In the Wake of COP26, It’s Time to Reconsider a Carbon Tax

In the Wake of COP26, It’s Time to Reconsider a Carbon Tax(Yicai Global) Nov. 12 -- As the Climate Summit closes, the news out of Glasgow is not good. by the United Nations shows that the emissions reduction pledges made to date – if fully implemented – would likely lead to a 2.2°C rise in global temperatures by the end of the century. , Executive Director of the International Energy Agency, notes that if we account for India’s stronger 2030 targets and its pledge to hit net zero emissions by 2070, global warming could be limited to 1.8°C. In any event, it appears that the goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement – to limit projected global warming to less than 2°C, with an aspirational target of 1.5°C – is slipping beyond reach.

While the world’s failure to commit to a path that would achieve the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C target is disappointing, a more pressing concern is that countries may not even meet their relatively modest commitments. Close to 50 countries and the European Union have pledged to move to net-zero emissions by mid-century. However, the finds that many of these plans are ambiguous and few are backed up with the concrete policies and near-term targets needed to make them credible.

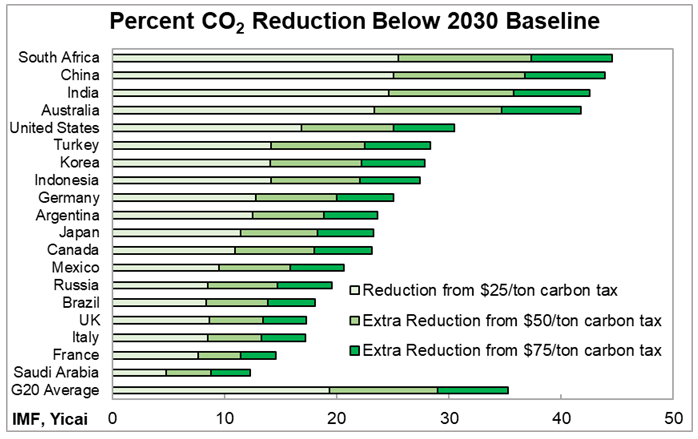

Agreement on imposing a global carbon tax – a charge on the carbon content of fossil fuels – can be a very effective and equitable way to reinforce national plans and ensure that countries’ commitments are met. Indeed, the IMF believes that carbon taxes are the to reduce domestic CO2 emissions. Its modelling suggests that if the G20 were to implement carbon taxes of $25, $50, and $75 per ton, then their CO2 emissions would fall by 19, 29, and 35 percent respectively by 2030 (Figure 1). In contrast, the United Nations estimates that the updates to the national plans submitted to COP26 will only reduce emissions by 7.5 percent compared to the previous round of commitments.

Figure 1

The IMF emphasizes that reducing CO2 emissions will have particularly big health benefits in countries where carbon use is high. Across all G20 countries, it estimates that a $50 carbon tax would prevent 600,000 premature air pollution deaths, of which 60 percent would be in China.

Compared to cap and trade systems and other carbon mitigation schemes, carbon taxes are relatively simple and easy to implement. Moreover, they make full use of the market and afford consumers and producers the greatest freedom in deciding how the needed carbon emissions reductions will be achieved.

Make no mistake about it, reducing CO2 emissions by taxing carbon means that prices will rise and our standard of living will fall. To illustrate, one barrel of oil contains the equivalent of of CO2. Applying a carbon tax of $75 per ton means that the price of a barrel of oil would rise by $32. With oil currently selling for close to $80 per barrel, that’s a 40 percent increase. Since oil and other fossil fuels are used pervasively in the economy, a carbon tax would raise the prices of many widely-used goods and services including home heating, cooking fuels and transportation.

While the point of these higher prices is to encourage households and businesses to economize on carbon-intensive items, the poorest segments of society may find such a jump in the cost of living hard to bear. Indeed, increases in fuel prices sparked the massive protests in and in .

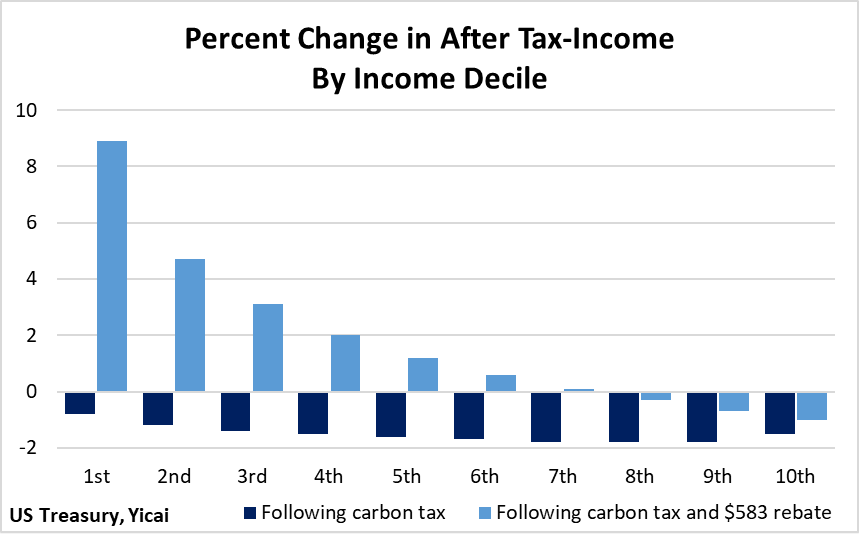

The good news is that governments can use the revenue from the carbon tax to rebate consumers and protect those at the bottom of the income distribution. The model simulations undertaken by the in 2017 demonstrate the power of such rebates. In a first scenario, a carbon tax of $49 per ton is imposed. Prices rise and real incomes fall. For those in the 1st decile (the poorest 10 percent of households), the decline is 0.8 percent (Figure 2). The impacts increase up to the 9th decile, where household income falls by 1.8 percent. For the top decile, the decline is only 1.5 percent.

Figure 2

While the incidence of the carbon tax is progressive over most of the income distribution, policymakers could still worry about its effect on the poor. So, in a second scenario, the carbon tax is fully rebated by giving each person $583. Under this scenario, in which the government returns all of the revenue it received from the carbon tax, the incomes of 70 percent of the households actually increase and only the richest 30 percent are worse off. This simulation shows that careful design can help build a domestic constituency for a carbon tax. It also indicates that a smaller rebate – perhaps only half as large – would leave the bottom 70 percent of the income distribution no worse off after the carbon tax while providing the government with significant resources that it could put into climate change mitigation.

It would be best if all countries adopted a common carbon tax. A common carbon tax would ensure that no country would be at a competitive disadvantage from using a price-based mechanism to reduce CO2 emissions. It would also prevent the offshoring of production to jurisdictions where emissions regulations were relatively lax.

The desire to establish a level playing field with respect to the cost of carbon is what drives economies like the European Union to implement a . Beginning in 2023, the carbon content of iron and steel, cement, fertilizer, aluminium and electricity imported by Europeans will have to be reported. By 2026, these imports will be taxed if the price they paid for the imbedded carbon was lower than Europe’s.

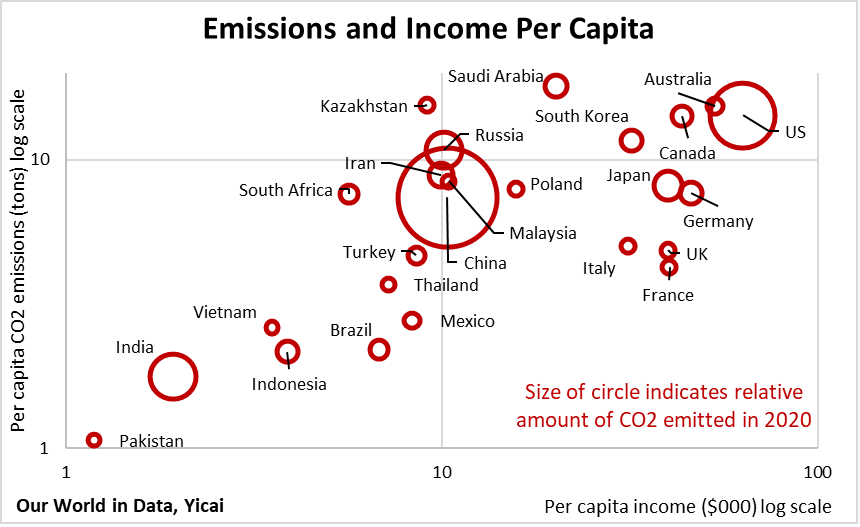

Establishing a global price for carbon runs into the same sort of distributional issues that confront a carbon tax domestically. Looking at the world’s top 25 emitters of CO2, we can see there is a broad tendency for per capita emissions to rise with per capita income (Figure 3). Still, some of these countries are much wealthier than others and can more easily bear the tax. Per capita income in the US, the world’s second-biggest emitter, is about 33 times as high as in India, the third-biggest.

Figure 3

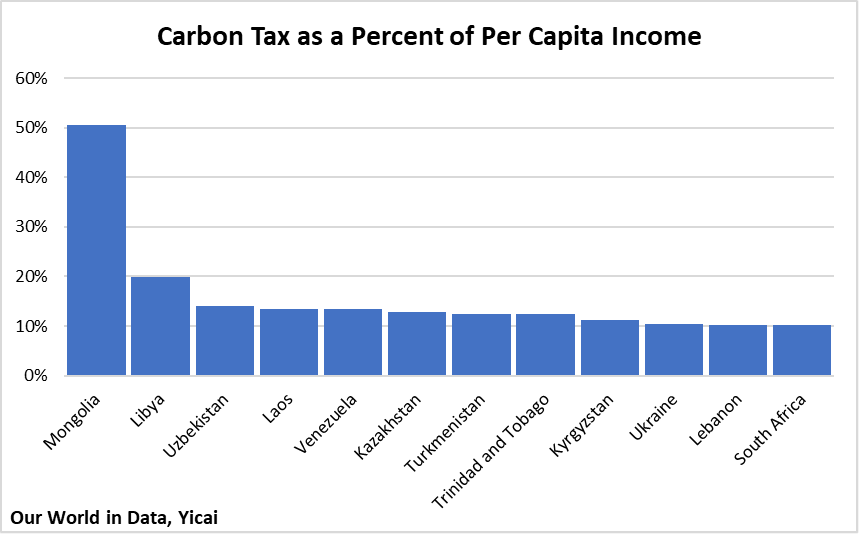

A common carbon price would hit fossil fuel exporting developing countries particularly hard (Figure 4). A $75 carbon tax would eat up half of per capita income in Mongolia, 20 percent in Libya and close to 10 percent in ten additional countries. This compares to just over 1 percent of per capita incomes in rich developed countries.

Figure 4

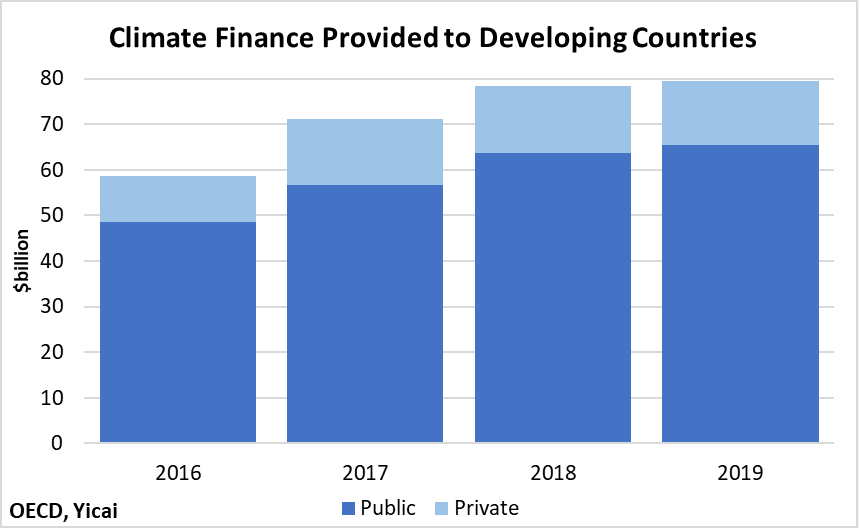

Even in the absence of a common carbon tax, developed countries acknowledged their responsibility to assist developing ones in adapting to climate change. In 2009, developed countries pledged to increase their support to $100 billion per year over the period 2020-25. Data through 2019 show the combined public and private flows amounted to close to (Figure 5). Given the financial stresses the pandemic put on developed countries, it is unlikely that the $100 billion target was reached last year (the OECD will only have the data compiled in 2022).

Figure 5

Even if the pandemic is brought under control soon, it is unlikely that developed countries will feel that their fiscal situations are sound enough to permit them to generously support their developing neighbours’ climate mitigation. However, a carbon tax could give them access to the necessary resources.

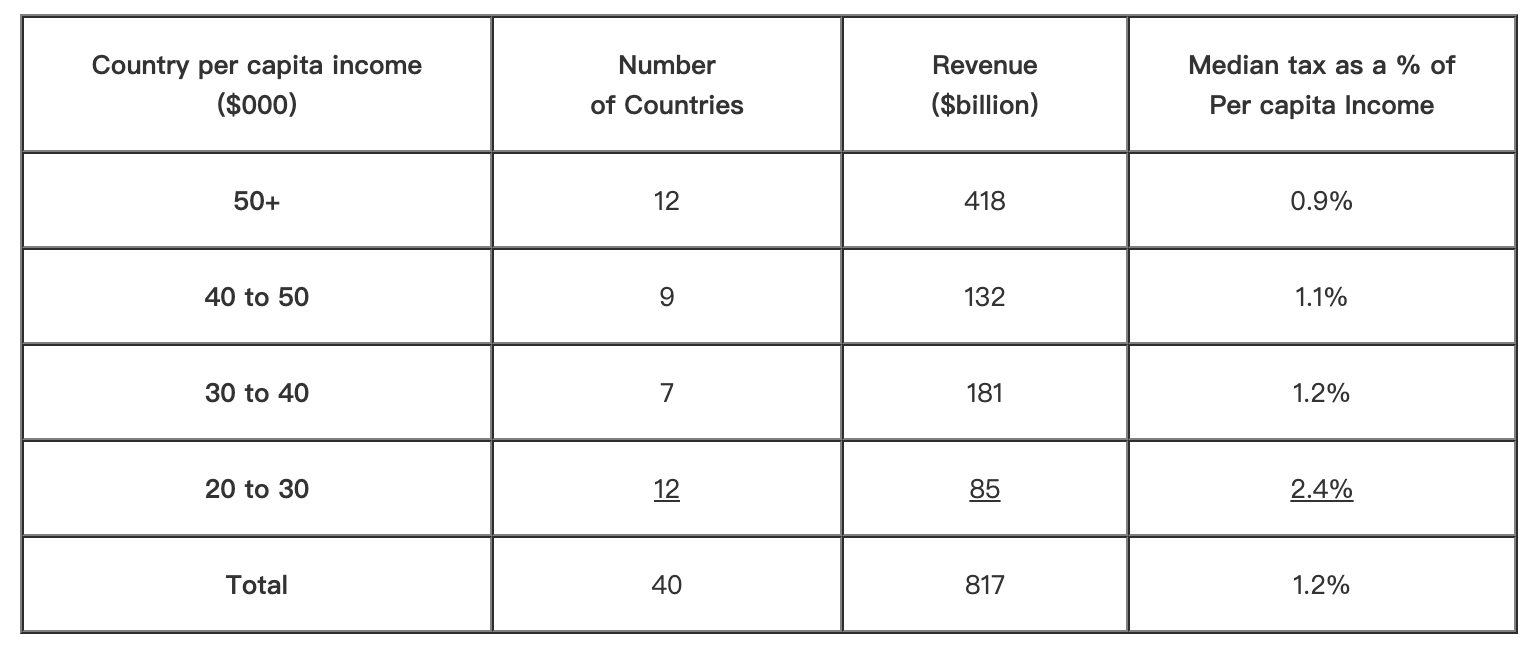

Table 1 makes a simple estimate of potential revenue from a carbon tax by multiplying each country’s emissions by $75. The tax generated by the world’s 40 richest countries – those with per capita incomes in excess of $20,000 – could amount to something like $800 billion per year. This would be more than enough for the developed countries to fulfill their Paris Agreement commitment toward developing countries and to protect the poorest at home.

Table 1:

Estimate of Revenue from $75 Carbon Tax

As the Climate Summit came to a close, China and the US issued a that reaffirmed their commitment to the Paris Agreement’s targets. Moreover, they recognized the “significant gap” between efforts made to date to address climate change and those that are needed to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goals. Most importantly, they intend to close the gap through strengthened and accelerated climate action. We would likely need a new international organization to monitor the implementation of the global price for carbon and the transfer of tax revenues from rich to poor countries. Harvard Professor Kenneth Rogoff has proposed creating a that would transfer and coordinate aid and technical assistance to help developing countries decarbonize. Hopefully, this is an option that the global community can carefully consider following the disappointing COP26 outcome.

A pledge by the world’s two biggest emitters to work together is a ray of hope after a pretty bleak set of meetings in Glasgow. Let us hope that they review the contribution that a global carbon tax can make in avoiding a catastrophic outcome for our planet.