Major Economic Challenges Colour the October Data

Major Economic Challenges Colour the October Data(Yicai Global) Nov. 17 -- On November 15, China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) its key economic indicators for October. The data, which showed that the recovery lost momentum, were disappointing. However, the recent fine-tuning of the Zero-Covid and real estate-finance policies could support the economy in the fourth quarter.

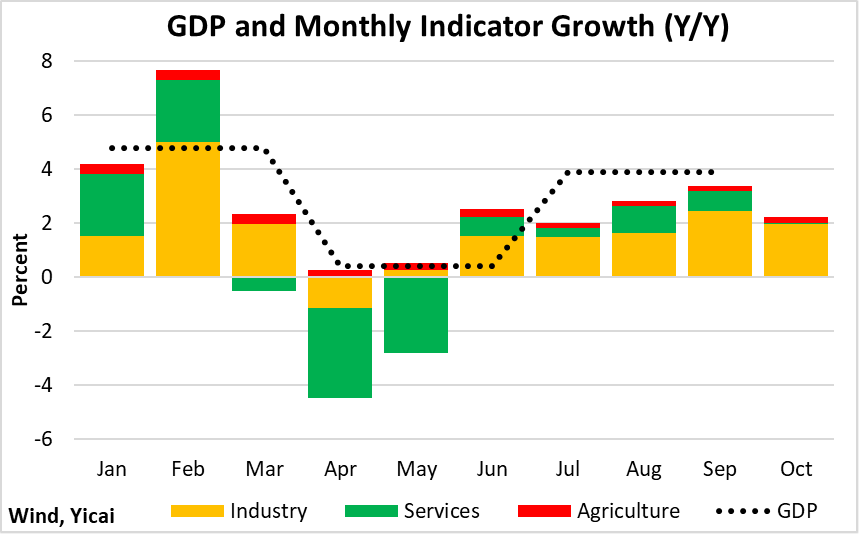

Our monthly GDP indicator combines the NBS’s series for industrial value added and service production with an estimate for the agricultural sector. It suggests that the year-over-year growth of GDP slowed to 2.2 percent in October from 3.4 percent in September (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Concerns about Covid continue to weigh on consumption.

Spending on travel services is typically high in October because of the Golden Week associated with National Day celebrations. This October, only 119 million passenger rail trips were made, down from 248 million in 2021 and well below the pre-pandemic peak of 319 million.

In October, the service sector output was essentially unchanged from a year earlier. Service production growth had been 7 percent before the outbreak of the pandemic. In contrast, the industrial economy remained fairly resilient, growing at 5 percent in October, compared to 6 percent in 2019. However, with private domestic demand fairly weak and external demand slowing, industrial output has been increasingly dependent on public spending.

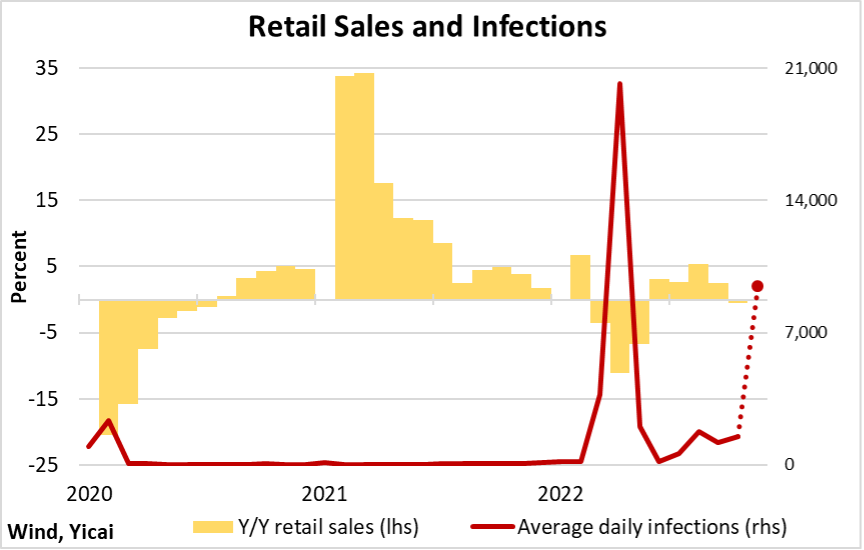

The year-over-year growth in retail sales surprised analysts by falling modestly in October following 2½ percent growth in September. Indeed, retail sales growth seems to be particularly sensitive to increases in new Covid cases (Figure 2). October’s decline in retail sales follows a rise in average daily cases to 1,500 from a recent low of 170 in June. This is the third spike in Covid cases, with retail sales having been disrupted in early 2020 and the spring of 2022 as well.

In the first half of November, average daily new Covid cases exceeded 9,400 and this suggests that consumption will continue to be under pressure.

Figure 2

Chinese policymakers have been trying to balance protecting public health with supporting the economic recovery.

While remaining committed to the Zero Covid policy, they recently made its implementation somewhat less exigent. Quarantine times for inbound travellers were shortened. ”Secondary contacts” of those infected will no longer be traced and isolated. And airlines’ flights will no longer be suspended if infected passengers arrive in China.

It is a sign of policymakers’ confidence that they have liberalized their public health rules even as the number of cases increases. Nevertheless, the extent to which these changes can galvanize consumer confidence remains to be seen.

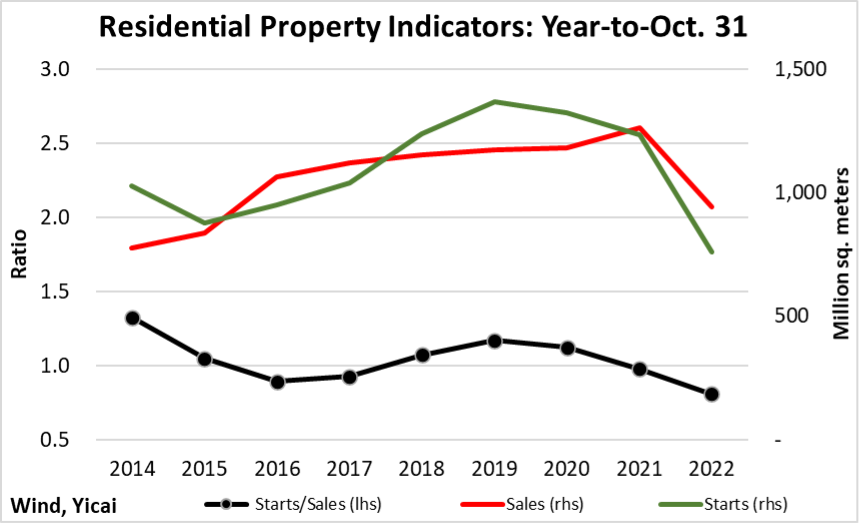

The October data did not show any relief for China’s beleaguered property market.

The volume of new residential floorspace sold remains some 25 percent below last year’s levels, while new homes started are down close to 40 percent (Figure 3). So far this year, the starts-to-sales ratio is only 0.8, while a ratio of 1.0 is normal, on average, over the cycle. This suggests that not enough new housing is being constructed to satisfy the current level of demand.

Figure 3

Developers are not building more, in part, because of the financial constraints they face, which are designed to align the amount they borrow with the health of their balance sheets. Here too, policymakers are being pragmatic. While they continue to be guided by the policy that housing is for living not for speculation, they have encouraged financial institutions to provide to developers by extending or swapping their debts for longer maturities.

To the extent that some of the weakness in housing demand comes from households’ uncertainty about developers’ financial strength and their ability to complete unfinished projects, this policy adjustment could put a floor under the market.

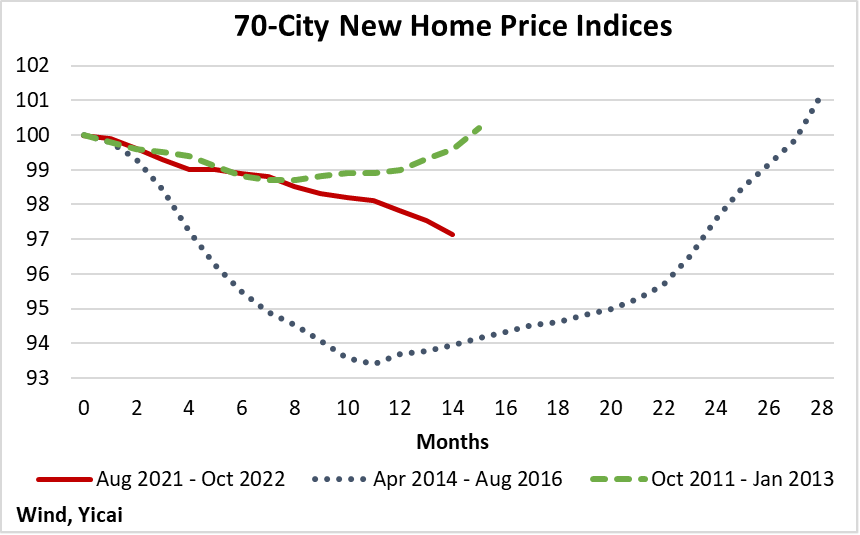

With supply and demand both falling, the rise in inventories has been modest in this cycle. Moreover, new home prices have held up fairly well. Across China’s 70 major cities, new home prices are down only 3 percent from their August 2021 peak. While this is a bigger correction than the cycle in 2011-13, it is not as extreme as what we saw in 2014-16 (Figure 4). A modest inventory build and subdued price pressures suggest that judicious policy changes could be successful at turning the market around.

Figure 4

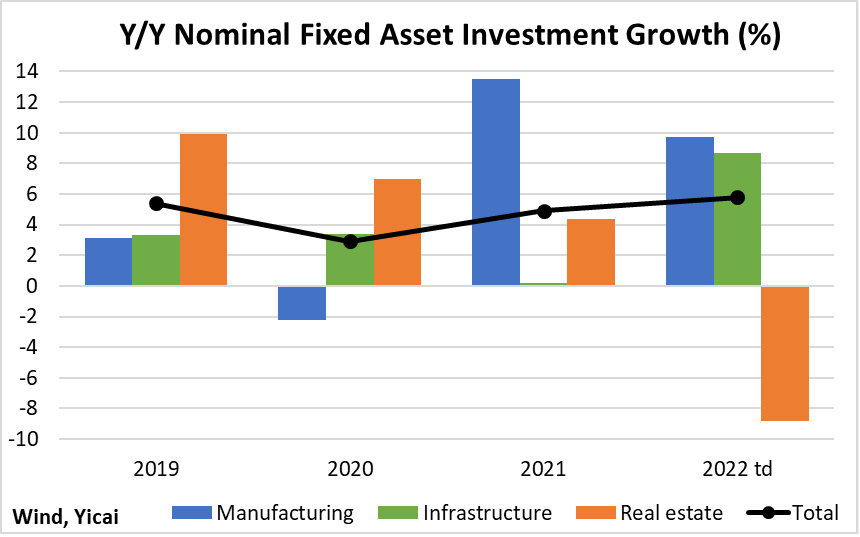

Policymakers have tried to offset the weakness in real estate by spending on infrastructure and encouraging investment in manufacturing (Figure 5). This may make the economy greener and more productive in the future.

Figure 5

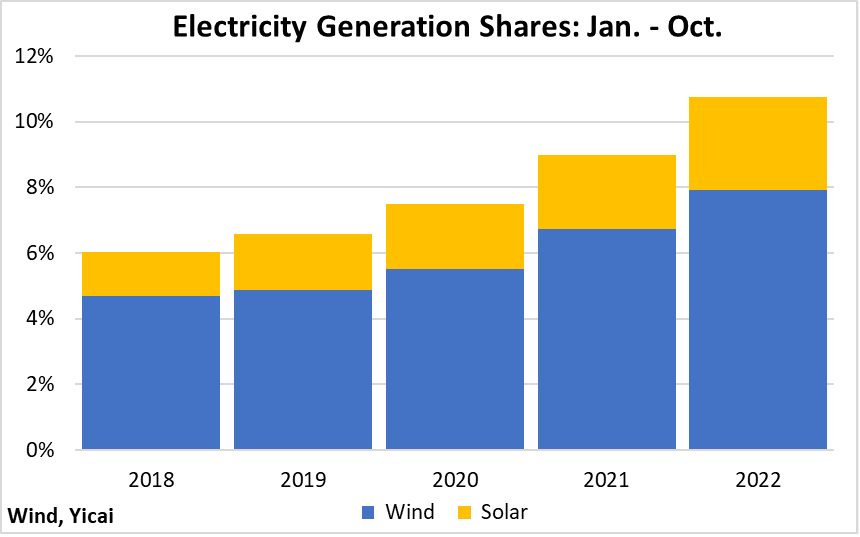

The share of China’s electricity generated by renewable technologies continues to increase. So far this year, China’s electricity production is up 4 percent from 2021. But wind- and solar-generated electricity are up 22 and 30 percent, respectively. As a result, wind and solar accounted for 11 percent of total electricity generation, up from 9 percent in January-October 2021 (Figure 6).

Figure 6

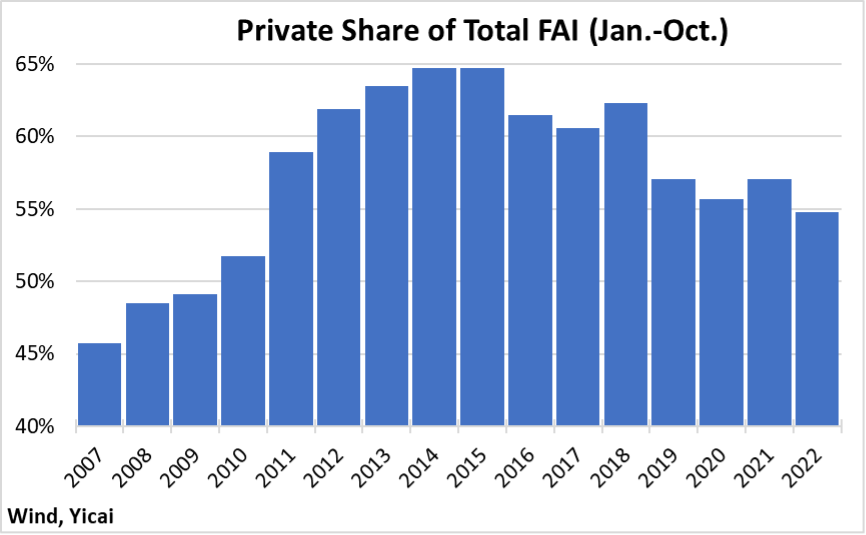

While the growth of fixed asset investment has stabilized, its composition has evolved, with a smaller share accounted for by the private sector. The private sector had accounted for close to two-thirds of fixed asset investment in 2014-15. In the shadow of the trade war with the US, the private sector’s share of fixed asset investment has fallen by 10 percentage points (Figure 7).

Figure 7

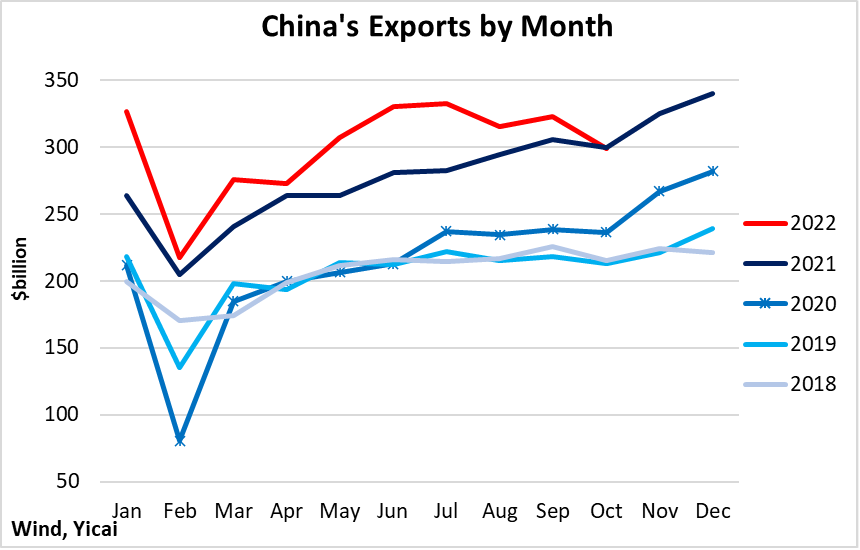

Exports had been a source of strength for the Chinese economy in recent years but that is changing.

The NBS reported that exports grew by 7 percent year-over-year in October. However, looking at exports in CNY terms, as the NBS does, over-states their strength when the currency depreciates. In dollar terms, China’s October exports were flat year-over-year (Figure 8).

Figure 8

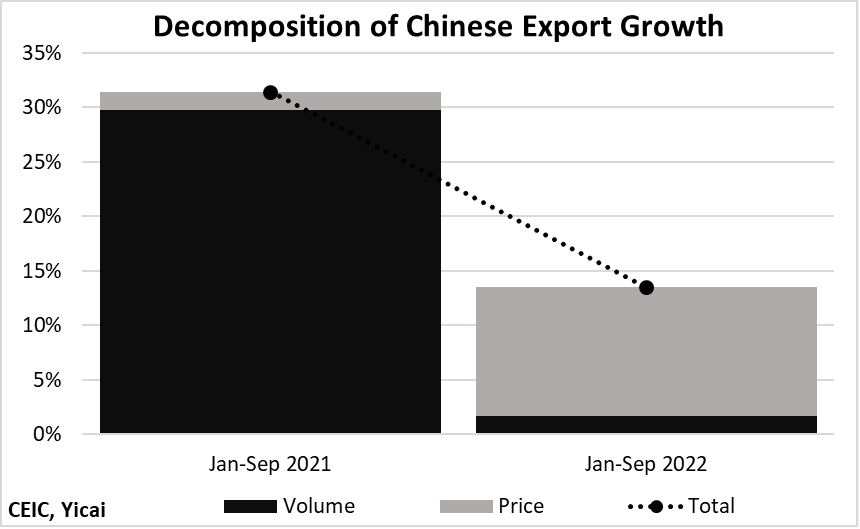

Comparing the first nine months of this year to the same period in 2021, we see a sharp deceleration in export growth. Moreover, there was a dramatic change in the composition of China’s exports. In 2021, almost all of the growth came from greater export volumes. This year, however, most of the growth (in CNY terms) came from higher prices (Figure 9).

Figure 9

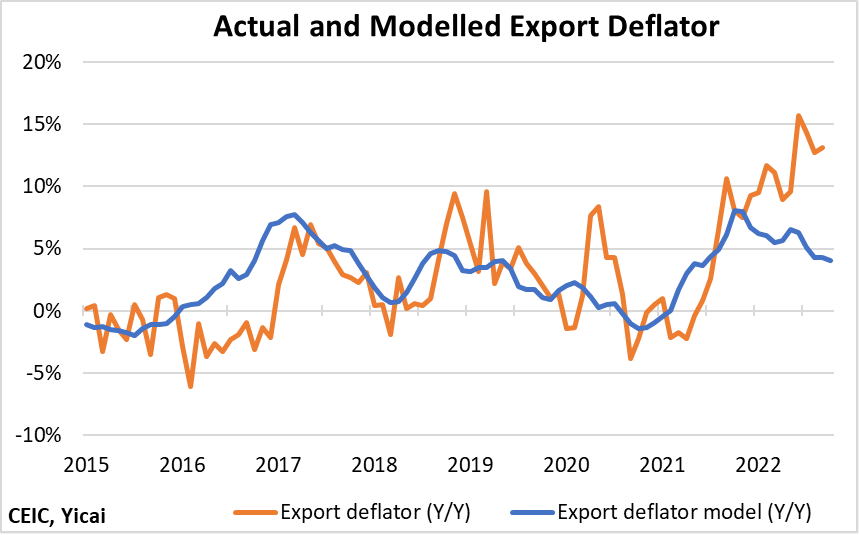

While the export deflator is a volatile series, we find that it can be modelled as a combination of the change in the exchange rate and the growth of Chinese producer prices (Figure 10). For much of this year, export prices have trended above our model’s prediction, posing the risk that they could correct in the near term. Moreover, producer prices have begun to fall and the dollar-CNY exchange rate appears to have peaked. Thus, our model is likely to predict even lower export price growth to the end of the year.

Figure 10

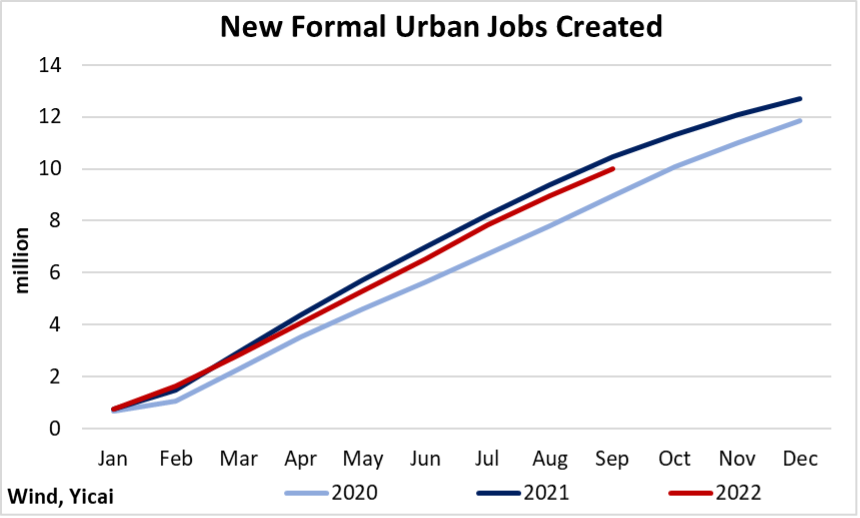

Despite slowing GDP growth, the Chinese labour market is holding its own. It is likely that the 11 million new urban jobs targeted by the authorities were created in the-year-to-October (Figure 11).

Figure 11

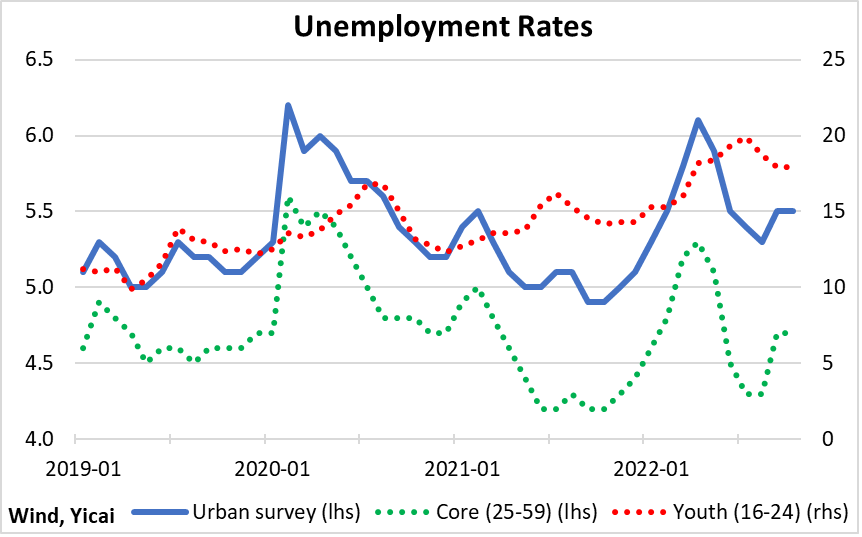

Moreover, the headline unemployment rate is only slightly above pre-pandemic levels due to an increase in new graduates that has swollen youth unemployment (Figure 12),

Figure 12

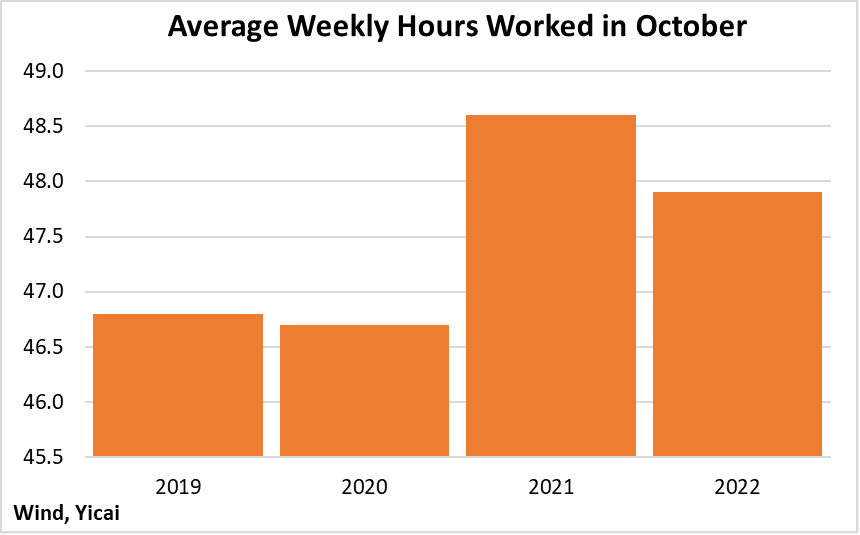

Meanwhile, the average weekly hours worked ticked down in October from their reading a year ago. Nevertheless, at 47.9, they remain relatively high compared to what was recorded in 2019-20 (Figure 13). This means that, even though GDP growth is slowing, there is more than enough work to keep existing employees busy. Elevated hours worked suggest that firms could increase their staffing more aggressively as the uncertainty over the economy’s prospects fades.

Figure 13

Between an increase in Covid cases, a less supportive external sector and a still moribund housing market, the Chinese economy faces prodigious headwinds. I would expect additional policy fine-tuning if growth does not pick up during the last two months of the quarter.