Outlook for the Chinese Economy in 2023

Outlook for the Chinese Economy in 2023(Yicai Global) Dec. 30 -- I am seeing more pedestrians in my corner of Pudong but the street life is still not back to normal. Many storefronts remain shuttered. Others have been renovated and are hosting new businesses. The grocery store across the street has become a print shop. The noodle restaurant at the corner is now a foot-massage parlour.

During this season, it is customary to look ahead and project how the economy will perform in the new year. This is never an easy task but, given all of the current uncertainties, forecasting 2023 is especially challenging.

The key variable is, of course, the evolution of Covid in a much more permissive policy setting. It now seems that almost everyone we know has been infected. If they are not sheep (the colloquial term for those that test positive) then they are shepherds, who spend their time caring for family and friends.

Covid’s ability to wreak havoc on the Chinese economy will depend critically on people’s willingness to vaccinate themselves.

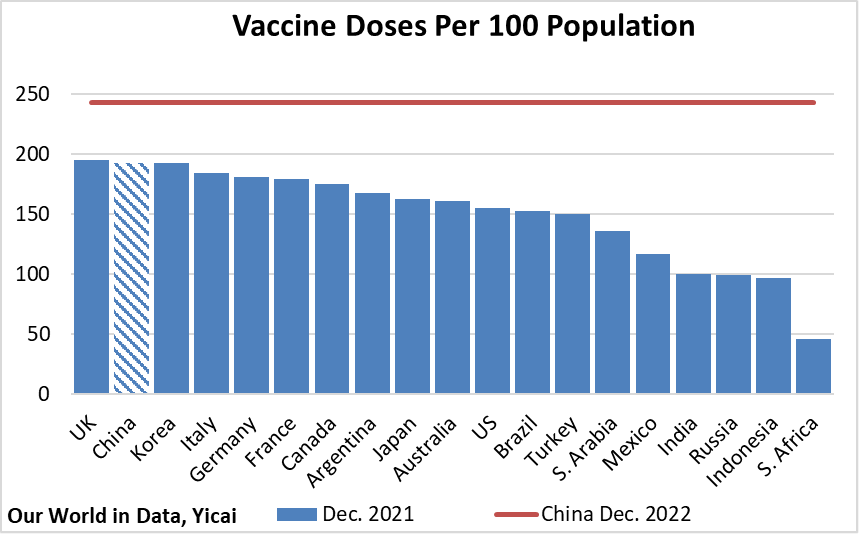

This Omicron wave is breaking about a year later here than it did in other countries. This lag has allowed China to achieve a relatively high vaccination coverage. In December 2021, the average vaccination rate across the G20 countries was 150 doses per 100 people (Figure 1). At 193 per 100 people, China’s rate was already among the group’s highest. A year later, China’s vaccination rate stands at 243 doses per 100 population, suggesting that the outbreak here could be somewhat less deadly than elsewhere.

Figure 1

Still, more needs to be done to protect vulnerable groups. In particular, older people should receive three doses of the Chinese-made vaccines, which are just as effective as mRNA shots in preventing severe illness or death. However, China’s National Health Commission that 30 percent of those over 60 and 58 percent of those over 80 have not yet received three doses.

There’s a renewed push, at the grass-roots level, to encourage older folks to roll up their sleeves. The video screen at the entrance to our community runs a short cartoon telling old people that vaccinations are safe and encouraging them to get their shots. More practically, our neighbourhood committee is providing free weekly vaccinations, for those 60 and over, at their conveniently-located office.

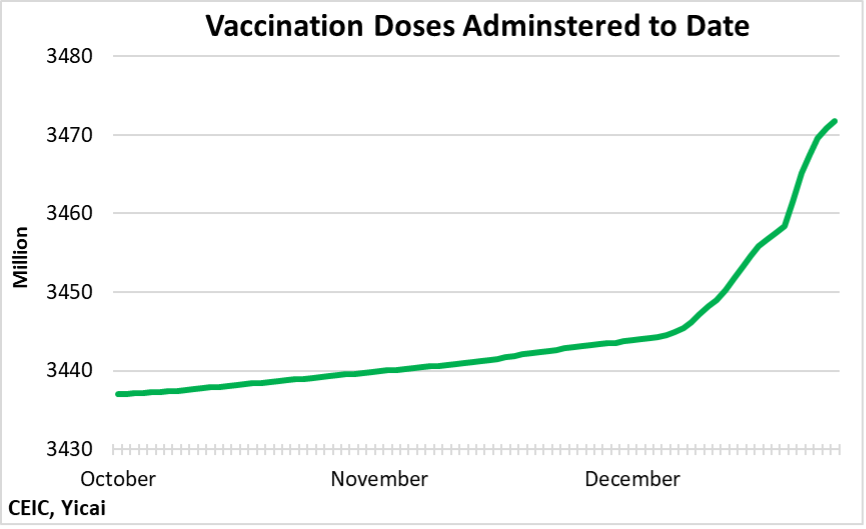

While vaccine hesitancy remains a problem, the data show a marked rise in the number of vaccinations China has administered in December (Figure 2), which is an encouraging sign.

Figure 2

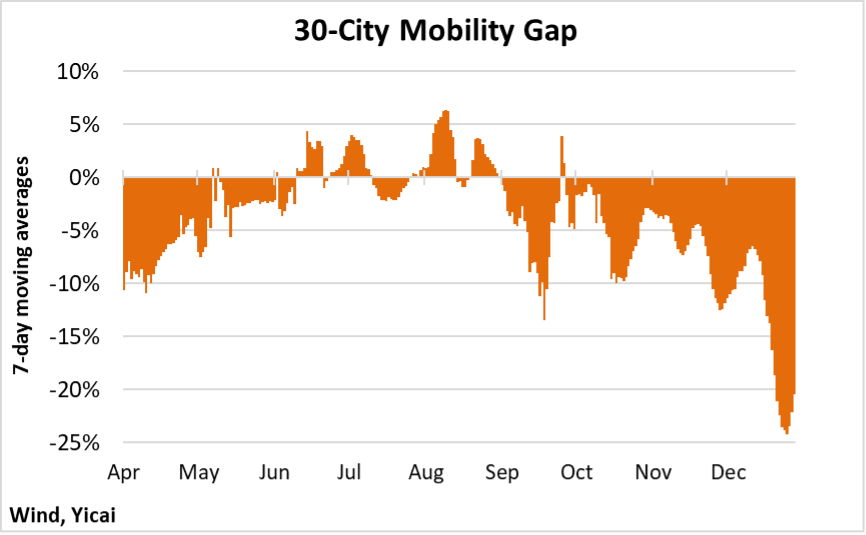

While it is difficult to assess the scale of new infections and the seriousness of the cases, the mobility data suggest that people are staying home in droves.

Our “mobility gap” shows the situation in December is more acute than it was in April (Figure 3). This is not surprising. While the wave in the spring was largely confined to Shanghai and Jilin Province, this one has washed across the country.

Figure 3

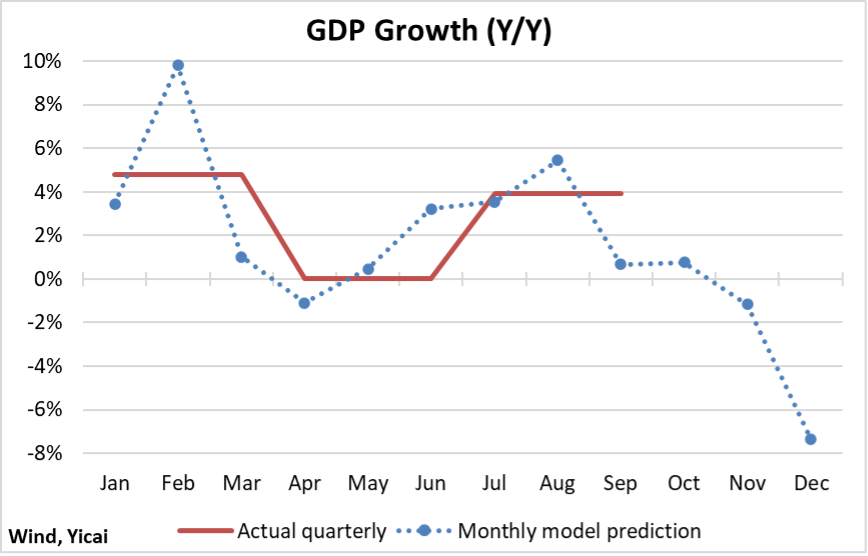

The low mobility numbers bode poorly for economic activity in December. Our simple model, which uses the mobility gap to predict GDP-consistent, monthly economic activity, points to a sharp contraction in the economy (Figure 4).

Figure 4

It is very likely that the fourth quarter will look an awful lot like Q1, with GDP declining on a Q/Q basis and showing no growth at all year-over-year. Such an outcome would bring growth for the year as a whole down to 2.3 percent, about the same rate as was recorded in 2020.

What does that mean for the economy in 2023?

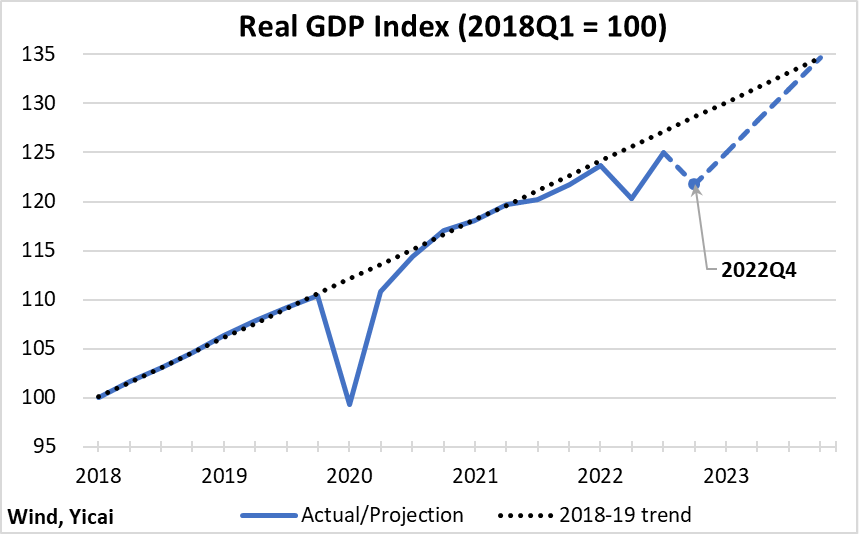

I assume that this wave of Covid is a serious but, ultimately, temporary shock to the economy. Given the relatively high vaccination rate among the working-age Chinese population and Omicron’s relatively low virulence, I do not foresee the sort of labour-supply problems that plagued other countries. I believe it is reasonable to expect the economy to return to its pre-Covid trend by the fourth quarter of the year. Should GDP follow the path illustrated in Figure 5, growth in 2023 would come in at 5.8 percent for the year as a whole.

Figure 5

The composition of growth in 2023 is likely to differ from what we have seen in recent years. Net exports are unlikely to make a contribution. We should see some rebound in consumption and investment – mostly state-led – will likely be a more significant driver of growth.

The external environment will be challenging in 2023.

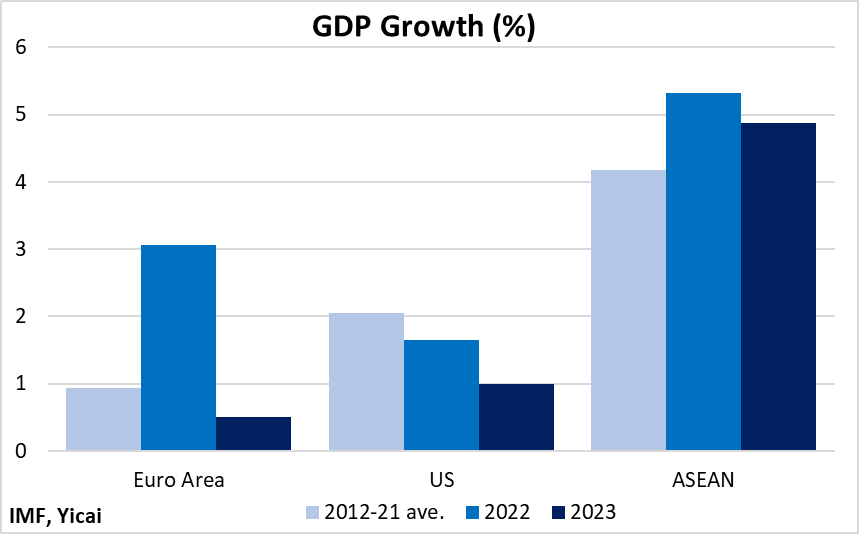

In its October , the IMF projected economic activity in China’s major trading partners to slow significantly between 2022 and 2023. In fact, it only expects growth in the Euro Area and the US to be half as rapid as their 2012-21 averages (Figure 6).

Figure 6

Net exports had contributed about a percentage point to China’s GDP growth in recent years but it’s hard to see them helping out much in 2023. It is, therefore, no wonder that the (CEWC), which was held in Beijing in mid-December, emphasized the need to support domestic demand.

According to the CEWC, expanding consumption will be a priority and it singled out improving housing while supporting the purchase of new energy vehicles and elder-care services.

Policy will promote the stable development of the real estate market, including making sure that buildings under construction are ultimately delivered to their purchasers. Given the financial risks associated with highly-levered developers, the CEWC said the sector will be restructured through mergers and the provision of a “reasonable” amount of financing. Policies to support the demand for shelter will be implemented differentially, as local conditions dictate.

While the real estate market may not grow vigorously in 2023, we are unlikely to witness the same sort of decline in both the demand for and the supply of housing that we have seen this year. At a minimum, the sector will be much less of a drag on growth.

The CEWC said that domestic investment should focus on accelerating the completion of major projects outlined in the 14th Five-Year Plan. It also emphasized that China needs to make a greater effort to attract foreign investment. In particular, it pointed to the potential for foreign capital to modernize China’s service industry.

The CEWC emphasized that “stability” will be the watchword for 2023 and that policy would be oriented to making progress while maintaining stability. But stability should not be confused with stasis. I expect that we will see a lot of creative destruction. Numerous firms will go bankrupt and new ones will enter the marketplace. This will be a painful process for many but the hope is that, in 2023, the economy will emerge stronger and more vibrant than ever.