Seeing Is Believing: IMF Upgrades China’s Near-Term Prospects

Seeing Is Believing: IMF Upgrades China’s Near-Term Prospects(Yicai) June 11 -- The Chinese have a saying: without going out, the scholar comprehends all things under heaven (秀才不出门,能知天下事).

The idea here is that the well-educated person is familiar with the deep reoccurring patterns which underlie both the natural world and that of human activity.

One can apply this way of thinking to economics.

Consider a country in which government debt is growing faster than GDP. This sort of fiscal policy is ultimately unsustainable. If unchecked, the rise in leverage will eventually lead to a default and a sovereign debt crisis. Economists can apply such “unpleasant arithmetic” to pretty well any country at any time regardless of particular circumstances.

However, the real world is rarely so simple and the best economists combine an understanding of theory with sound empirics – a thorough grasp of the actual situation on the ground.

The IMF represents best practice in combining these theoretical and empirical approaches. Its maintains an ongoing presence in China. This office typically comprises two economists from Washington who are supported by staff on loan from key domestic institutions like the People’s Bank of China. However, even such a well-resourced team can only provide a partial picture of an economy as large and dynamic as China’s.

To discharge its responsibility of monitoring the economic and financial policies of its member-countries and providing policy advice, the Fund conducts annual . It sends “missions” from headquarters that engage in discussions with senior domestic officials and other well-informed parties. These visits add important detail and nuance to the Fund’s view of countries’ circumstances.

The IMF staff its most recent Article IV mission to China on May 28. Before returning to Washington, First Deputy Managing Director Gita Gopinath and her colleagues conducted a press briefing to share their key findings.

The mission upgraded its forecast for GDP growth in 2024 and 2025 to 5.0 and 4.5 percent, respectively. These represent upward revisions of 0.4 percentage points, in each year, from the projections made in April’s World Economic Outlook (WEO).

Ms. Gopinath said that the sunnier outlook came from the stronger-than-expected growth in the first quarter as well as recent policy measures. She pointed to easier monetary policy, addressing the inventory of finished-but-unsold homes and the funding for equipment upgrades and household durables as being particularly helpful in stabilizing China’s macroeconomy.

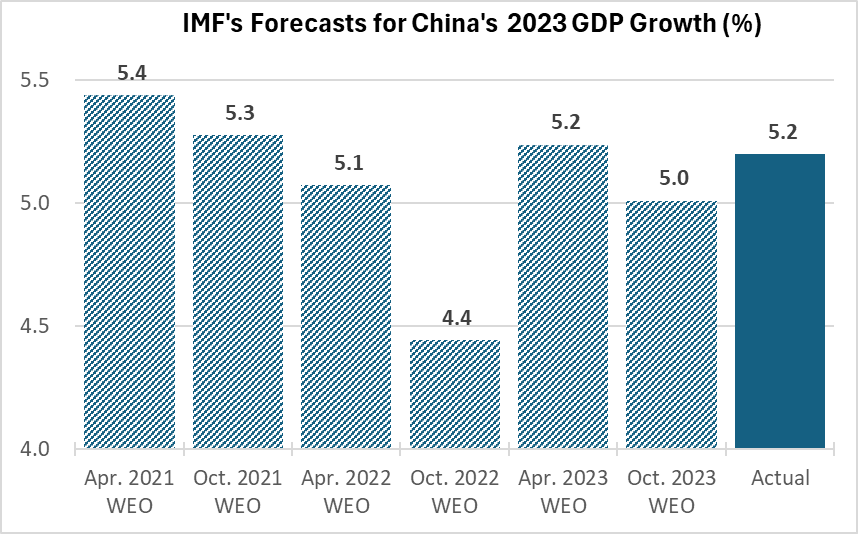

This is the second consecutive year that a strong first quarter led the IMF to mark up its outlook for China’s annual GDP growth. Over 2021-22, the Fund became increasingly negative on China’s prospects for 2023, revising its GDP growth forecast down from 5.4 to 4.4 percent (Figure 1). Subsequently, the release of strong economic indicators early last year led to a 0.8 percentage point upward adjustment in the April 2023 WEO.

Figure 1

Ms. Gopinath offered several suggestions for policies that could further underpin growth.

She recommended that the central government purchase pre-sold unfinished homes. Such a policy would help insolvent developers exit the market. However, bailing out developers has the potential to create and promote even riskier behaviour in the future. In my view, if China wants to continue to use pre-sales as a major source of housing construction finance, it should develop a system whereby buyers’ funds are insured by developers.

The mission believes that fiscal policy needs to walk a fine line between supporting domestic demand and mitigating financial risks. Fiscal policy should be neutral after providing a one-time relief package for the property sector. The mission rightly argues that sustained fiscal consolidation over the medium term is needed to stabilize debt.

On the other hand, with inflation low and output below potential, the mission thinks that there is further scope to ease monetary policy. Some of this easing will take the form of a weaker exchange rate. While a cheaper renminbi would boost China’s net exports, it risks further stoking protectionist responses from its trading partners. In this context, Ms. Gopinath usefully reminds us that while China runs a surplus in its exports of manufactured goods, its imports of services are also large. As a result, net exports’ contribution to GDP growth has been relatively small. Indeed, on average, between 2020 and 2023, net exports only contributed 0.6 percentage points to GDP growth of 4.7 percent.

While Chinese policymakers would welcome the boost to demand and the pick-up in inflation that would come from a weaker renminbi, I think that they are mindful of the lessons of 2015 when a relatively modest depreciation undermined confidence in the currency. I expect them to tread carefully here.

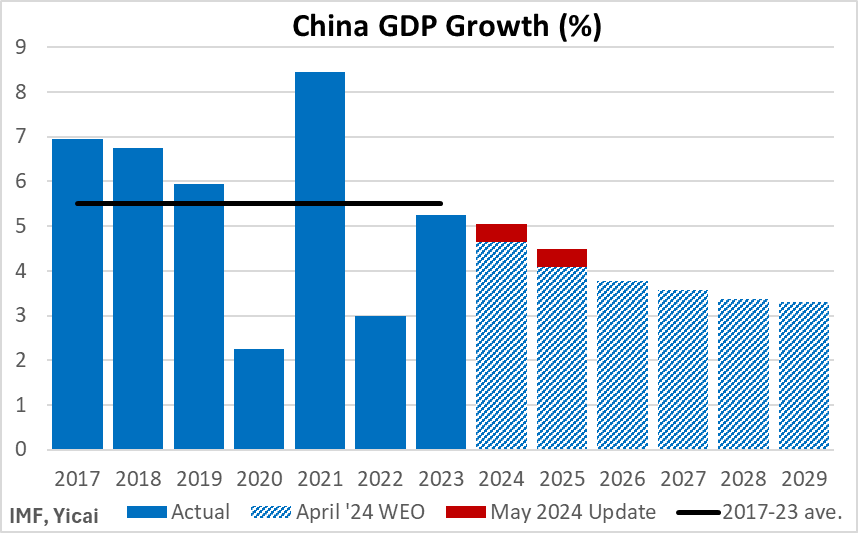

The mission’s optimism about China’s near-term prospects contrasts with its gloomy outlook for growth over the medium term. It expects China’s GDP growth will decelerate from 5.5 percent over 2017-23 to just 3.3 percent by 2029 (Figure 2). According to Ms. Gopinath, this slowdown is the result of unfavourable demographics and slower productivity growth. Moreover, she sees the balance of risks tilted to the downside due to the possibility of a greater-than-expected property sector adjustment and the geopolitical pressures that are leading to economic .

Figure 2

Ms. Gopinath said that achieving high-quality growth will require further structural reforms. Policymakers should prioritize rebalancing the economy towards consumption by strengthening the social safety net and liberalizing the services sector to enable it to boost growth and create jobs.

The IMF has long held that the Chinese economy would be well served by structural policies that rebalance demand from investment to consumption. Its is that the productivity of investment has declined and China’s high investment rate is “excessive”.

While it is true that the productivity of investment has fallen significantly over time, is China’s investment really excessive?

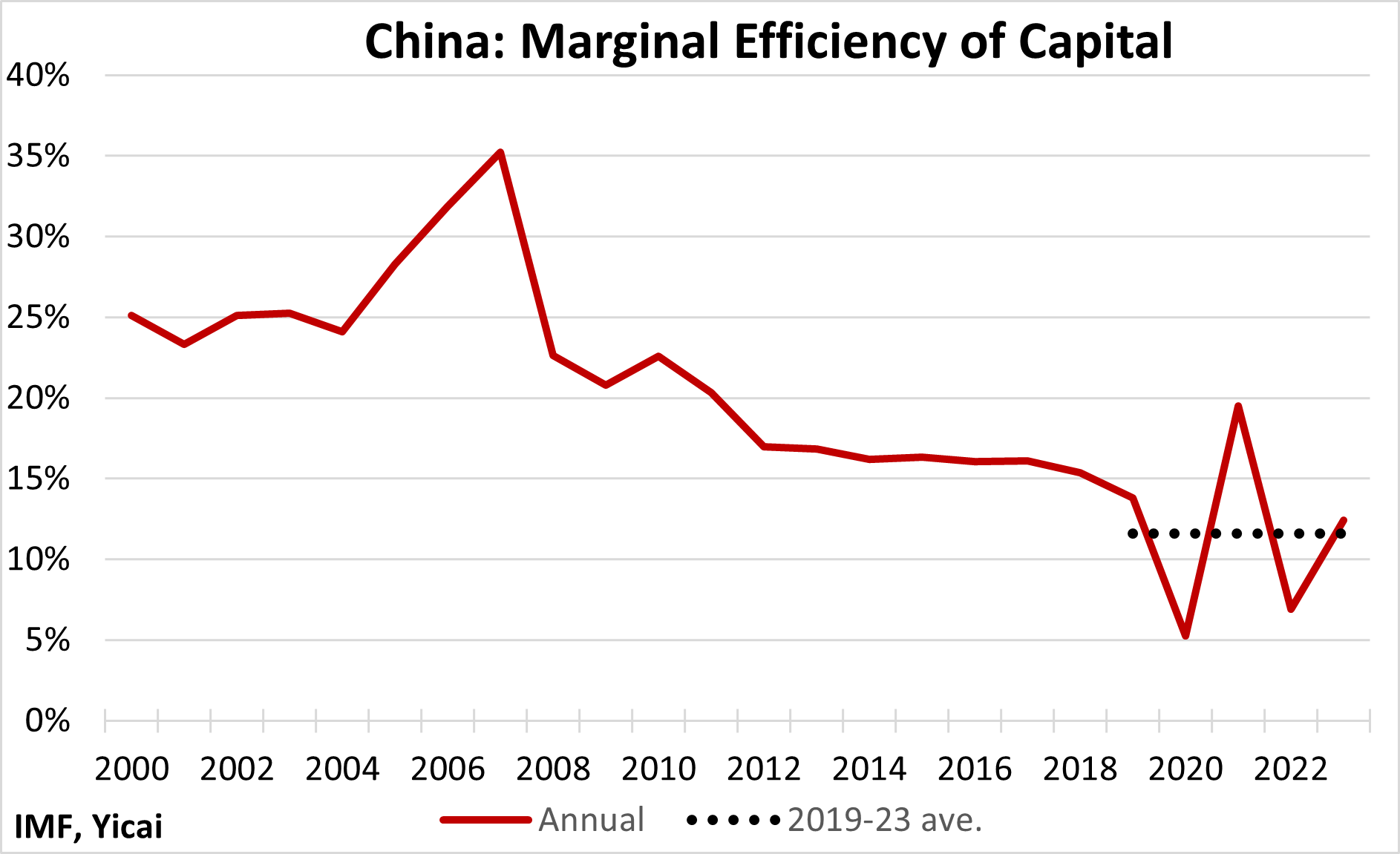

Figure 3 presents the evolution of China’s marginal efficiency of capital – a measure economists use to assess the productivity of investment. It is the increase in GDP that results from the last addition to the capital stock. The marginal efficiency of capital is the inverse of the incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR). It can be calculated as GDP growth divided by the investment-GDP ratio. In the early 2000s, China’s marginal efficiency of capital was very high. It is normal for the marginal efficiency of capital to fall as the capital stock grows and, over 2019-23, it averaged just under 12 percent.

Figure 3

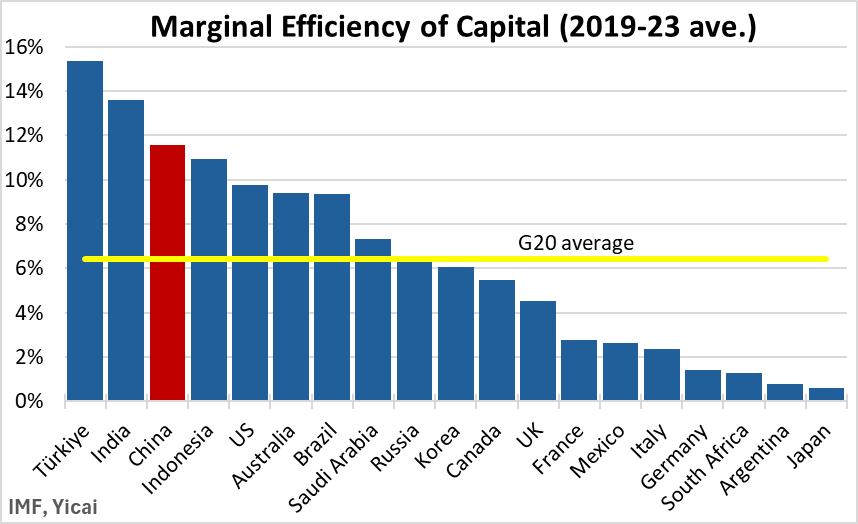

If we compare China’s experience in recent years to those of the other G20 countries, we find that its marginal efficiency of capital has been fairly high. Figure 4 shows that the marginal efficiency of capital in China was third highest among G20 countries in the 2019-23 period. Moreover, by this measure, China’s investments were close to twice as productive as the G20 average.

Figure 4

While this analysis suggests that China’s investments have been fairly efficient, there is still scope to do better. Indeed, further increasing productivity is the bedrock upon which sustainable increases in consumption rest.

According to Steve Barnett, the Fund’s Senior Resident Representative in China, boosting productivity is the most important structural reform that policymakers should address during the upcoming . Mr. Barnett proposes that they level the playing field between all types of firms – state-owned, private and foreign – and create a market-oriented business environment.

Ms. Gopinath cautioned that China’s industrial policy – its support of priority sectors – could lead to the misallocation of resources (reduce productivity) and potentially hurt its trading partners.

Nevertheless, she admitted that green investment is an area in which industrial policy can be beneficial. The Fund has been making the case for the widespread use of and it recognizes that subsidies for green industries also have a role to play.

Ms. Gopinath did not address China’s support for its domestic chip-making industry, given the geopolitical barriers it faces in importing high-performance chips and the machinery needed to produce them.

In assessing China’s medium-term prospects, one has to come to a judgement as to whether slower productivity growth in recent years represents a Covid-related, cyclical slowdown or a deteriorating trend.

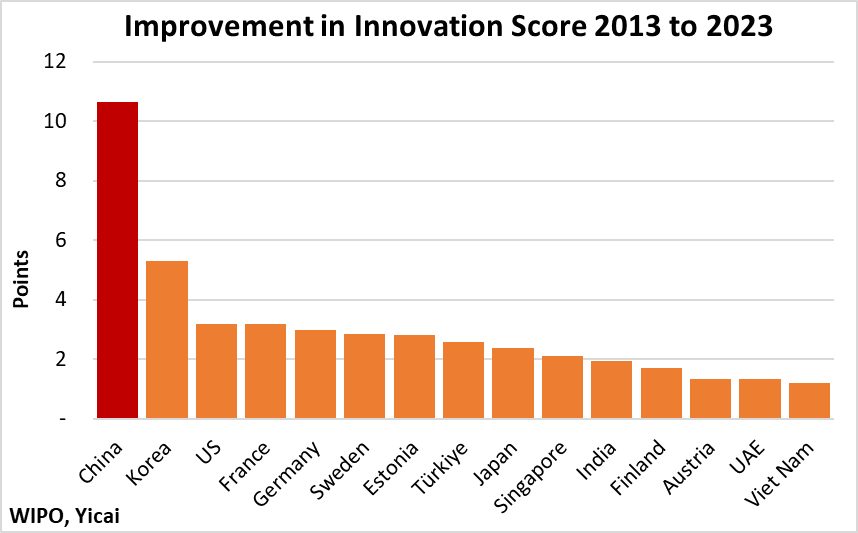

I believe that the IMF is too bearish on China’s medium-term prospects. While it is impossible to observe productivity directly, there are signs that China has become much more innovative. The ranks 132 countries on 80 indicators across five input and two output pillars. Between 2013 and 2023, China’s score improved by over 10 points (Figure 5). This was double the improvement of Korea, which had the second-best increase. The average increase of the 3rd to 7th most-improved economies was only 3 points. As a result, China’s ranking rose from 35th to 12th over the last decade.

Figure 5

China’s innovativeness is one way of explaining how its marginal efficiency of capital has remained high after many years of large-scale investment. It perhaps also underlies the ability of Chinese manufacturers to move up the value chain and become leaders in emerging fields such as electric vehicles.

Back in Washington, the IMF staff are busy preparing their Article IV assessment, which will be presented to the Fund’s Executive Board later this year. This document, which will be freely available to the public, is one of the best sources of information on China’s economy. I look forward to reading it. I also look forward to next year’s mission to see how the Fund’s assessment of China’s medium-term prospects evolves.