How Much is China’s Property Market Weighing on Its Economy?

How Much is China’s Property Market Weighing on Its Economy?(Yicai) Sept. 8 -- China’s growth this year has been weaker than expected as its economy has been hit by two severe shocks.

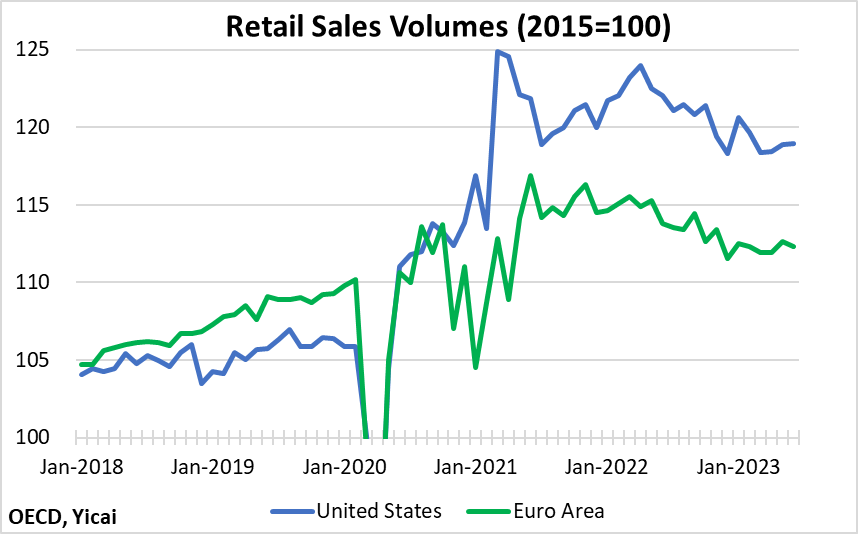

First, tight monetary policy in its trading partners is depressing consumption and, as a result, the demand for China’s exports. Figure 1 shows that the volume of retail sales in the US and the Euro Area has been trending down for the last year and a half.

Figure 1

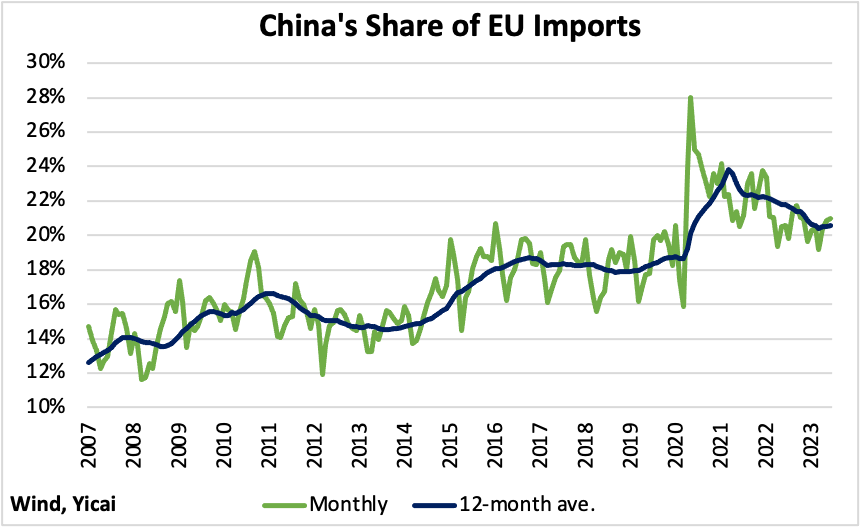

Of course, Chinese exporters are not alone in having to manage these challenging conditions. Those from other countries are in the same boat. However, Chinese firms are holding their own in key markets like the European Union, which has been purchasing 21 percent of its imports from China, up 3 percentage points from pre-Covid levels (Figure 2). These data suggest that there is nothing wrong with China’s export sector and that sales should rebound once foreign demand stabilizes.

Figure 2

Data released by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) allow us to quantify the impact of weaker net exports on China’s GDP growth. The NBS estimates that net exports subtracted 0.6 percentage points from growth in the first half of the year. In other words, if monetary policy in China’s trading partners had been neutral, China’s GDP growth would have been 6.1 percent instead of the 5.5 percent actually recorded.

The second shock from which the Chinese economy is suffering is a domestic one – the downturn in the property market.

To some extent, this shock was policy-induced. In August 2020, the government introduced guidelines to keep the growth of developers’ liabilities in line with the strength of their balance sheets. Subsequently, the pandemic reduced households’ willingness to shop for apartments. This exacerbated developers’ liquidity squeeze, as a large proportion of buyers typically pay for their apartments before they are built. Such pre-sales had provided developers with an important source of funds.

Even though the pandemic is behind us, households remain wary of buying new apartments. They have concerns about developers’ creditworthiness and they are uncomfortable putting their money down in advance. The recent difficulties reported by Country Garden, one of the country’s biggest developers, only serve to heighten households’ wariness.

The NBS does not provide a ready metric to gauge the impact the property market downturn is having on GDP growth. Its data shows that construction plus real estate accounted for 13 percent of GDP last year. This is a rough estimate of the sector’s direct importance to the economy. However, the property market is deeply intertwined with other sectors. It has upstream linkages to building supplies and downstream linkages to household appliances and home furnishings.

Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang use input-output tables to get a more comprehensive picture of the importance of the real estate sector within the Chinese economy. They find that, considering all the relevant linkages, residential and commercial real estate together account for 24 percent of GDP.

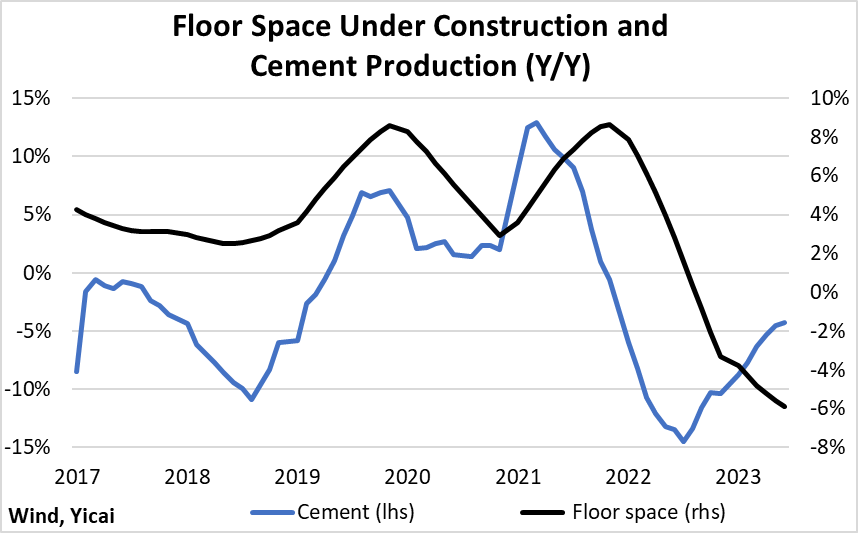

The NBS provides a series of measures of real estate activity including investment, starts, sales and completions. I believe the most comprehensive is its measure of “floor space under construction”. This comprises both residential and commercial construction, with the former accounting for 70 percent of the total. The year-over-year growth rate of the smoothed (12-month moving average) floor space under construction series is shown in Figure 3.

To get a sense of whether or not this series is a meaningful proxy for real estate activity, I compare it to the growth rate of a smoothed version of China’s cement production. Since real estate is a big user of cement, it is not surprising to find a strong correlation between the two series.

Figure 3

In fact, even the gaps between the two series are meaningful.

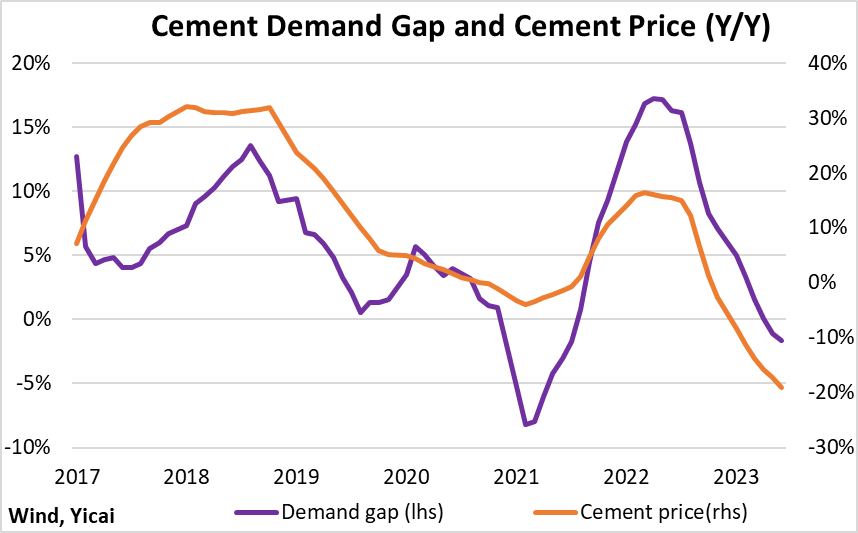

I create a cement demand gap (“Gap” in Figure 4), which is the growth rate of floor space under construction minus the growth of cement production. It turns out that the cement gap is positively correlated with the growth rate of the (smoothed) cement price. When floor space grows faster than cement production (i.e., the gap increases), the cement price rises and vice-versa.

Figure 4

To estimate the impact of the property market downturn on GDP growth, I can simply multiply the growth rate of floorspace under construction by Rogoff and Yang’s estimate of the broad importance of the real estate sector in the Chinese economy, 24 percent.

My calculations suggest that the property market added about three-quarters of a percentage point to GDP growth in 2017-18 (Figure 5). Over the next three years, its contribution doubled. In 2022, the property market only added 0.6 percentage points to what was very weak GDP growth. So far this year, it has subtracted 1.2 percentage points from GDP growth. This implies that, abstracting from the weakness in the property market, the economy grew by 6.7 percent in the first half.

Figure 5

There is also the potential for the property developers’ liquidity problems to affect the health of China’s financial institutions. However, both banks and trust companies have managed down the financial stability risks associated with the property developers.

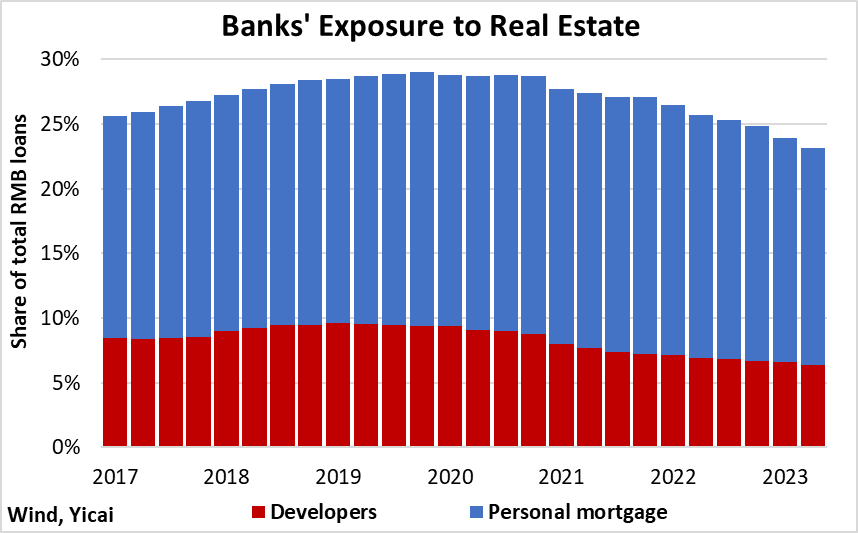

For some time, macroprudential rules have limited the amount that Chinese banks could lend to developers. At the end of June, banks’ loans to developers were close to CNY 15 trillion. This amounted to 6 percent of their local currency loan book, down from 10 percent in early 2019 (Figure 6). The banks also have CNY 39 trillion outstanding in residential mortgages. While this represents 17 percent of their local currency loan book, large down payments, strong household balance sheets and elevated savings rates mean that these exposures are not particularly risky.

Figure 6

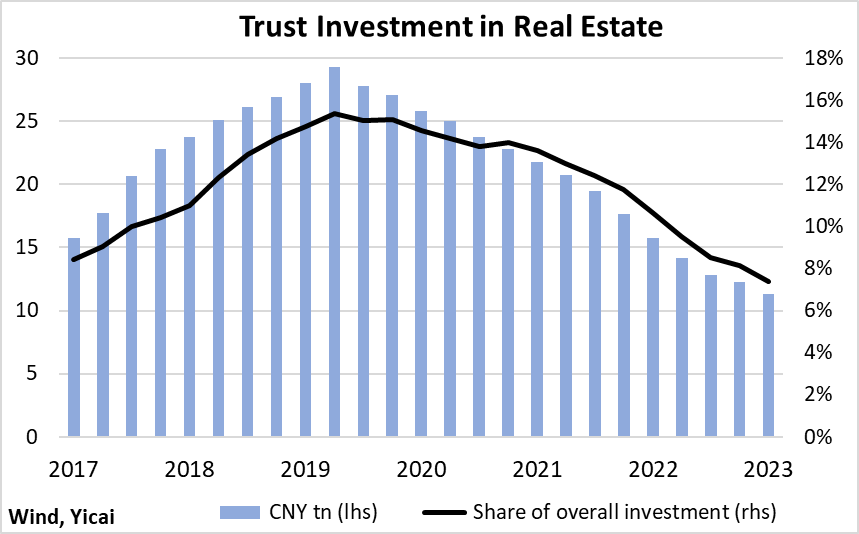

The trust companies have aggressively reduced their investment in developer liabilities from CNY 29 trillion in mid-2019 to 11 trillion as at the end of March (Figure 7). Consequently, their exposure to developers fell from 15 to 7 percent of their overall investments.

Figure 7

A turnaround in floorspace under construction will require a rebound in housing starts. This, in turn, will depend on renewed buyer confidence and a significant pick-up in sales.

The rules for purchasing housing in first-tier cities have recently been liberalized. On August 31, the People's Bank of China and the State Administration of Financial Supervision announced that the down payments needed to buy first and second homes would be unified across the country at 20 percent and 30 percent respectively. Moreover, they pegged the mortgage rates for first-time buyers to the Loan Prime Rate (LPR) minus 20 basis points. Second-time buyers will pay the LPR plus 20 basis points.

Local governments in China had been given considerable scope to implement their own housing market policies. For example, down payments for second homes had been up to 60 percent in Shenzhen, 70 percent in Shanghai and Guangzhou, and as high as 80 percent in Beijing.

Bloomberg reported that the new rules had given rise to a flurry of buying in Beijing and Shanghai and that property developers’ shares jumped. The four first-tier cities only account for 5 percent of China’s population, but 12 percent of the value of new housing sales.

While it is too soon to call a turnaround in the property market, reduced financial stability risks and more accommodative rules, perhaps, limit the downside going forward.