonesia and negotiations were formally launched during the 2012 ASEAN Summit in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Talks progressed slowly, in part, due to the large gaps in the parties’ economic development and their differing priorities. An original party to the negotiations, India dropped out in 2019.

The ASEAN countries already had individual “Plus 1” trade agreements with each of the other RCEP members as well as with India. However, over time, these individual agreements gave rise to a “noodle bowl” of rules and regulations.

The RCEP was seen as a way of harmonizing and streamlining trade policy in the region to reduce the cost of doing business. Moreover, it was an opportunity to of economic integration through enhanced commitments on certain services, e-commerce, competition policy and intellectual property rights.

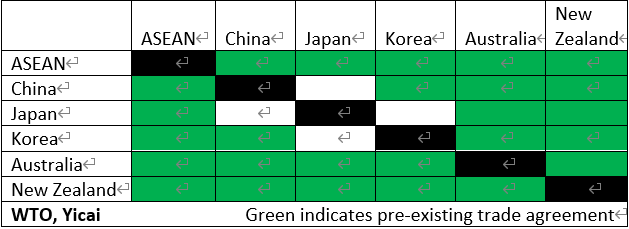

Although the motivation for the RCEP came from ASEAN, one of its key achievements was linking China, Japan and Korea under a single regional agreement (Table 1). Bilateral trade between all other RCEP participants had been covered by some sort of a regional trade agreement (trade between Japan and New Zealand is covered by the CPTPP). China, Japan and Korea initiated trade talks a and, despite 19 rounds of discussions, an agreement remains unconcluded. So, the launch of the RCEP is seen as a testament to ASEAN’s .

Table 1: Regional Trade Agreements Prior to the RCEP

Multilateral deals like the RCEP are often referred to as “free trade agreements”. While tariff reductions are a key part of the RCEP, it is not the case that all of the trade between its members will be tariff-free.

Currently, only 8 percent of China’s imports from Japan (by tariff line) enter tariff-free. Under the RCEP, China will tariffs on 86 percent of the types of goods it imports from Japan. Similarly, Japan will eventually cut all tariffs on 88 percent of the goods it imports from China, up from the 60 percent that now enter tariff-free. Parties to the RCEP agreed to eliminate tariffs of the tariff lines over 20 years and close to two-thirds of intra-RCEP goods trade (by value) will eventually be tariff-free.

Nevertheless, the parties will continue to like agriculture, where 17 percent of the tariff lines are unmodified by the RCEP and the average tariff on these lines is 70 percent. While the RCEP’s 92 percent tariff-free commitment is impressive, it is than seen in the agreements the EU concluded between itself and Japan (97 percent), Vietnam (99 percent) and Singapore (100 percent).

Analysts point to harmonized rules of origin as one of the RCEP’s key achievements. Most traded goods are composed from inputs sourced from many different countries. The rules of origin determine minimum value-thresholds for a good to be considered “Thai” or “Malaysian” and benefit from the lower tariff under the trade agreement. Before the RCEP, ASEAN’s trade was subject to five different sets of rules of origin – one for each of its “Plus 1” agreements. This tended to fragment production in the Asia-Pacific market.

For , 40 percent of their value will need to come from any of the 15 member-countries to qualify for the RCEP’s preferential tariff. These unified rules of origin will lower the tariff rate on inputs produced by RCEP members. Lower costs will, in turn, lead to a deepening of regional supply chains.

With respect to e-commerce, the RCEP members commit not to impose customs duties on electronic transmissions and to protect personal information. While they generally agree to respect the free flow of data, members may make use of exceptions for financial services and for national security.

If disputes arise among its members, the RCEP provides a mechanism for dispute settlement under which a panel of experts can be convened to adjudicate the issue. There is a strong that panellists will have had experience under the WTO’s dispute settlement system. However, disputes arising from investment screening, competition and e-commerce are not covered by the RCEP’s dispute settlement system.

The RCEP creates a permanent secretariat, which can act as a clearinghouse for ongoing negotiations on new commitments. There is also a provision for an overall review of the agreement in five years. Other countries, even those outside of Asia, will be welcome to join the RCEP in 18 months’ time.

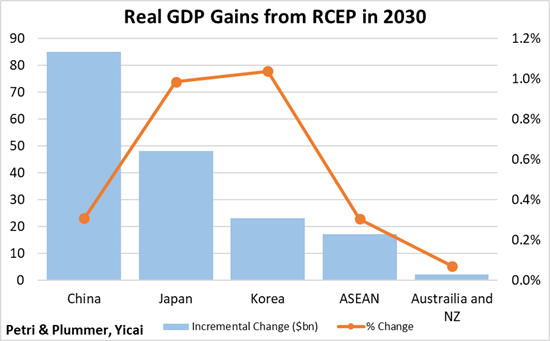

model the benefits of the RCEP. They find that by 2030, trade liberalization will raise the GDP of its 15 members by an aggregate $174 billion or 0.4 percent. The biggest chunk, $85 billion, will accrue to China (0.3 percent of GDP). But the biggest winners from the RCEP, as a percent of GDP, are Japan and Korea both of which see increases in the 1 percent range (Figure 2).

The gains for ASEAN, Australia and New Zealand are fairly small because these countries had already undertaken significant liberalization. Trade among Japan, Korea and, to some extent, China had not previously been part of regional trade agreements and these countries now reap the benefits of the gains from trade.

Figure 2

There are a number of ways in which the RCEP is good for China. Tariff reductions lower the costs of its exports and imports, both of which will grow more rapidly, allowing China to realize its comparative advantage. Moreover, harmonized rules of origin will lead to deeper regional supply chains that will help boost productivity across the region.

Levering the benefits of trade liberalization is one of the key aspects of China’s Dual Circulation Strategy. Along with the RCEP and its “Plus 1” agreement with ASEAN, China has signed . Moreover, it is in the process of negotiating ten new deals (two of which are upgrades to existing agreements) as well as applying to join the CPTPP.

Thus, China’s participation in the RCEP can be seen as part of a long-established pattern of integrating itself ever more deeply with the rest of the world.