What Does De-Risking Supply Chains Mean for China?

What Does De-Risking Supply Chains Mean for China?(Yicai Global) June 29 -- In their May , the G7 Leaders’ presented their new approach to engaging China.

They expressed their desire to forge “constructive and stable relations”. And they said that their approach was not designed to harm China or to “thwart its economic progress and development.”

While they were not decoupling or turning inwards, the Leaders stated that their “economic resilience requires de-risking and diversifying.” Thus, they would “reduce excessive dependencies” in their critical supply chains.

According to international management consultants Oliver Wyman, firms have to manage the risks around doing business in China.

The “China +1” strategy involves sourcing key products from countries such as Vietnam, Poland or Mexico in addition to China. In the “China for China” strategy, firms expand their Chinese supply chains by sourcing domestically produced components. The third strategy, “Re-shoring Strategic Products and Parts” involves firms’ bringing production from China back to the home market, often in response to government subsidies or automation opportunities.

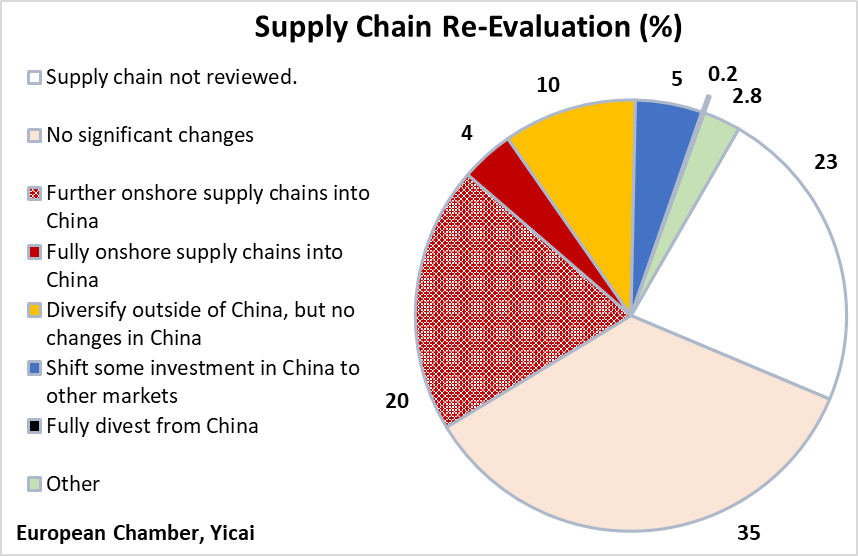

A recent shows the extent to which these strategies are actually being employed by European firms on the ground here. Between February and May, the asked its members whether they had reviewed their China supply-chain strategy in the last two years. The responses are summarized in Figure 1. Of the close to 400 firms that responded, 77 percent said that they had reviewed their strategies. Just over one-third said that they did not expect to make any significant changes in their supply chain operations as a result of their reviews.

The “China for China” strategy appears to be the most popular among the European firms surveyed. A fifth of the respondents said that they planned to further onshore their supply chains into China. An additional 4 percent said that they would fully onshore their supply chains to China.

Fifteen percent appear to be employing the “China +1” strategy. Ten percent of the respondents said that they would diversify future investment outside of China but not make changes within China. An additional 5 percent said that they would shift some investments from China to other markets.

Only a tiny fraction of the European firms appears to be implementing an extreme version of the re-shoring strategy. Among the respondents, just 0.2 percent said that they would fully divest from the China market.

In sum, for the European firms that responded to this question, de-risking is actually positive for China as more firms plan to increase than decrease the scope of their China supply chains.

Figure 1

To assess the resilience of their Chinese supply chains, the European Chamber asked its members whether they imported components for which they were unable to find a comparable domestic substitute. Thirty percent responded that it was impossible to find a viable replacement in China (Figure 2). For those that could find domestic replacements, there were concerns about the quality (25 percent), the compatibility (13 percent) and the costs (10 percent) of the Chinese substitutes.

Less than one-quarter of the respondents said that there were good alternatives available in China for all of their imported components. This suggests that there are limits to which supply chains in China can be fully de-risked.

Figure 2

David Dollar, a Senior Fellow at Brookings’ John L. Thornton China Center, has looked at the recent US experience with . He says that despite the presence of sizable tariffs on Chinese goods since 2018, there has not been a resurgence in US manufacturing. In inflation-adjusted terms, US manufacturing output was only 4 percent higher in mid-2022 than a decade earlier.

Due to the macroeconomic constraints on labour and capital, Dollar does not believe that there will be a generalized re-shoring of manufacturing to the US. He says that absent higher US savings, efforts to subsidize the production of particular goods, like semiconductors or electric vehicles, would simply crowd out other domestic industries.

Dollar also sees no evidence of large-scale near-shoring by which Chinese production is shifted to Mexico, India, or the ASEAN countries. He notes that while China is no longer a low-wage country, it has other advantages that make its supply chain attractive.

He points to assessments of China’s logistics being superior to those of the ASEAN countries, Mexico and India. Indeed, China’s logistics are ranked as high as those of Korea, which is a more highly developed country.

The Financial Times that more than 80 percent of global goods trade is via ship and one aspect of logistics that will act as a break on near-shoring to south- and south-east Asia is the scarcity of port capacity. While China has 76 port terminals able to service the huge vessels that can carry 14,000 20-foot containers, all of the countries in south- and south-east Asia together only have 31.

Dollar also presents evidence – from tertiary school enrollment rates and performance on standardized math tests – that China has outstanding human capital, compared to the countries thought to be candidates for near-shoring. A large pool of educated workers is definitely one of China’s supply-chain strengths.

Intellectual property rights protection (IPR) in China is frequently the butt of US criticism. However, the data that Dollar presents show that the ASEAN countries (on average), Mexico and India do even worse at protecting intellectual property.

In a similar vein, the European Chamber’s survey finds a steady improvement in its members’ assessment of how well the Chinese authorities enforce their IPR laws and regulations. Ten years ago, only 19 percent of survey respondents felt that enforcement was either “adequate” or “excellent”. That share rose to 56 percent in the most recent survey (Figure 3).

Figure 3

A supply chain is only as strong as its weakest link and the scale of China’s manufacturing sector gives producers here an enormous advantage.

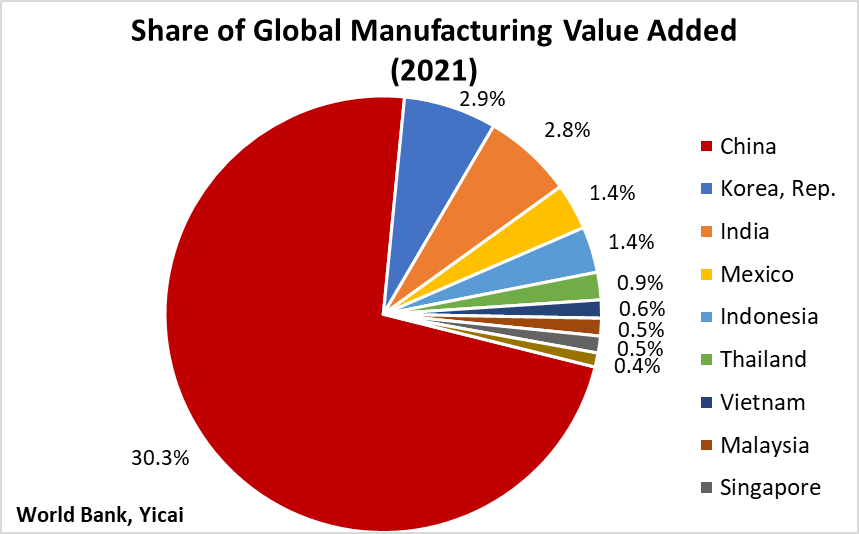

China’s share of global manufacturing value added has more than doubled from 14 percent in 2008 to 30 percent in 2021 (Figure 4). Together, the US and the EU account for 32 percent. Because so much of the world’s manufacturing activity takes place in China, an ecosystem has been developed in which component parts can easily be found or developed.

Figure 4

It is certainly possible that countries with lower labour costs will become attractive locations for the assembly of products with high-value Chinese components. But significant near-shoring would imply recreating China’s ecosystem of component parts somewhere else. Given how much larger China’s manufacturing sector is than those of the candidate countries (Figure 5), an industrial migration of this proportion is hard to imagine.

According to , professors at University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, the costs firms would incur to leave China are simply too high. As long as the ecosystem for manufactured goods remains in China, it will retain a significant share of the world’s manufacturing and it is unlikely that conditions will suddenly switch in favour of other countries anytime soon.

Figure 5

How did China become so dominant in manufacturing?

Part of its success is due to the size of its labour force and its domestic market. Stable macroeconomic policies have also helped. But much of the rise of China as a manufacturing power was the result of how global value chains led to an efficiency-improving division of labour across countries.

Stan Shih, the founder of the Acer computer company, proposed the “smiling curve” to represent relative value added in a supply chain process (Figure 6). For many products, the most value added either comes from upstream activities like design and R&D – or downstream activities – like marketing, branding and customer service. The production process itself is a relatively low value-added undertaking.

Figure 6

Source: OECD (2013), Interconnected Economies: Benefiting From Global Value Chains, .

As the costs of transportation and communication fell, richer Western countries found it to outsource the low-value-added manufacturing portion of the production process to China and concentrate on the upstream and downstream activities.

According to the , participation in global value chains can lead to faster productivity growth. The data suggest that countries that more fully participated in global value chains had stronger productivity growth in those industries that offer greater scope for division across countries.

Does the current emphasis on de-risking mean the fraying of global value chains and a decline in the world’s standard of living?

I have tried to argue that this is unlikely. I believe that the risks to China’s manufacturing base from de-risking are pretty small.