Have China’s CO2 Emissions Peaked?

Have China’s CO2 Emissions Peaked?(Yicai) Dec. 8 -- Scientists have sobering news for the participants in the climate change conference. There is a growing that too much carbon will be emitted in the coming years to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. Nearly 37 billion metric tons of carbon were emitted last year. At this rate, the global carbon budget for keeping warming to 1.5 degrees would be exhausted in just six years.

In this gloomy context, there is encouraging analysis from , a UK-based website covering the latest developments in climate science, climate policy and energy policy. Carbon Brief projects that CO2 emissions from China – the world’s biggest emitter – will peak this year. Carbon Brief’s analysis is comprehensive and I recommend its to you.

During the 75th Session of the United Nations General Assembly in September 2020, President Xi China’s dual carbon goals: emissions will peak before 2030 and carbon neutrality will be achieved by 2060.

Carbon Brief’s projection that China’s emissions have reached their highest point is technically consistent with the announced target. But emissions peaking 7 years before the deadline is a bit of a surprise.

Between 2017 and 2022, the average annual increase in China’s CO2 emissions, from the use of fossil fuels and the manufacture of cement, was just over 230 million tonnes. Moreover, Carbon Brief estimates that they will jump by over 540 million tonnes this year, as the lifting of mobility restrictions in place during the pandemic period has led to a rebound in the demand for petroleum products (Figure 1). However, beginning next year, Carbon Brief forecasts that China’s CO2 emissions will begin to drop.

Figure 1

According to Carbon Brief’s analysis, the peak and subsequent fall in China’s emissions is a result of a “historic expansion of low-carbon energy installations.” Due to China’s rapid electrification – for example, the adoption of new energy vehicles – almost all of the recent increase in its emissions has taken place in the power sector. This means that when power emissions peak, total emissions are likely to follow.

Carbon Brief expects China to add 282 gigawatts of electricity generation capacity from hydro, wind and solar power this year (Figure 2). This would bring clean energy generating to just over 1400 gigawatts and implies a doubling of capacity from 2018.

Figure 2

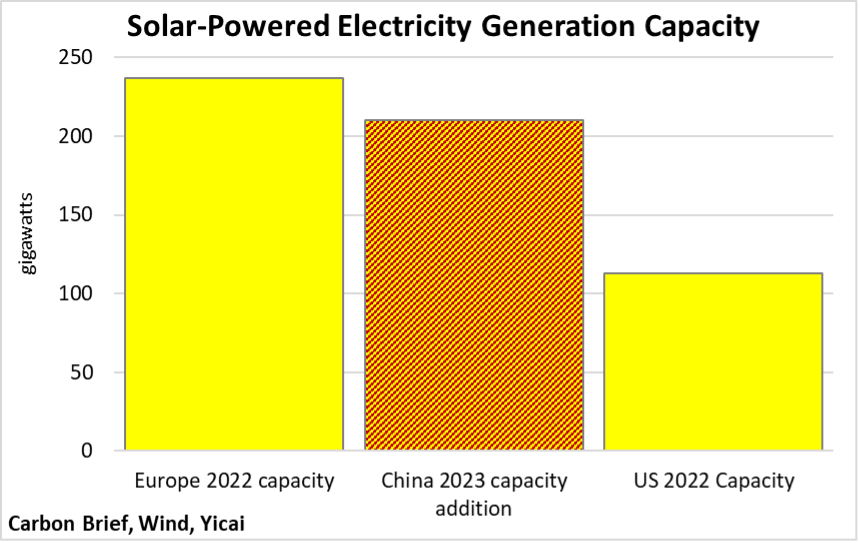

China’s projected 210 gigawatt increase in solar-powered electricity generating capacity this year is particularly impressive (Figure 3). China’s 2023 increment is close to double the US’s entire 2022 capacity and about 90 percent that of Europe’s!

Figure 3

Data from China’s (NEA) show that over the first three quarters of the year, just under half of the new solar capacity added was in the form of large, utility-scale operations (Figure 4). These “clean energy bases” or solar parks are typically located in sparsely populated or desert areas like Inner Mongolia and Gansu provinces.

Most of the solar capacity being installed this year comes from small-scale projects that put panels on the roofs of public buildings and private residences. In July 2021, the NEA that at least half the Party and government buildings be equipped with solar panels. Panels should also be installed on 40 percent of the country’s schools and hospitals, 30 percent of its commercial and industrial facilities and 20 percent of its rural residences.

The NEA that through September, panels have been installed on the roofs of 5 million rural households. These installations are often market-driven as households can by selling the excess electricity their panels produce to the local utility.

According to the NEA, the 5 million households have the capacity to generate 105 gigawatts of electricity. It says that there are 80 million rural households that could potentially host the installations of solar panels. This means that putting panels on the remaining 75 million residences could significantly increase solar capacity.

The marginal costs of wind and solar are comparatively low. Moreover, according to , power from renewable sources such as wind and solar must be sent to consumers first. That means coal-fired power will increasingly be used as a backup for cloudy or windless days.

Still, scaling up China’s rooftop power generation faces challenges. In particular, households have to find ways to the electricity generated by the mid-day sun to be able to sell it at darker times.

Figure 4

In addition to the massive build-up of solar and wind generating capacity, Carbon Brief believes that China’s power generation will benefit from a rebound in hydropower. Hydro will no longer be plagued by the heatwaves and droughts that reduced generation between August 2022 and July 2023. Indications are that water levels in reservoirs have risen to their historical averages and the current El Niño cycle points to above-average rain until February. In addition, the 7 percent increase in hydropower capacity installed between the beginning of 2022 through September 2023 will further boost the contribution of this green power source to China’s energy needs.

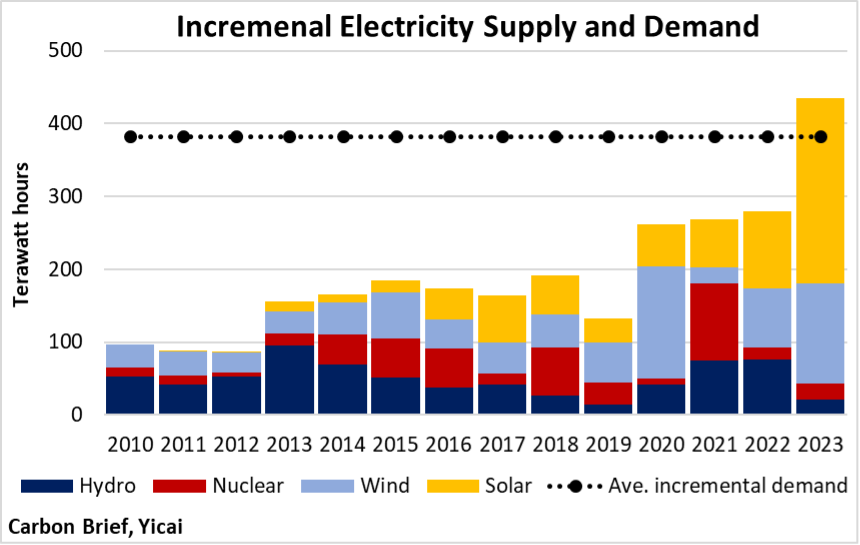

To project the path for China’s CO2 emissions, Carbon Brief calculates the average annual increase in electricity demand (382 terawatt hours) and compares it to the increase in electricity generated from green sources (Figure 5). If the former is smaller than the latter, then the amount of electricity generated from fossil fuels falls and the associated CO2 emissions decline.

Carbon Brief says that given the increase in wind and solar capacity and the rebound in hydropower generation, a decline in China’s CO2 emissions is “essentially locked in” for 2024. Looking further ahead, the demand for fossil fuels will continue to decline if China maintains this year’s pace of green energy capacity additions.

Figure 5

Significantly more non-fossil fuel capacity will likely be added in coming years. China’s foresees non-fossil fuels constituting 25 percent of energy consumption by 2025, up from 17 percent in 2021. But that is only the beginning. According to China’s long-term , non-fossil fuels’ share in energy consumption will rise to 80 percent by 2060. This suggests that massive investments in low-carbon power generation will continue for more than three decades (Figure 6).

Figure 6

It appears that one of the unintended consequences of the downturn in China’s property market is that it freed up the human, physical and financial resources to invest heavily in green energy. With real estate likely to remain in the doldrums for some time, China can make large-scale investments in green power generation without having to worry about creating a labour shortage and stoking inflation.