Has Globalization Peaked?

Has Globalization Peaked?(Yicai Global) July 31 -- In 2010, Bruce Nussbaum published a prescient essay in the Harvard Business Review entitled “Peak Globalization”. He argued that as countries prize sovereignty over multilateralism, national interests over international cooperation and local constituencies over global populations, the costs of globalization will appear to outweigh its benefits.

Almost a decade later, in its analysis of industrial value chains, the McKinsey Global Institute found that globalization had reached a turning point in the mid-2000s. Goods-producing value chains had become less trade intensive and more regionally concentrated, as firms located production close to centers of demand. Emerging market countries’ share of global consumption had risen rapidly, as did their ability to produce world-class products. This meant that their consumers relied less on foreign goods and their producers needed fewer imported intermediate inputs.

Economists have long held that globalization supports higher living standards. For example, Grossman and Helpman discuss four theoretical channels through which international integration promotes growth. First, globalization facilitates the flow of knowledge across national borders. Second, it provides firms with larger markets and economies-of-scale opportunities. Third, it encourages specialization according to comparative advantage. Fourth, it can accelerate the pace of technological diffusion.

Given globalization’s benefits, how worried should we be about the process peaking?

To dig into this question, I rely on the data compiled by KOF, a Swiss research institute. KOF constructs globalization indices which measure its economic, social and political dimensions. KOF’s dataset covers 203 countries over the period 1970 to 2020 and its globalization indices are among the most widely used in academic literature.

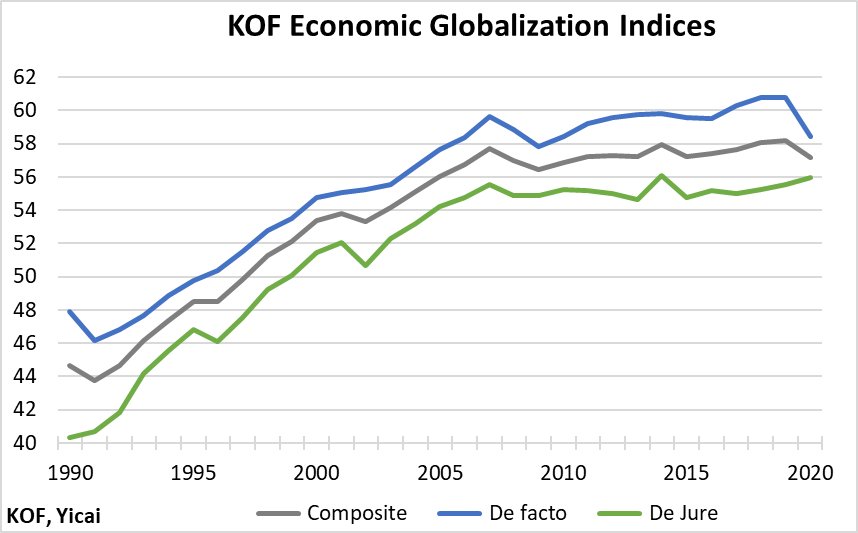

I want to concentrate on KOF’s measures of economic globalization. KOF’s economic globalization index is composed of trade and finance sub-indices, with each having a 50 percent weight (Figure 1). According to KOF, the process of globalization has stagnated since the Global Financial Crisis. Subsequently, the trade conflict between the US and China has weighed on trade openness. Finally, the outbreak of the pandemic reduced trade in services, in particular tourism and transport.

Figure 1

One of the unique aspects of KOF’s work is that it measures globalization on both de facto and de jure bases. While de facto globalization measures actual international flows and activities, de jure globalization measures policies and conditions that, in principle, foster these flows and activities. The literature suggests that de facto and de jure globalization can have quite different effects on economic outcomes.

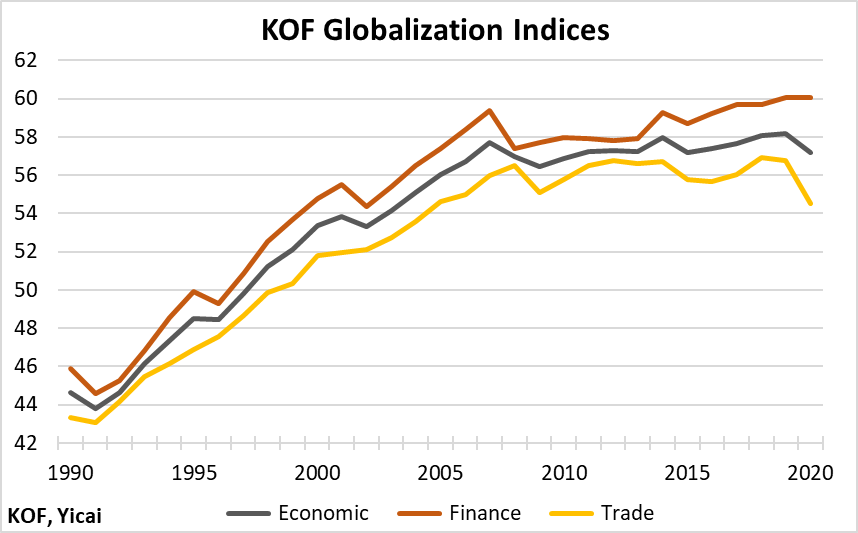

Half of KOF’s trade globalization index is composed of de facto elements. Trade in services is the largest de facto variable, followed by trade in goods and a measure of trading partner diversity (Figure 2).

The other half of KOF’s trade globalization index is made up of de jure elements, policies that facilitate and promote trade flows between countries. The trade taxes variable measures income taxes on trade. The trade regulation variable is composed of the prevalence of non-tariff barriers and the compliance cost of exporting. The tariffs variable is the unweighted mean of tariff rates. The trade agreements variable measures the stock of free trade agreements.

Figure 2

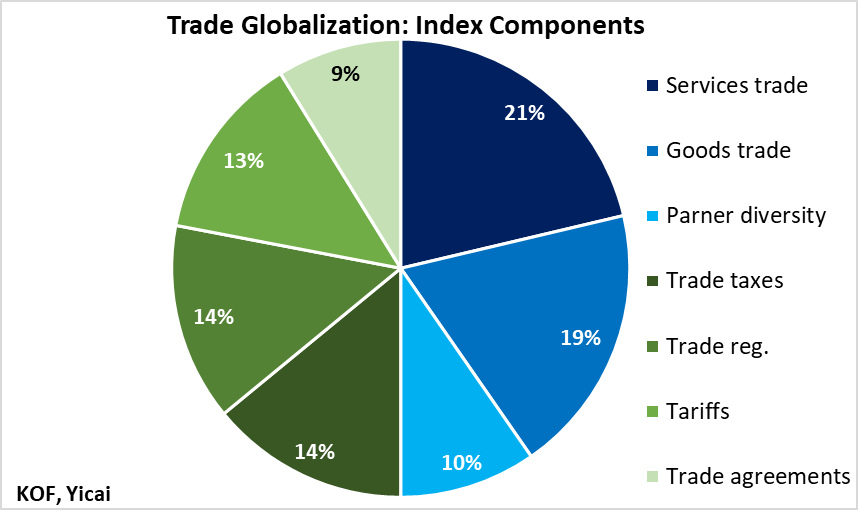

The trends in KOF’s trade globalization de facto and de jure sub-indices have diverged in the last five years (Figure 3). By 2020, de facto trade globalization had dropped to a 25-year low. In contrast, de jure trade globalization continued to increase. While its rate of increase has slowed since the Global Financial Crisis, it appears to have picked up somewhat since 2015.

Figure 3

It is possible that the KOF’s data, which end in 2020, paint too negative a picture of de facto trade globalization.

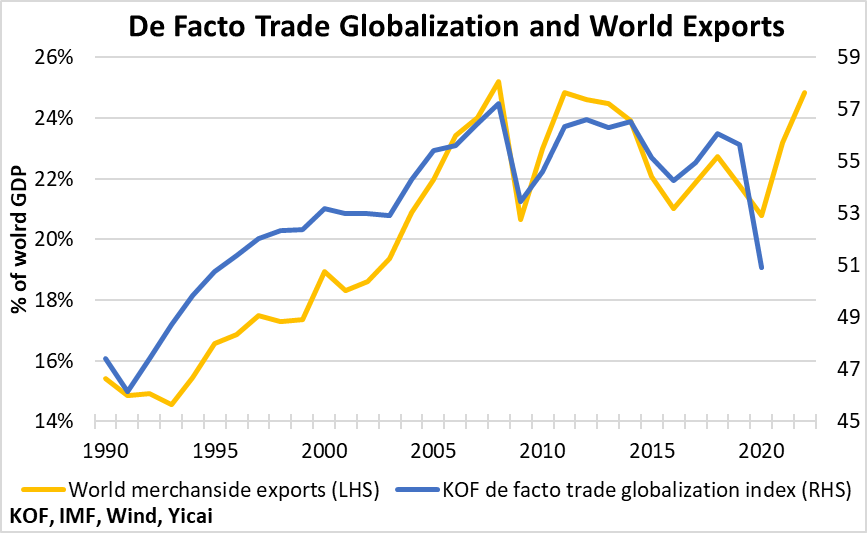

In 2021 and 2022, world merchandise exports rebounded sharply from their 2020 low. By 2022, world merchandise exports were the equivalent of 25 percent of global GDP, just a hair below their 2008 peak (Figure 4). While merchandise trade only represents a portion of the information that KOF considers, it is likely that the data for 2021 and 2022 will show renewed strength in de facto trade globalization.

Figure 4

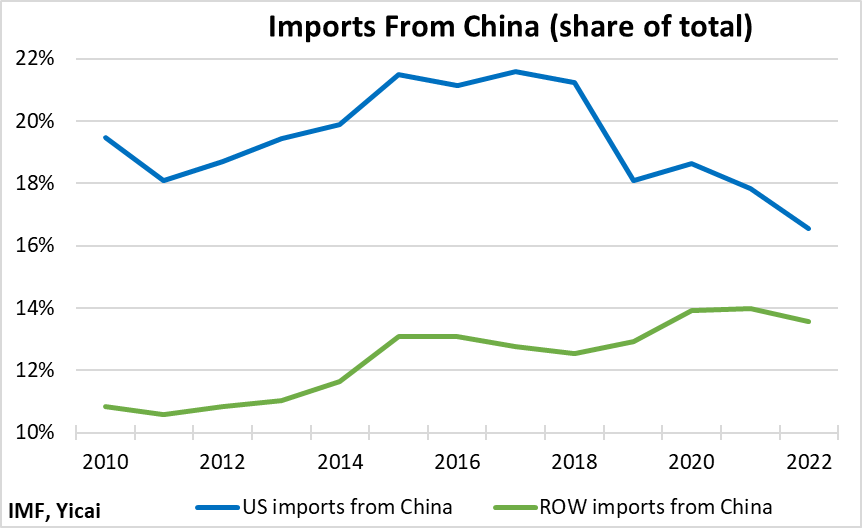

According to analysis by DHL and NYU’s Stern business school, the trade tensions between the US and China have not led to a generalized fragmentation of international activity. Thus, it may not be having much of an impact on de facto trade globalization.

The share of the US’s imports coming from China peaked at 21.6 percent in 2017, before the Trump Administration imposed its tariffs. By 2022, China’s share of US imports dropped to 16.5 percent (Figure 5). While China’s imports lost market share in the US, their share increased in the rest of the world. This points to the unique factors affecting China-US trade. It suggests that China’s de facto trade globalization has not yet peaked.

Figure 5

Indeed, even within the US, China’s loss of import share was not generalized – it depended significantly on the application of tariffs.

Analysis by the Peterson Institute shows that, for product categories subjected to the highest tariffs, US imports from China were 22 percent lower in mid-2022 than they were before the start of the trade war in 2018. Imports of these products from the rest of the world were up 34 percent. In contrast, for those products that did not experience a tariff increase, the US’s imports from China were up 50 percent, while those from the rest of the world were only up 38 percent.

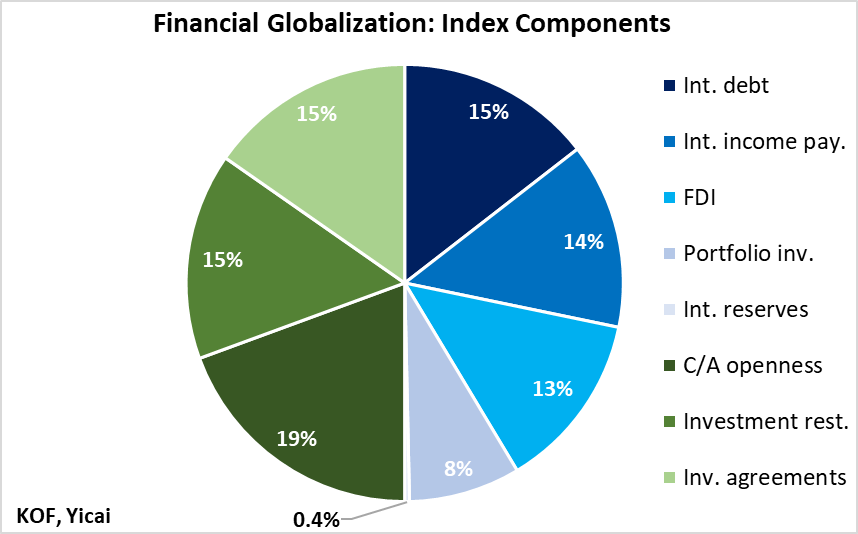

KOF’s financial globalization index is also composed equally of de facto and de jure elements (Figure 6). Most of the de facto variables represent the sum of the stocks of international assets and liabilities normalized by GDP. The international income payments variable is the sum of cross-border payments and receipts as a share of GDP.

De jure financial globalization is designed to measure the institutional openness of a country to international financial flows and investments. The largest variable is capital account openness, which is proxied by the Chinn-Ito index. The investment restrictions variable is taken from the WEF Global Competitiveness Report. Finally, the investment agreements variable is the number of international investment agreements and treaties with investment provisions.

Figure 6

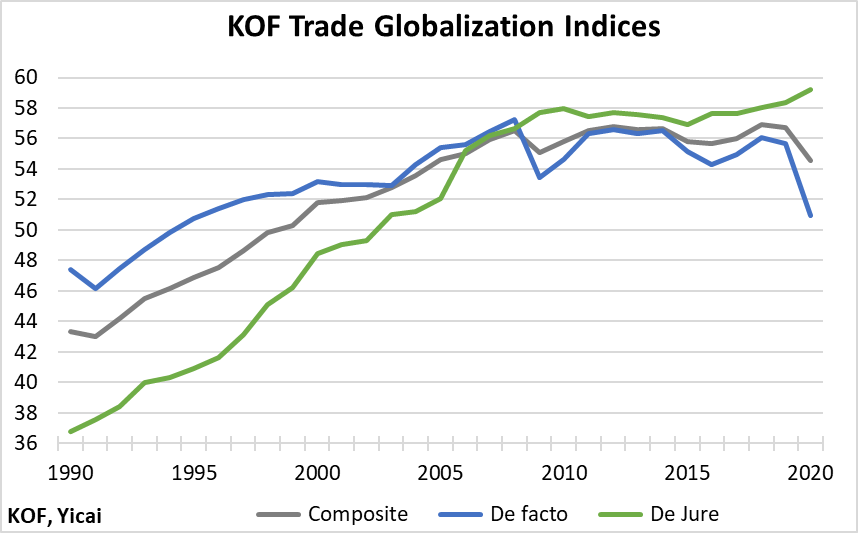

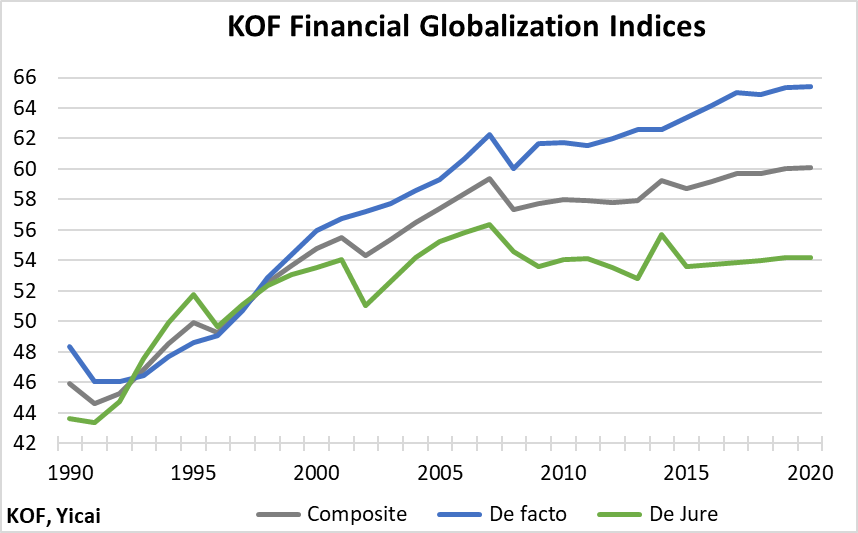

The trends in financial globalization are almost a mirror image of those of trade globalization. De facto financial globalization has continued to increase despite de jure financial globalization not having made much progress in the last two decades (Figure 7).

Figure 7

KOF provides convincing econometric evidence that economic globalization supports per capita GDP growth.

Its analysis shows that the positive impact on growth from trade and financial globalization comes from institutional liberalization rather than greater economic flows. It is the de jure trade and financial globalization indices that are associated with more rapid per capita GDP growth. There is no significant relationship between growth and the de facto indices.

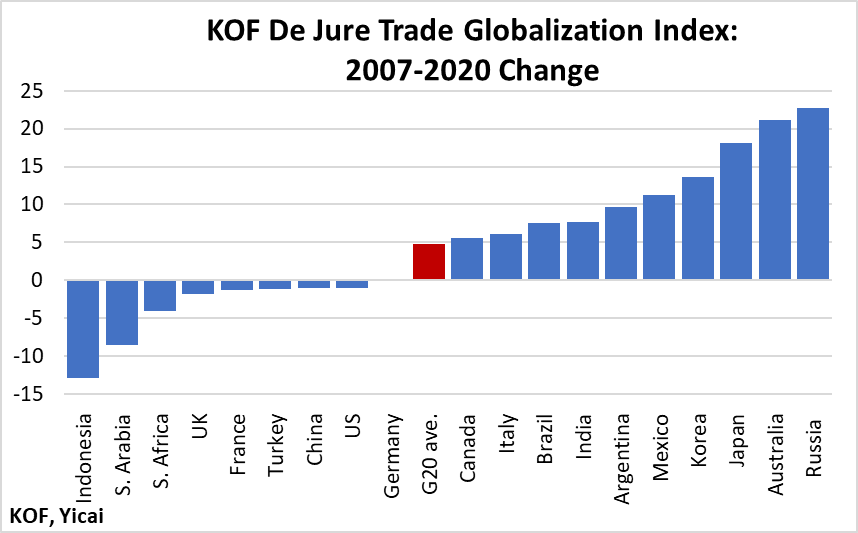

This is good news for policymakers because it puts the keys to higher growth in their hands. Looking across the G20 countries, the de jure trade globalization index rose by just under 5 points between 2007 and 2020. However, several countries took significant steps to liberalize their trading regimes (Figure 8).

Figure 8

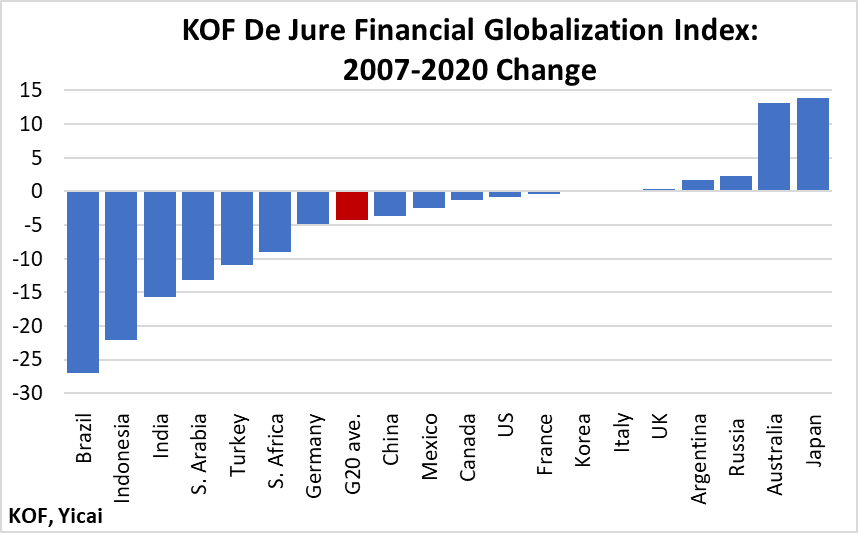

The G20 countries were more cautious when it came to financial liberalization. On average, the de jure financial globalization index fell by close to 5 points over the same period. Most countries tightened financial controls, likely because of fears of financial contagion stemming from shocks like the Global Financial Crisis (Figure 9).

Figure 9

While globalization is proceeding at a much slower pace than during the years prior to the Global Financial Crisis, I think it is premature to say that it has peaked.

KOF’s measure of de facto globalization shows a precipitous drop in 2020 but this appears to be due to the pandemic’s effect on trade flows rather than a generalized decoupling (Figure 10). De facto financial globalization continued to increase and more recent data on merchandise exports suggests that we should see a rebound in de facto trade flows.

KOF’s de jure globalization index actually reached a new high in 2020, as measures were taken to liberalize trade flows (Figure 10). Nevertheless, the de jure economic globalization index has only increased marginally since 2007.

Given the importance of institutional liberalization in supporting growth, policymakers need to find ways to further de jure globalization. Multilateral or regional fora, in which liberalization proceeds in a coordinated manner among interested parties, may be the best option here.

Figure 10