Is the US Chip Export Ban Consistent With Its WTO Commitments?

Is the US Chip Export Ban Consistent With Its WTO Commitments?(Yicai Global) Nov. 11 -- These are tough times for those of us who believe in the value of the rules-based global trading system.

Seventy-five years ago, countries came together to sign the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). The GATT set out the key principles for open and fair trade: most-favoured-nation treatment (all of one’s trading partners have equal standing) and national treatment (no discrimination against foreign products in favour of those produced domestically).

In 1995, the GATT was incorporated into the World Trade Organization (WTO), which currently has 160 members representing 98 percent of world trade.

The WTO’s goal is to ensure that international trade flows as smoothly, predictably and freely as possible. The WTO has been an important component of the “global commons” – the institutional infrastructure that helps minimize international frictions. Indeed, the predictability offered by the WTO was instrumental in supporting the tremendous growth in international trade and the associated increase in global living standards.

Given these achievements, it is disturbing that the US believes that the WTO is no longer fit for purpose. The US contends that China routinely violates its WTO obligations and that the WTO can no longer police China’s behaviour.

But was the rules-based trading system really so badly broken?

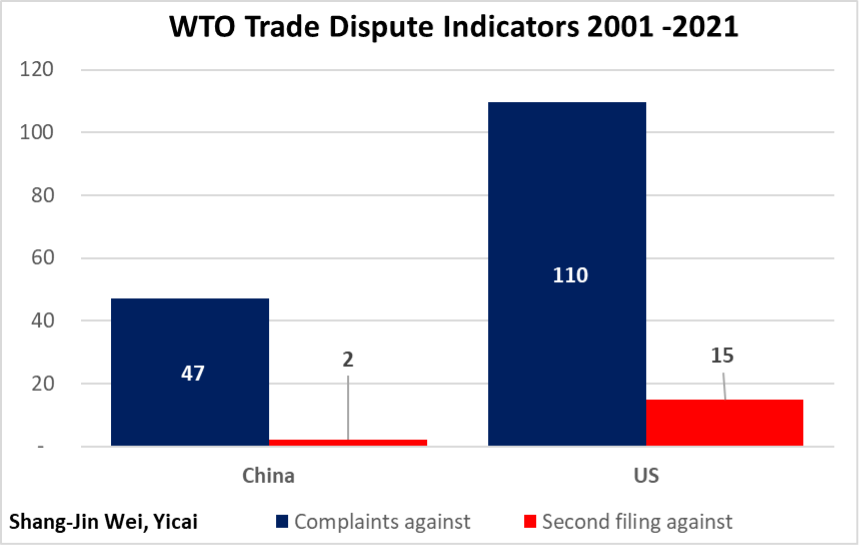

According to data collected by Shang-Jin Wei, a professor of finance and economics at Columbia University, China’s record of compliance with WTO decisions is broadly comparable to those of other member countries (Figure 1).

Between 2001 and 2021, 47 complaints were lodged in the WTO against China’s trading practices. The complaints filed against China accounted for 12 percent of all WTO dispute cases during those two decades.

Over the same period, there were 110 complaints lodged against the US – 28 percent of the total and more than twice as many complaints as against China. According to Professor Wei, China was regarded by the other WTO member-countries as only half as likely as the US to have violated its WTO commitments.

In addition, China had a reasonable record of modifying its policies when a WTO dispute settlement panel ruled against it. Professor Wei notes that one indication of non-compliance is the need for the original complainants to file a second WTO case against the country on the same, or a very similar, issue. Out of the 47 cases against China, only two required a second filing (4 percent). In contrast, there were 15 second-time filings against the US (14 percent).

These data do not support the contention that China was an egregious violator of its WTO commitments and that its trading practices were unchecked by the WTO’s processes.

Figure 1

The WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism was designed to allow for the appeal of unfavourable panel rulings. However, during the Trump Administration, the US refused to agree to the appointment of new members to the WTO’s Appellate Body as existing members’ terms expired.

This breakdown of the WTO’s dispute settlement procedure has had adverse consequences for China. In September 2020, a WTO panel ruled that the tariffs the US imposed on Chinese imports in 2018 and 2019 were inconsistent with its WTO obligations. In October 2020, the US appealed the panel’s decision. As the WTO’s Appellate Body lacks a quorum of members – and therefore cannot hear appeals – there is no longer a way to resolve the dispute within the WTO. Thus, the US’s decision to appeal was not designed to resolve this case. Rather it was a cynical move which put the status of its tariffs into legal limbo.

Even though the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism is in disarray, it still may be instructive to think through whether or not the US’s recent ban on the export of high-performance computer chips to China is consistent with WTO principles.

On October 7, the US Commerce Department’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) announced new rules designed to restrict China’s ability to obtain advanced computing chips, develop and maintain supercomputers and manufacture advanced semiconductors.

The BIS’s rules prohibit companies anywhere in the world from selling high-performance chips to China if they were made using American tools or components. The rules also make it difficult for China to produce its own high-end chips. They prohibit the manufacture of Chinese-designed chips worldwide if the designers used American software. And they prohibit the sales of American-made chip-making equipment or components to China.

The BIS justified its rules by saying that they were necessary to protect the US’s national security and foreign policy interests. No mention was made of any unfair Chinese trade practices.

In general, the GATT’s Article 11, which was adopted by the WTO, prohibits the imposition of non-tariff export restrictions. There are, however, exceptions. One of these is the “national security exception” which is the subject of Article 21.

In particular, Article 21 permits countries to take actions which they consider necessary for the protection of their essential security interests with respect to (i) fissionable materials, (ii) traffic in arms, ammunition and implements of war and (iii) actions taken in time of war or other emergencies in international relations.

Chips are not fissionable material. While the BIS claims that high-performance chips can be used in advanced military systems, including weapons of mass destruction, they are a general-purpose technology rather than arms or ammunition. Indeed, according to the Boston Consulting Group, the US Department of Defense accounts for just 1 percent of the US chip industry’s revenue.

Thus, for the US to justify its actions under WTO rules, it would have to argue that it was already at war with China. While this would be a bizarre line of reasoning, consider that the US’s lawyers justified the 2018-19 tariffs by arguing that Chinese trading practices violated American public morals. Unsurprisingly, the WTO panel did not accept this line of reasoning.

Of course, China is unlikely to receive any meaningful satisfaction from a future WTO panel ruling that the US’s chip export ban is inconsistent with its obligations. That’s because the US can, once again, appeal an unfavourable ruling into oblivion.

US disdain for the WTO has undermined three-quarters of a century of rules-based trade policy. In addition, the chip export ban threatens to reduce the speed of global innovation and the improvement of living standards. The BIS’s rules are designed to prevent China from reaching the technological frontier for chips, supercomputers and artificial intelligence. However, with the Chinese market closed, international firms will have less revenue to support research and development. Their ability to develop better technologies will suffer as a result of this lose-lose policy.

Industry experts argue that China may be able to manage the BIS’s actions in the near term. Last year’s chip shortage has turned into a surplus as the demand for personal computers has fallen.

Moreover, major international firms have received waivers that will allow them to continue operating their factories in China for the next year. Over the medium term, however, China and the global chip industry will need to find creative solutions to these trade restrictions.