Is China Decapitalizing Its Banks?

Is China Decapitalizing Its Banks?(Yicai Global) June 24 -- Last week, the State Council’s Executive, that it was encouraging banks to transfer up to CNY1.5 trillion of their profits to the real economy. In particular, banks should lower interest rates, reduce fees and allow small- and medium-sized enterprises to defer their payments.

The China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission that the banks were already actively helping out in the first quarter. They rolled over CNY577 billion in loans, mostly to small- and medium-sized enterprises. In addition, they allowed the deferral of principal and interest payments on CNY880 billion worth of loans. This CNY1.457 trillion represents 1.1 percent of the stock of outstanding commercial bank loans. Reported non-performing loans totalled CNY2.6 trillion in the quarter, following the disposal of CNY450 billion in bad credits. The commercial banks have loan-loss provisions of CNY4.8 trillion, more than enough to cover both the stock of bad loans and the credits treated leniently in the first quarter.

In terms of economic stimulus, CNY1.5 trillion (USD 214 billion) is large, representing 1.4 percent of GDP. Headline fiscal support, measured as the change of the National Deficit, is only about 1 percent of GDP and we estimate broader fiscal support at 3.7 percent of GDP. Thus, banks are being asked to make a significant contribution to the recovery.

There are two reasons for this. First, by encouraging forbearance, the government seeks to avoid a cascade of negative events precipitated by the calling of a loan. Second, the Chinese banking system, generates a tremendous amount of profits.

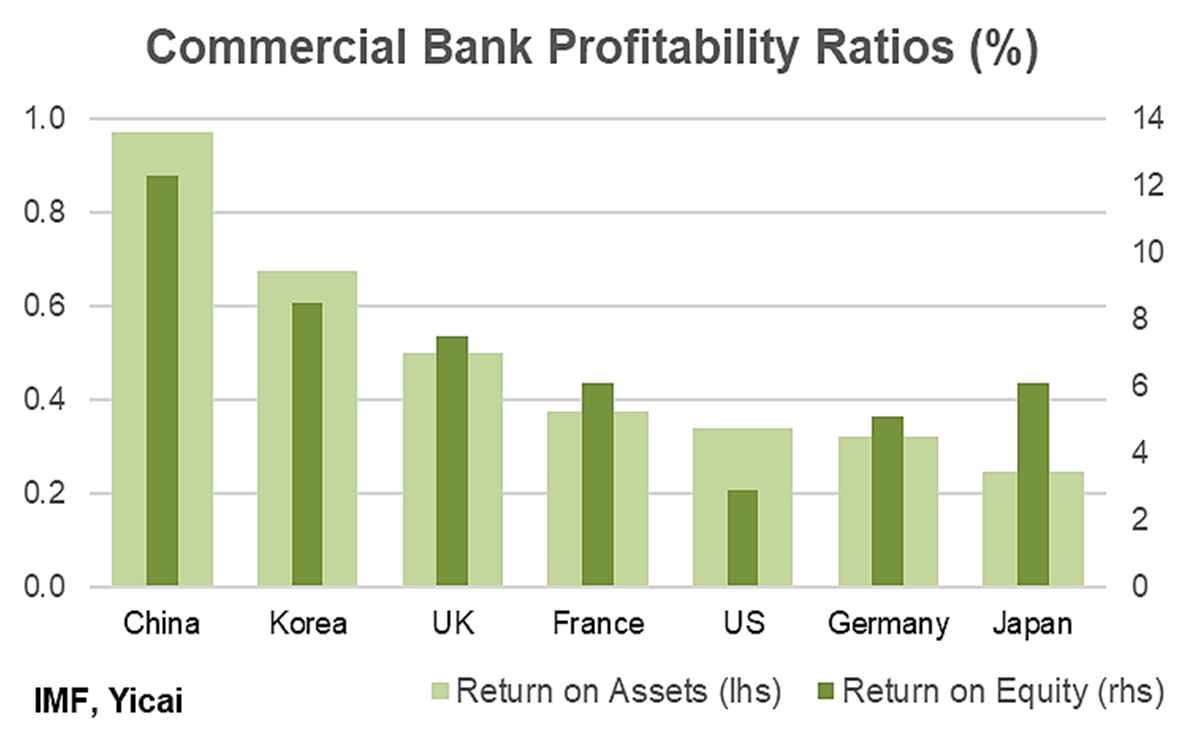

The Chinese banking system is not only the biggest in the world, it is also among the world’s most profitable. The graph below presents profitability data taken from the IMF’s Financial Soundness Indicators. Compared to other countries with large banking systems, China ranks first in both return on assets and return on equity.

Chinese banks are profitable, in part, because they make very large loans. This significantly reduces their per unit overhead costs. According to the IMF data, Chinese banks’ non-interest expenses were only 29 percent of gross income. Among the competitors shown in the graph below, this ratio ranged between 60 percent for the US to 91 percent for Korea. Moreover, according to the , a considerable part of Chinese banks’ loans is to large state-owned enterprises and local government financing vehicles. These exposures have hidden guarantees, which mitigate risk, lower management costs and inflate profits.

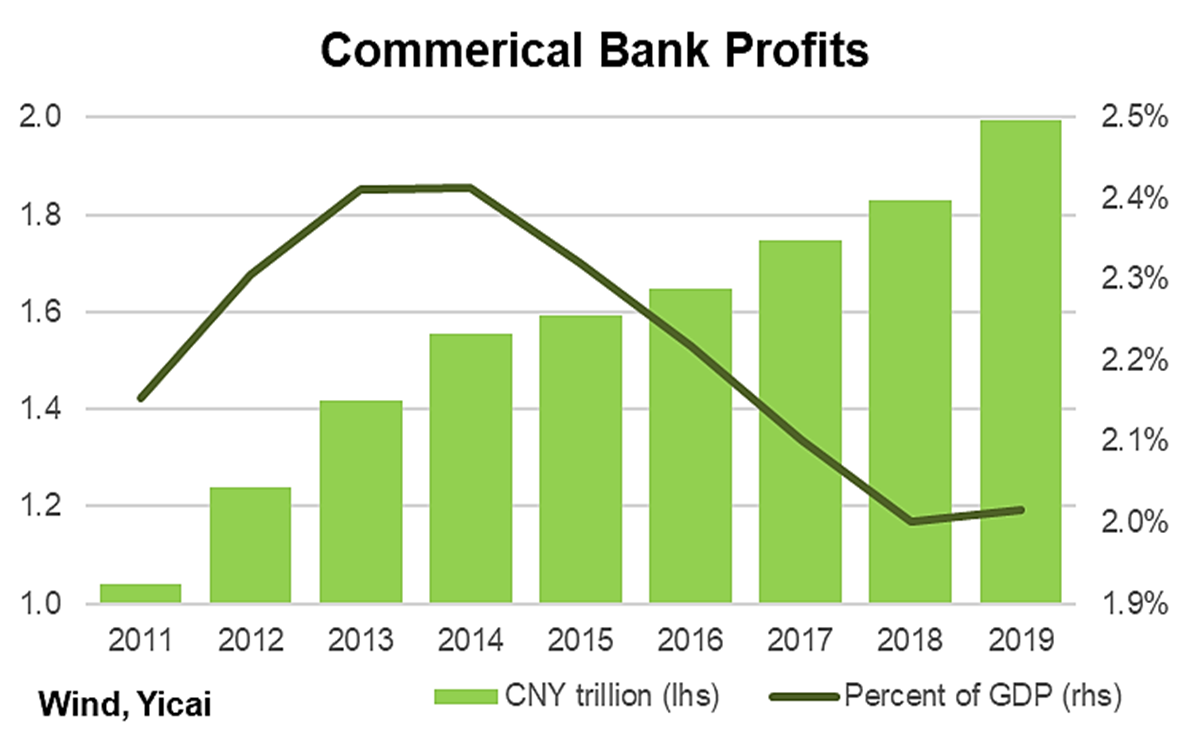

In 2019, commercial bank profits were close to CNY2 trillion. Thus, the State Council’s plan to transfer CNY1.5 trillion to the real economy represents a loss of three-quarters of last year’s profits. The graph below shows that while commercial bank profits essentially doubled between 2011 and 2019, they have fallen, as a share of GDP, since 2014.

Notwithstanding the deep economic dislocation, commercial bank profits were CNY600 billion, in the first quarter of 2020, up 5 percent year-over-year. Nominal GDP fell by 5 percent. As a result, commercial bank profits were close to 3 percent of GDP in Q1.

It is understandable that, in these times of unprecedented uncertainty, the government wants to tap bank profits to support the economy. But, as economists are fond of saying, “there is no free lunch”. In recent years, banks have used 60 percent of their profits to replenish their capital. So, the profit transfer policy will result in a slower buildup of the banks’ capital buffers and will reduce their resilience to shocks.

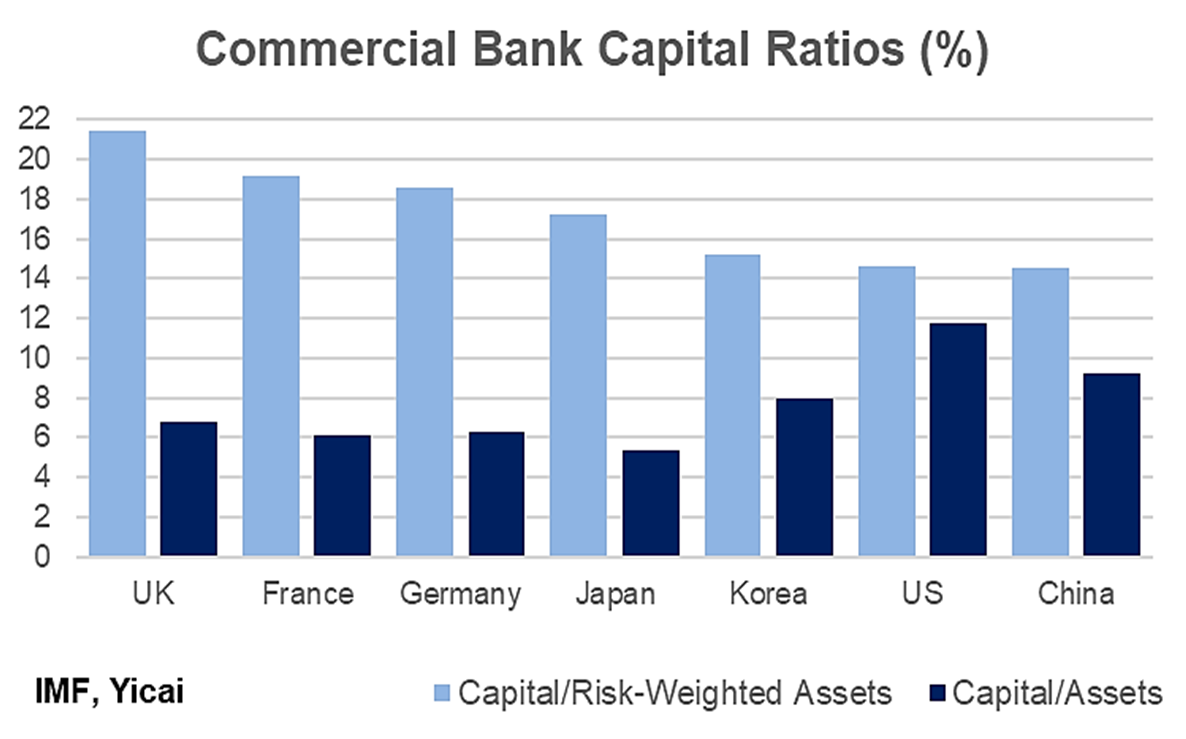

Banks’ resilience is typically measured by their capital to risk-weighted assets ratio. The graph below presents the IMF data for the Chinese banks and their major international competitors. It shows that, at 14.5 percent, Chinese banks’ capital to risk-weighted assets ratio is the lowest in the sample. Nevertheless, the Chinese aggregate ratio is well above regulatory minimums and not far from the US’s 14.7 percent.

The capitalization of Chinese banks appears more favorable when considered in terms of the capital to assets ratio: it Is second highest after the US. In this metric, the assets are not risk-weighted but simply included at book value.

China’s risk-weighted assets are relatively high compared to its book value assets. This is because its share of loans to non-financial corporations, which attract the highest risk weight, is double those of the other countries in the sample. Ironically, the loans to the large state-owned enterprises and local government financing vehicles, referred to above by the People’s Bank, are included with high weights, even though their actual risk might be low.

The analysis above suggests that, while Chinese banks are not poorly capitalized, they will need to find other sources of funding to replace the profits that will be transferred to the real economy.

Recently, the instrument of choice has been the perpetual bond. Perpetual bonds have lower seniority than regular bonds and pay a somewhat higher interest rate. They are cost-effective for the banks, compared to preferred shares, because the interest payment is deductible from their income. Chinese banks only began to issue perpetual bonds last year, using them to raise CNY570 billion in capital. The media that issuance this year to date is five times as high, indicating that Chinese banks are diligently looking for ways to make up for transferred profits.

One of the features of the 2010 Basel III regulatory framework was a countercyclical capital buffer. This buffer is designed to dampen excess credit growth during good times and prevent the supply of credit being constrained by regulatory capital requirements during downturns. While China has not yet formally implemented such a buffer, last week’s announcement by the State Council essentially puts the spirit of the Basel framework into practice.