Is China’s Investment Really That Unproductive?

Is China’s Investment Really That Unproductive?(Yicai Global) July 30 -- Michael Pettis, a professor of Finance at Peking University recently posted an essay on the Carnegie Endowment for Peace’s website in which he takes exception to the use of the Cobb-Douglas production function to analyse the Chinese economy. The Cobb-Douglas framework for the analysis of an economy’s supply side has a venerable history. Charles Cobb and Paul Douglas published their “A Theory of Production” in the American Economic Review back in 1928. The Cobb-Douglas production function has been around so long because it is intuitive. It models GDP growth as a weighted average of the growth of the capital stock and the growth of labour plus the growth of total factor productivity (TFP). The great weakness of this framework is that TFP growth – the most important factor in an economy’s long-term development – is calculated as a residual: GDP growth minus the capital contribution minus the labour contribution.

Professor Pettis makes it clear that he has no problem with the Cobb-Douglas approach in general. However, he objects to using it to understand China’s growth. He says, “Most economists agree that China suffers substantially more from nonproductive investment than other countries do, and because this investment is not written down to the extent that bad investment is recorded in other countries, it should follow that China’s GDP data is not comparable to that of other countries.”

I disagree with Professor Pettis on both of his key points. I do not believe that there has been excessive unproductive investment in China, and I think that China’s GDP data are broadly comparable to those of other countries. My disagreement with Professor Pettis on the first point is empirical. On the second, we disagree on the fundamentals of national income accounting.

Let’s start with the second point first. Corporate and national income accounting differ in their treatment of investment. Investment is typically an expenditure on a long-lived productive asset. Corporations usually amortize the purchase of a productive asset over a number of years, reducing their profit by a fraction of the asset’s cost in each year until it is fully amortized. Should the corporation realize that the asset was no longer useful and decide to write it off, then it would expense its unamortized value in the year the decision was made and reduce profits commensurately.

National income accounting does not work this way. In the calculation of GDP, the full cost of the asset is recorded in the investment account in the year in which it was acquired. There is no need to make adjustments in subsequent years should the asset become non-productive. That’s because the National Accounts have already recorded its full cost. To make a subsequent adjustment to investment or GDP would be redundant. It would amount to paying for the asset twice. Indeed, I know of no country in which GDP is adjusted for the productivity of its capital stock.

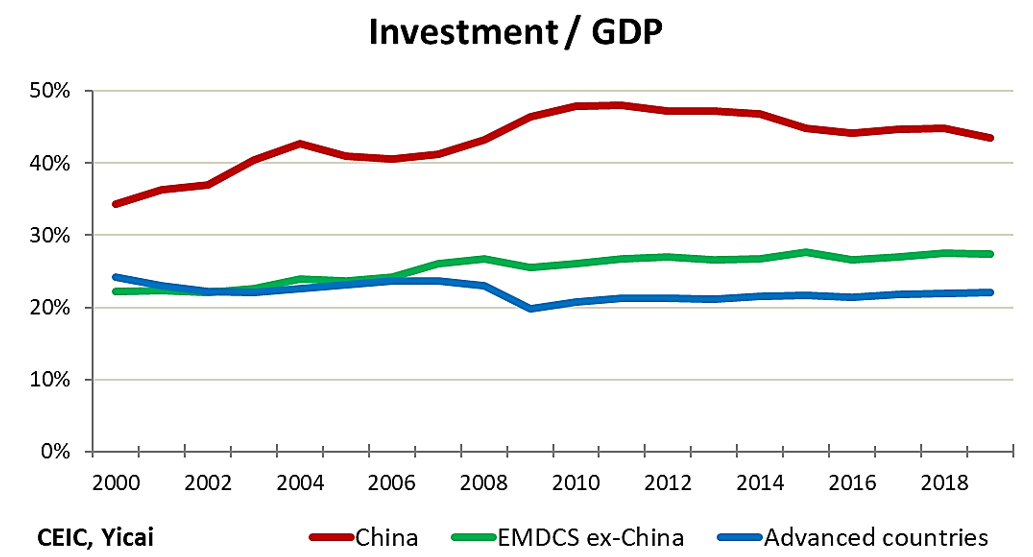

Now let’s consider if Chinese investment has really been so unproductive. China unquestionably invests much more than most other countries. This has been the case since the early 1980s, but the gap widened since 2000. Between 2000 and 2018, the ratio of investment to GDP was 43 percent in China, compared to 22 percent for advanced countries and 25 percent for emerging market and developing countries (EMDCs) ex-China.

With China’s investment rate about double of what we see elsewhere, it has been a common assumption that the efficiency of Chinese investment must be pretty low and that many projects must be non-productive. Indeed, we have observed pockets of over-capacity in certain industries such as steel and solar panels and in certain regions, like Ordos, Inner Mongolia (which is actually no longer a ghost town). However, these are examples of micro-economic imbalances. The macro-economic data tell a very different story.

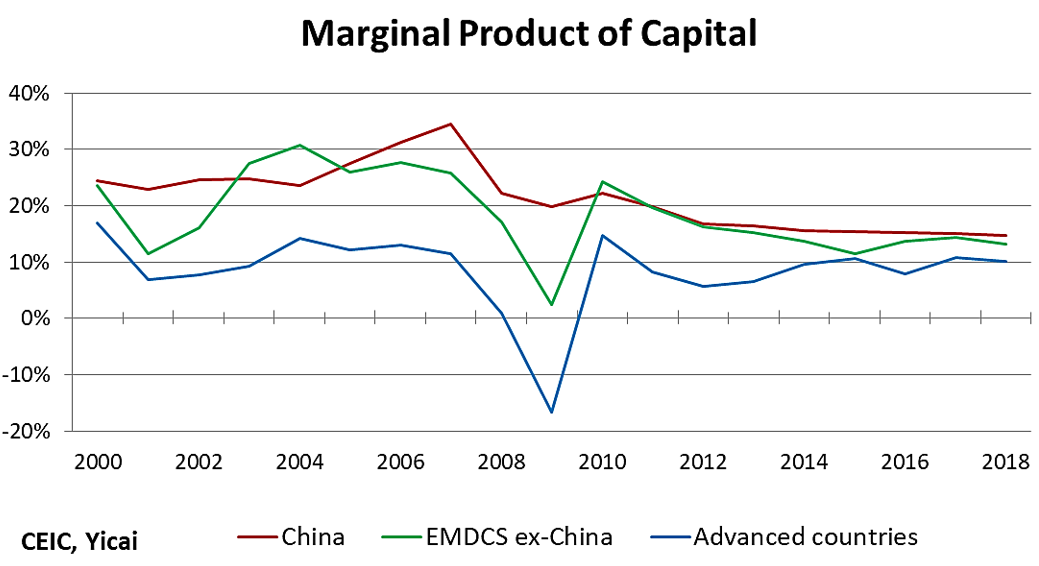

Unproductive investment should have low returns. However, in China’s case, despite the very high investment rates, the marginal product of capital has been very high. The marginal product of capital is the amount of additional GDP that can be generated by a unit increase in capital. It can be calculated as a country’s real GDP growth rate divided by the ratio of investment to GDP.

The graph below presents the marginal product of capital for China, EMDCs ex-China and advanced countries. It shows that China’s marginal product of capital has fallen from 25 percent in the early 2000s to 14 percent more recently. Nevertheless, it remains superior to those of other countries. This suggests that, from a macroeconomic perspective, Chinese investment is relatively productive.

The question of over investment is an important one and one which interests me deeply. While Professor Pettis states that “… a large and rising share of economic activity in the country consists of nonproductive investment,” he does not provide an estimate of how big the problem might be. Different approaches have been used in the literature to assess this question. My colleagues and I used sophisticated filtering techniques to determine the extent to which excessive credit growth led to over-investment in China between 1997-2015. We found over-investment peaked in 2014, when it accounted for about 1.5 percent of GDP or about 3.3 percent of total investment. GDP growth in 2014 was 7.4 percent.

What would it mean, in the context of the Cobb-Douglas production function, if a fraction of investment spending was not productive?

Since it does not result in the creation of productive assets, non-productive investment spending would resemble the purchase of consumption goods. Like a fine meal, they would be consumed and have no effect on the capital stock. Nevertheless, the amount of spending in the economy in that period would be the same. It’s just that its composition would change, with GDP being composed of more consumption and fewer investment goods.

In the current year, with the same amount of GDP being produced by an unchanged quantity of labour and a smaller capital stock, the Cobb-Douglas production function would suggest that TFP growth increased. Over time, however, the misallocation of resources resulting from unproductive investment would result in a fall in both measured GDP growth and TFP.