Is 5 Percent GDP Growth China’s New Normal?

Is 5 Percent GDP Growth China’s New Normal? (Yicai Global) Dec. 31 -- With the new year upon us, China-watchers everywhere are wondering how fast GDP will grow in 2022. Fortunately, the Yicai Research Institute recently surveyed 18 prominent Chinese economists. Their median GDP growth forecast was 5 percent and their range of estimates was fairly narrow, with the most optimistic predicting 5¾ percent and the most pessimistic at 4½ percent. Although it is in line with the 2020-21 average, the economists’ forecast is a full percentage point below 2019’s outturn, and it implies that trend growth has slowed significantly (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The economists see consumption growth below pre-pandemic rates. Fear of contracting Covid and the government’s strict Covid-containment measures will continue to weigh on the service sector. Moreover, the property market slowdown bodes poorly for the purchase of consumer durables and household fixtures.

The economists see investment coming in only slightly weaker in 2022 than in 2019. However, they believe that the composition of investment will continue to evolve with infrastructure rebounding, manufacturing stable and real estate slowing further.

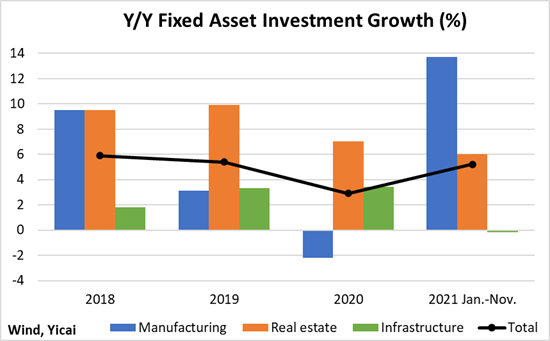

Over 2018-2020, the real estate sector recorded the most rapid investment growth (Figure 2). That changed in 2021. As a result of the government’s “Three Red Lines” framework, which is designed to align property developers’ ability to borrow with the strength of their balance sheets, investment in real estate development slowed sharply throughout the year. The economists expect growth in real estate investment to be negligible in 2022.

Figure 2

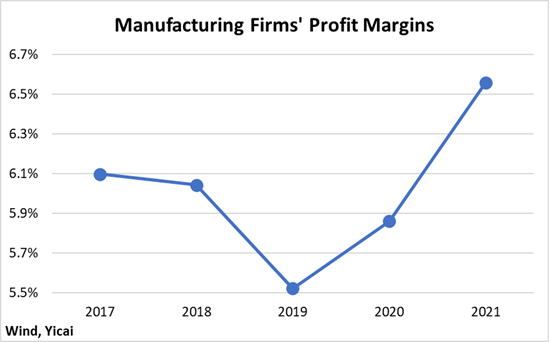

Investment in manufacturing was quite strong in 2021. This has been a pleasant surprise, given the supply chain shortages and power disruptions. While some of the strength of manufacturing investment in 2021 is payback for a weak 2020, it is also consistent with the increasing profitability of the Chinese manufacturing sector. Profit margins in 2021 were significantly higher than over the four previous years (Figure 3). Manufacturing firms have effectively managed the higher input costs stemming from surging commodity prices.

Figure 3

Net exports contributed about 1.5 percentage points to GDP growth in 2021, but the economists see the trade balance as relatively stable in 2022, suggesting a much smaller contribution. They may be too pessimistic. Inventories remain low in the US and Europe and restocking demand could continue to support robust Chinese exports over the first half of the year.

The economists expect monetary policy to remain stable, with the growth of M2 and total social financing in line with the rates recorded in 2021. A majority believe that the People’s Bank of China will hold the one-year loan prime rate steady at 3.80 percent to the end of 2022 (it cut the rate by 5 basis points at its December 2021 meeting). A minority expect further decreases in 2022, with the most dovish seeing the rate falling to 3.55 percent by year-end.

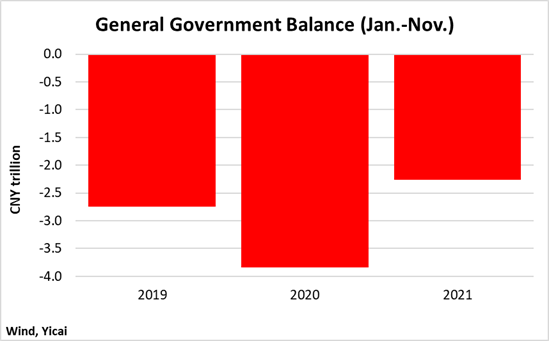

The economists see a role for fiscal policy to support the economy in 2022. The data through November 2021 show that fiscal policy has been a significant drag on growth. As a result of stronger than expected revenue growth, the general government deficit shrunk from CNY 3.8 trillion in 2020 to CNY 2.3 trillion in 2021 (Figure 4). This year’s smaller deficit means that the government is effectively putting less money into the economy than it did last year. At annual rates, this “negative fiscal impulse” represents a drag of 1.7 percent of GDP. Thus, even a neutral fiscal policy in 2022, would be relatively supportive.

Figure 4

Given our assumptions for increases in the labour supply and the capital stock, the economists’ GDP forecast implies a sharp drop in the growth of total factor productivity (TFP). In the five years before the pandemic, annual TFP growth was 2.5 percent. GDP increasing by 5 percent in 2022 would imply TFP growth of only 1.6 percent. And it is this decline in TFP growth that is responsible for lowering trend GDP growth from 6 percent before the pandemic to a “new normal” of 5 percent.

The slowdown in TFP growth highlights the need for further structural reforms to boost productivity. Two intriguing papers published in 2020 examined China’s slowing TFP growth and provided practical policy recommendations for keeping productivity high.

Researchers at the Bank of Japan estimated a model which simulates TFP increases via two channels: (i) the movement of workers from less to more productive sectors and (ii) productivity improvements within the sectors. They extrapolate recent trends to forecast the flow of labour between sectors and they model within-sector TFP increases based on closing China’s productivity gap with the US.

The model fully incorporates the decline in China’s labour supply between 2020 and 2035. Still, based on the experience of other countries, the model suggests that China should be able to grow at an average annual rate of 4.8 percent over the 15-year period. The size of China’s economy would double and the goal set by President Xi would be attained.

The researchers warn that the pace of moving workers out of agriculture (where productivity is the lowest) has been slowing. Moreover, employment has increased in services rather than manufacturing (where productivity is highest). They point out that China’s policy of food self-sufficiency may be impeding the movement of workers out of agriculture. They recommend deepening agricultural reforms, which would allow fewer workers to maintain a high level of food output.

The researchers’ model projects that the value added of China’s manufacturing sector will grow by 1.8 times over the 15 years. In the past, Japan and Korea used export-led strategies that relied on foreign countries to consume their rising manufactured output. However, the researchers believe that China may not be able to adopt this approach, given its already-high share of global manufactures and the current protectionist environment. They worry that China might be “too big to grow.” They think China would be well-advised to boost domestic demand by promoting urbanization since urban incomes are about twice as high as those in rural areas and city-dwellers are much more likely to purchase durable goods.

A recent World Bank Policy Paper also offers prescriptions for maintaining a high rate of productivity growth. Its authors begin by noting the sharp decline in Chinese TFP growth since the Global Financial Crisis. The Crisis appears to have been an inflection point for productivity growth in many advanced and emerging market countries. While external factors may have contributed to the TFP slowdown in China, the authors believe that homegrown factors were also quite important.

They look closely at firm-level data for the Chinese manufacturing sector. Within an industry, the productivity of existing firms actually grew more rapidly after the Crisis (1.0 percent versus 0.8 percent). The problem was with new firms entering the industry. New entrants are typically more productive than existing firms. Before the Crisis, new entrants added 1.3 percentage points to overall TFP growth in the manufacturing sector. After the Crisis, they only added 0.4 percentage points. The policy implication here is that the authorities need to look carefully at barriers to entry that prevent productive firms from entering the market.

The authors emphasize that in advanced countries, the most important source of productivity growth comes from the reallocation of resources from less to more productive firms. However, such resource reallocations have not been important in China either before or after the Crisis. This suggests a potentially important role for mergers and acquisitions in boosting future TFP growth.

The authors cite the common observation that as incomes rise, more is spent on services. Thus, higher-income countries tend to have more employment in the service sector (where productivity is lower) than in industry. With the service share of its economy on the rise, they recommend that China implement policies that raise service sector productivity.

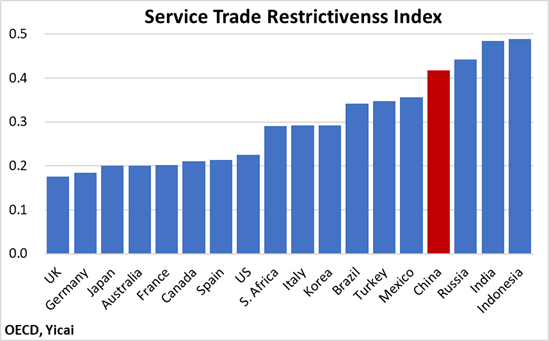

One such measure would be further liberalizing cross-border trade in services. According to the OECD’s restrictiveness index, China’s service trade regime is among the most restrictive in the G20 (Figure 5). While China has liberalized its services trade over time, additional reforms could boost market competition and raise the productivity of the service sector. Indeed, the service sector could benefit from the liberalization resulting from China’s joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

Figure 5

Most China-watchers keenly observe the data flow to assess how GDP growth is evolving and how macroeconomic policy will respond. For those in the financial markets, this perspective is understandable. However, taking a longer-term view, the most important policies are the structural ones. They may have very little impact in the short run, but they can be the ones that influence productivity’s longer-run trend.

One such policy is China’s recent decision to liberalize foreign investment in the automotive industry. Since the mid-1990s, foreign automakers could only produce cars in China by establishing a joint-venture with a local partner. The foreign automaker’s stake in the partnership was capped at 50 percent. Under the new rules, foreign firms can now establish wholly-owned Chinese subsidiaries.

I think it is likely that firms like Volkswagen, Toyota and General Motors will increasingly use China as a platform to export cars. These firms’ Chinese operations will benefit from their parents’ well-known brands and their extensive distribution networks. Moreover, these multinational firms are powerful enough to push back against protectionist trade policies.

China is not a major car exporter. It ranks 16th in the world, between Sweden and Turkey. So, ramping up Chinese auto production and exports appears to be an excellent way to increase high-value-added manufacturing and address the “too big to grow” problem posed by the Bank of Japan’s researchers.