GDP Ends 2021 on a High Note

GDP Ends 2021 on a High Note(Yicai Global) Jan. 21 -- On January 17, China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) released its for 2021. Real GDP grew by 4.0 percent in the fourth quarter, exceeding of 3.6 percent growth.

Although the NBS reported a myriad of data points, I would like to zero in on one that was confined to Footnote 2: the quarter-over-quarter growth of GDP in Q4. As the points out, “The quarter-on-quarter figure is a far more accurate measure of the economy’s health than year-on-year headline figures, which have whipsawed down and then back up because of the Covid-19 pandemic.”

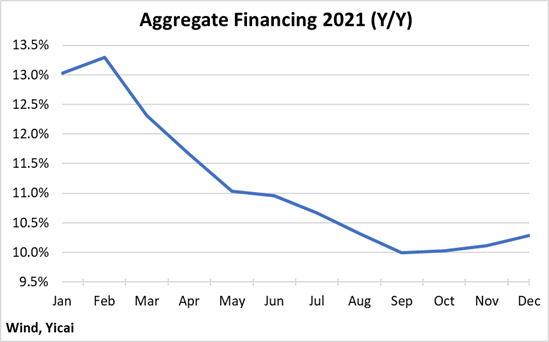

In the fourth quarter, real GDP grew by 1.6 percent. This was a good number. It was, by far, the fastest quarterly growth rate of the year and it even exceeded 2019’s average of 1.4 percent (Figure 1).

Figure 1

When the US releases its National Accounts, all of the focus is on the quarter-over-quarter rather than year-over-year growth. Moreover, the US reports its quarterly growth at annual rates to make it comparable with the full-year’s number. At annual rates, China’s 1.6 percent becomes 6.6 percent. This is faster than full-year growth in 2019 (6.0 percent), the average of 2020 and 2021 (5.2 percent) and expectations for 2022 (5.0 percent).

What should we make of the rapid growth in Q4? Does it suggest that the economy might be stronger than expected in 2022?

Forecasters are fond of saying that “one data point does not make a trend”. Indeed, rather than portending a good start to 2022, the strength in Q4 could just as easily be “catch up” after the weakness in Q3, when output was constrained by supply shocks.

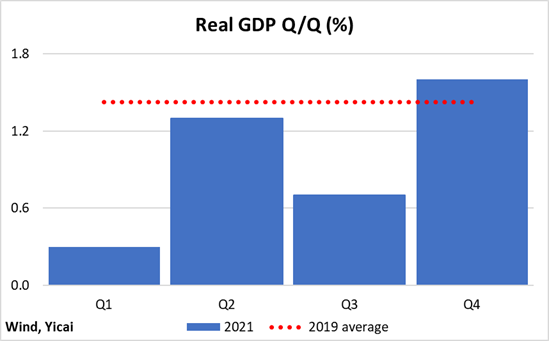

The economy’s true near-term trend likely lies somewhere between growth of 6 percent during 2018-19 (the slope of the dotted red line in Figure 2) and the 4 percent growth over the last four quarters (the slope of the blue line from 2020Q4, where it diverges from the 2018-19 trend).

Figure 2

The Leadership has described the economy as being pressured by shrinking demand, supply shocks and weakening expectations. The economy’s trend growth will depend on how long these three pressures last. Let’s see what light some of the NBS’s other key data can shed on this question.

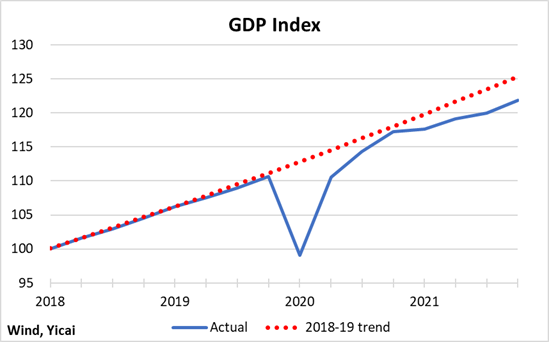

Figure 3 presents the contributions of consumption, investment and net exports to GDP growth over the past three years. We want to average the outcomes in 2020 and 2021 to smooth out the volatility caused by the pandemic. Then we want to compare this two-year average to 2019. This will allow us to assess the state of the recovery.

As we noted above, average growth in 2020-21 was about three-quarters of a percent lower than it had been in 2019. This weakness came entirely from consumption. It was partially offset by stronger net exports. Investment’s contribution was essentially unchanged.

Figure 3

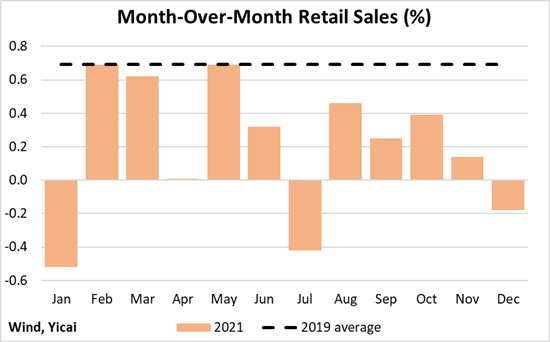

The weak demand the Leadership speaks of is most evident in consumption. The ongoing battle against Covid and the downturn in the real estate market are pressuring consumer spending. Indeed, retail sales slumped further in December after sustained weakness all year long (Figure 4).

Figure 4

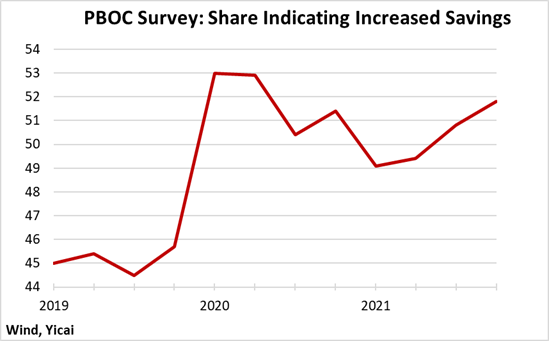

The PBOC conducts quarterly surveys of consumer sentiment. It askes consumers about their spending and savings plans. The share of respondents that indicated they planned to increase savings spiked following the outbreak of the pandemic in early 2020 (Figure 5). While it has edged down slightly, the share of respondents that indicated they would save more remains well above its 2019 level. When the Leadership speaks of weakening expectations, they likely have this increase in consumers’ precautionary saving in mind.

Figure 5

Even though the strong measures China takes to keep Covid from spreading have an impact on local supply chains, the situation is even worse overseas. The relative resilience of China’s production is a key factor behind the 30 percent jump in its exports (in dollar terms) in 2021. China sells its exports to a wide variety of countries. The growth of China’s sales in these markets was strong across the board.

China’s trading partners’ inventories remain low. History suggests that low levels of inventories are associated with strong restocking demand. This tends to boost imports from China (Figure 6). Given their much larger base, it is unlikely that Chinese exports will increase by 30 percent again in 2022. However, restocking demand should support robust exports, at least for the first half of the year.

Figure 6

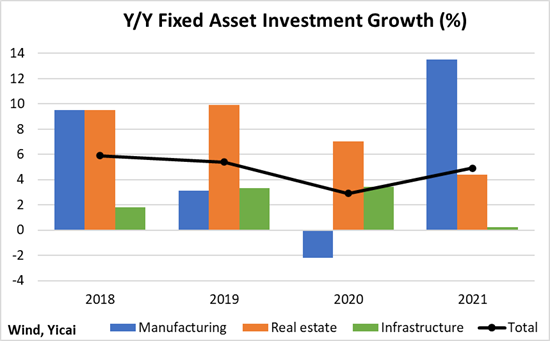

Investment growth rebounded sharply in 2021. Moreover, its composition shifted toward manufacturing and away from real estate and infrastructure (Figure 7). Manufacturing firms were increasingly profitable in 2021. This gave them the incentive to reinvest in their businesses. Increased investment in manufacturing in 2022 should help improve China’s productivity.

Figure 7

In Q3, China suffered from a coal shortage that led to power rationing and a lack of chips that restrained auto manufacture. These bottlenecks have largely been resolved. Domestic coal mines sharply increased their output in the fourth quarter. Similarly, passenger car production rose steadily to year-end.

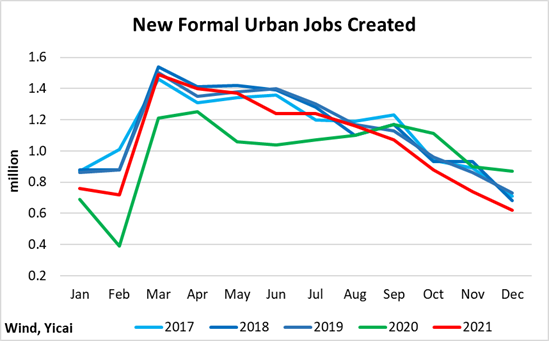

The Leadership’s target for the creation of 11 million new jobs in the formal urban labour market was exceeded by a comfortable margin. Moreover, the unemployment rate has returned to pre-pandemic levels. Still, there are signs that the economy is being pressured by labour supply issues. Since August, the number of new jobs created has fallen below the levels recorded in previous years (Figure 8).

Figure 8

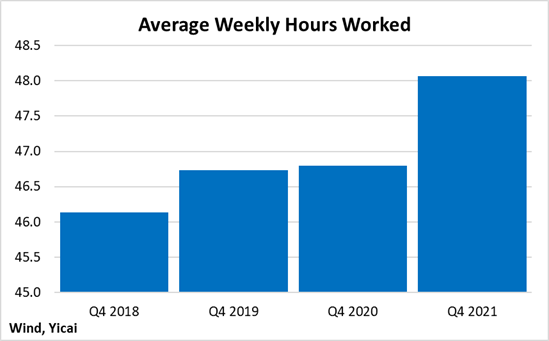

Despite the slowing employment growth, the demand for labour appears to be strong, as average hours worked in the fourth quarter were well above previous years’ levels (Figure 9).

Figure 9

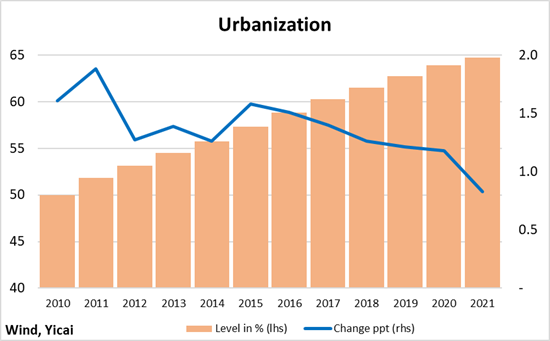

Sluggish labour supply growth, in part, appears to be related to a slower rate of urbanization (Figure 10). While people are still moving from the countryside to the city, they are doing so at a slower rate. By broadening the social safety net and providing a more predictable environment for renters, policy could remove some of the disincentives to migration.

Figure 10

The near-term growth trend will depend on the evolution of the pandemic. Despite a new wave of infections in January, surveys conducted by the Ministry of Transport suggest that twice as many people could return home for Chinese New Year as did in 2021. GDP growth in the first quarter depends heavily on spending related to New Year’s festivities, so an increased willingness to travel would be quite positive for growth.

It is most likely that growth will accelerate significantly from the 4 percent recorded in the last four quarters. Even if all of the strength in Q4’s quarterly growth was “payback” from a weak Q3, average quarterly growth over Q3-Q4 would still be 4.7 percent at annual rates.

Moreover, an increasingly supportive policy environment could provide the economy the momentum it needs to exceed 5 percent growth in 2022.

Fiscal policy appears to have been a drag on growth in 2021. However, NBS Commissioner Ning Jizhe that government-sponsored infrastructure spending will accelerate as key projects identified in the 14th Five-Year Plan are launched.

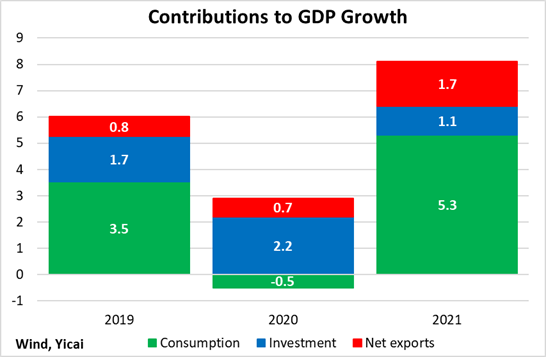

Similarly, monetary policy tightened through most of 2021 but became more accommodative in Q4 (Figure 11). With cuts to the and the in December and a reduction in the rate on after the release of the National Accounts, the PBOC is seeking to ensure that the recovery in credit demand continues.

Figure 11