How Strong is Chinese Academic Research?

How Strong is Chinese Academic Research?(Yicai Global) Jan. 7-- China’s labour force is declining. Its investment is constrained by high debt levels. Thus, the growth of China’s economy will increasingly rely on raising productivity. Indeed, President Xi has the key role that innovation must play in China’s future economic development.

Academic research is one channel through which innovative ideas and processes are discovered and disseminated. journal and country rankings allow us to assess the quality of Chinese academic research and how it has evolved over time. Scimago is a publicly available portal, developed by a research group in Spain, that gives us the tools to analyze the academic journal articles contained in the , which is the largest database of peer-reviewed academic literature.

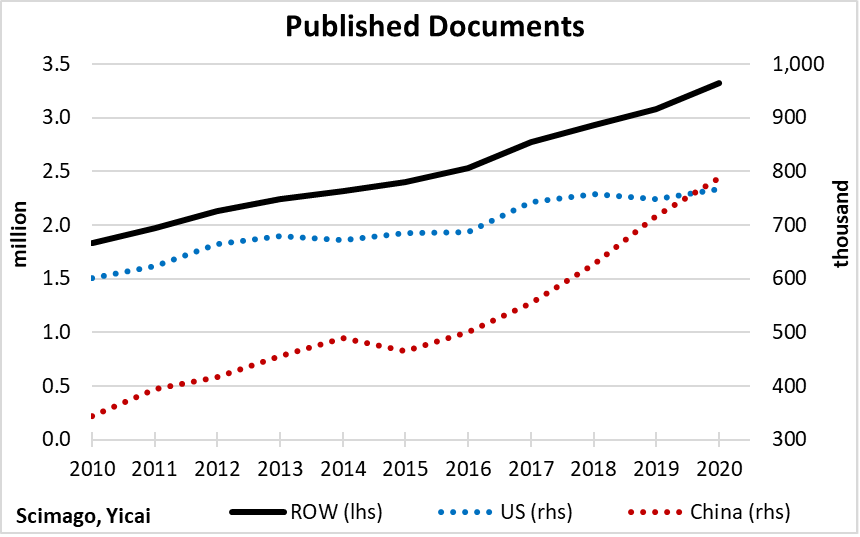

There has been a tremendous increase in academic publications over the last decade. According to Scimago, there were 4.9 million academic documents published in 2020. This is 75 percent more than published in 2010. China’s output rose particularly quickly, up 129 percent in the decade (Figure 1). In fact, China ranked first in the world in 2020, narrowly edging out the US. Each country accounted for roughly 16 percent of the world’s academic output. The US’s publications grew relatively modestly, only rising by 28 percent over the ten years, while those of the rest of the world (ROW) grew by 81 percent.

Figure 1

While the increase in the volume of academic research in China has been dramatic, what can Scimago tell us about its quality?

An often-used measure of an academic paper’s quality is the number of times it has been cited by other papers. A highly-cited paper is clearly influential and can be thought of as presenting high-quality research. Scimago allows us to calculate citations per published document on a country-by-country basis, which we can use as a rough indicator of the quality of national academic output.

It will come as no surprise that the older an article is, the more citations it is likely to have. On average, articles published in 2020 had 1.2 citations. Those published in 2015 averaged 16.7 and those published in 2010 averaged 25.2. Thus, the data needs to be analyzed on a year-by-year basis rather than averaged over time.

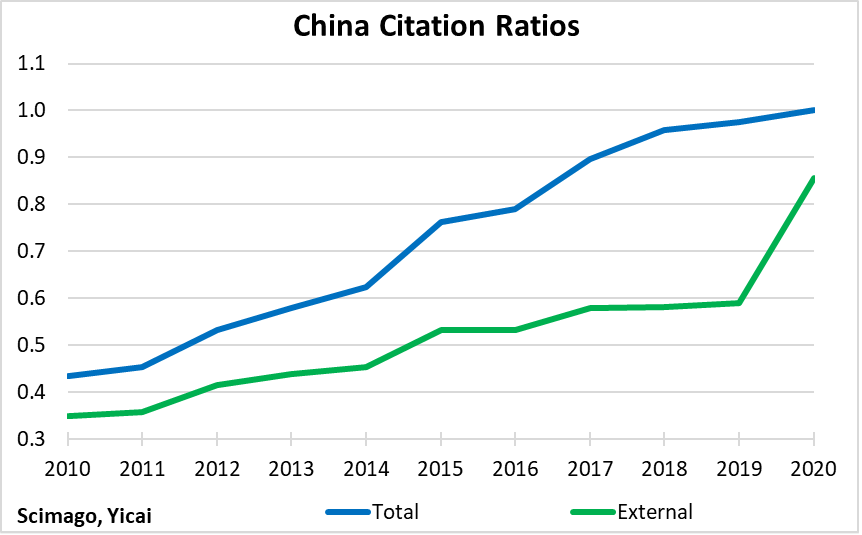

To assess the quality of China’s academic output, we create two ratios. The first is the “total citations ratio” which is China’s citations per document divided by those of the US. A ratio of 1.0 indicates that Chinese and US documents have the same number of citations and are of equal quality.

The second ratio is the “external citations ratio”. Here we exclude “self-citations” which occur when authors cite their previous work. While there are many legitimate reasons for academics to reference their earlier research, the inclusion of self-citations in measuring academic quality is . This is because when citations are used as a measure of quality, there is a strong incentive to inflate one’s citation count. Our “external citation ratio” is calculated as China’s external citations per document divided by those of the US. Again, 1.0 would indicate equal quality.

I should mention that the US does not represent the “gold standard” for the citation-based measure of academic quality. Papers written by Swiss, Danish and Dutch researchers tend to have 25-40 percent more total citations and double the number of external citations compared to those written by Americans.

Both of our citation ratios indicate that the quality of Chinese research is increasing (Figure 2). The total citation ratio increased from 0.43 in 2010 to 1.0 in 2020, suggesting a convergence in China’s quality with that of the US. The external citation ratio initially rose slowly, from 0.35 in 2010 to 0.59 in 2019. But, in 2020, it jumped to 0.86. On this basis, the quality of Chinese research has not yet converged with that of the US, but it’s getting close.

As noted above, recent research tends to have relatively few citations. So, it is possible that the ratios for 2020 could look quite different in a few years, as the research is disseminated more widely. The ratios for future years merit close monitoring.

Figure 2

Most of the papers published by Chinese academics were in the five fields of engineering, medicine, material science, computer science and physics/astronomy. The Scimago portal allows us to calculate citation ratios to assess quality in each one of these subject areas.

Looking at the ratios for 2020, Chinese academics appear to be particularly strong in medical research (Figure 3). Their total and external citation ratios are 1.24 and 1.42, suggesting significantly higher quality than the output of American medical researchers. The relative quality of Chinese research in the remaining four fields does not appear to be as high. The total and external citation ratios average 0.76 and 0.45, respectively.

Figure 3

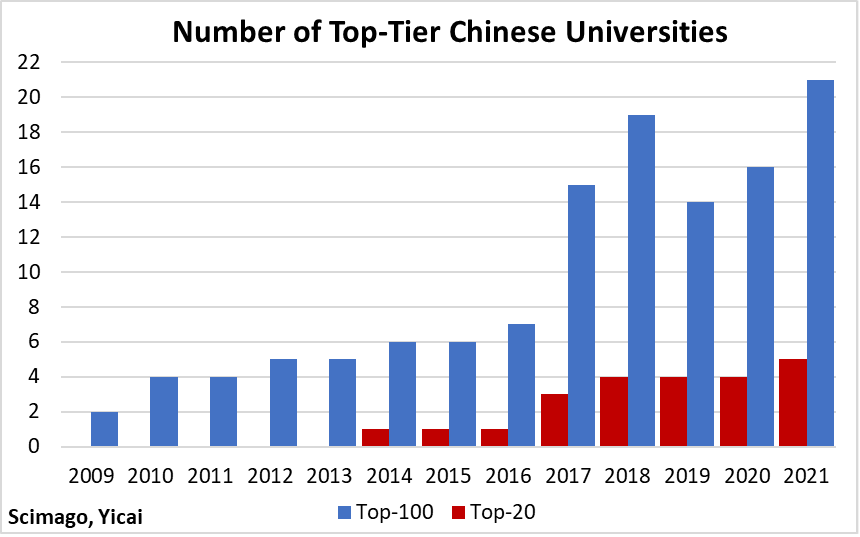

Scimago’s allows us to take another perspective on Chinese academic quality and its evolution over time. To assess a university, Scimago creates an indicator based on the quantity and quality of its research (50 percent), its creation of high-quality patents (30 percent) and the extent of its digital network (20 percent).

The data show that Chinese universities’ quality has risen over time (Figure 4). In 2009, Scimago only ranked two Chinese universities in their top-100: Tsinghua (#43) and Zhejiang (#70). By 2021, the top-100 contained 21 Chinese universities, placing China second to the US with 42 and well ahead of the third-place UK with 7.

A similar story emerges when looking at the top-20 universities. Tsinghua broke into this elite group in 2014. In 2017, it was joined by Peking and Zhejiang. By 2021, Jiaotong and the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences were also in the top-20. China’s five institutions are second to the US’s 11. The UK has three and Canada has one university in the top-20.

In 2021, Scimago ranked Tsinghua as the third-best university in the world, behind Harvard and Harvard Medical School and ahead of Stanford.

Figure 4

The Scimago data indicate that there has been a steady improvement in the quality of China’s academic output, both in terms of how often Chinese academics’ research is cited and how highly its universities are ranked. Moreover, China has achieved academic excellence in medical research and the work undertaken in Tsinghua University. The challenge for policymakers is to broaden these successes and ensure that the upward progress is maintained.