EU-China Trade: A Textbook Analysis

EU-China Trade: A Textbook Analysis(Yicai) Dec. 19 -- Josep Borrell is the EU’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and the Vice-President of the European Commission. He offered a of the recent EU-China Summit, the first in-person meeting between the senior leaders of the world’s second and third biggest economies since 2019. According to Borrell, the quality of the dialogue improved, with both sides recognizing the importance of their relationship and the need to manage their differences.

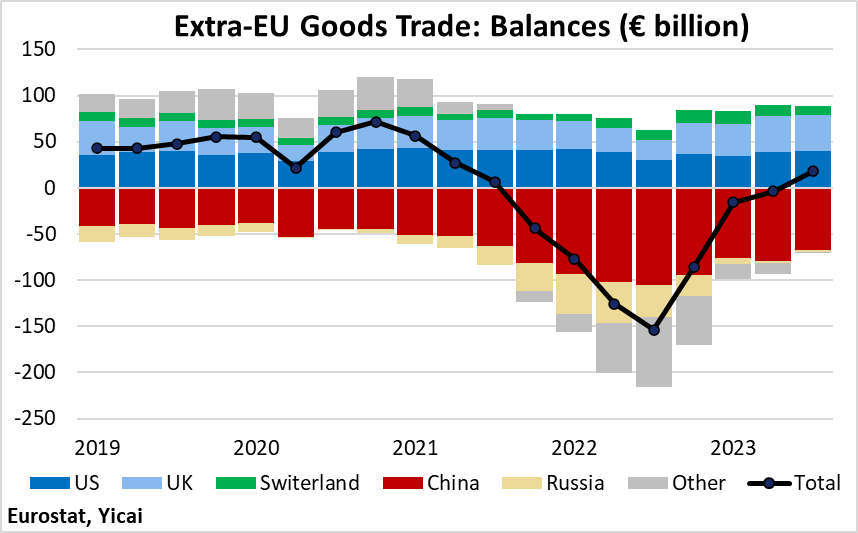

I was surprised that the first policy area Borrell highlighted in his report was the bilateral trade balance. He noted that the EU’s trade deficit with China more than doubled between 2020 and 2022, reaching close to 400 billion euros. In Borrell’s view, the China-EU trading relationship has become “critically unbalanced”.

I believe Borrell’s focus on the bilateral trade balance is misplaced.

Greg Mankiw is a Professor of Economics at Harvard University and author of the classic textbook “” now in its 11th printing. Mankiw that, from a macroeconomic perspective, what counts is a country’s overall trade position rather than bilateral balances. This is because it is the country’s overall balance with all of its trading partners that tells us if a country’s savings and investment may be misaligned.

Mankiw uses his own experience to illustrate the difference between bilateral and overall balances in a 2018 New York Times . It appears that the Trump Administration was also confused on this point.

When Mankiw goes out to dinner, he gets a meal and the the restaurateur receives money. Thus, he runs a deficit with the restaurant. Now, Mankiw would be delighted if the restaurateur bought one of his books to balance the trade but he would be crazy to boycott restaurants that didn’t want to add to their collection of economic texts.

Mankiw can run permanent deficits with restaurants because he is in surplus with the New York Times. He receives more from the newspaper for his columns than he pays for his subscription. That’s a bilateral trade surplus for him and a bilateral trade deficit for The Times. Nonetheless, they both gain from the relationship.

Mankiw says that if he were to persistently live beyond his means – if the sum of his bilateral deficits exceeded those of his surpluses – that could be problematic. But the problem would be his financial planning, not disreputable trade partners.

According to Mankiw, bilateral trade balances receive more attention than they deserve because international relations are conducted country-to-country and politicians are naturally drawn to bilateral trade statistics. However, most economists believe that bilateral trade balances are not very meaningful.

With Mankiw’s folksy example in mind, let’s look at the data that provides on the EU’s goods trade.

Between 2019Q1 and 2021Q2, the EU ran an overall trade surplus. Its bilateral deficits with China and Russia were more than offset by surpluses with the US, the UK, Switzerland and Other countries (Figure 1).

From 2021Q2 to 2022Q2, the EU’s imports increased much more rapidly than its exports. According to Eurostat much of the rise in imports came from an increase in the price of .

The EU’s deficit with China increased over this period as well. This is because, in the aftermath of the pandemic, the EU’s demand recovered more rapidly than its supply, and imports were needed to fill the gap. The EU’s deficit with China rose by 51 billion euros. Over the same period, its balance with Other countries shifted from surplus to deficit, a swing of 89 billion euros.

The EU’s overall trade deficit began to narrow in 2022Q3. By 2023Q3, it was again running an overall trade surplus. Reflecting these cyclic developments, the EU’s deficit with China in the first three quarters of this year was 77 billion euros smaller than the same period a year ago.

Figure 1

The EU’s trade imbalance with China is not particularly large. In the last four quarters, it is the equivalent of 2 percent of EU GDP. Indeed, the EU runs much bigger imbalances with Switzerland and the UK. Its surpluses with these countries account for 6 and 4 percent of their GDPs, respectively.

Borrell blamed some of the trade imbalance on “limited market access for foreign companies in China”. However, his views seem to be at odds with those of European companies here on the ground.

This summer, the European Chamber of Commerce in China released the latest edition of its . The Chamber found that the public health measures China undertook in the wake of the pandemic did make operations here much more difficult. But foreign firms were not singled out. Indeed, European companies report that they are being treated better and better over time. In the Chamber’s most recent survey, 69 percent of the firms said that they were treated at least as well, or even better, than domestic ones. This is up from just 45 percent in 2015 (Figure 2).

Figure 2

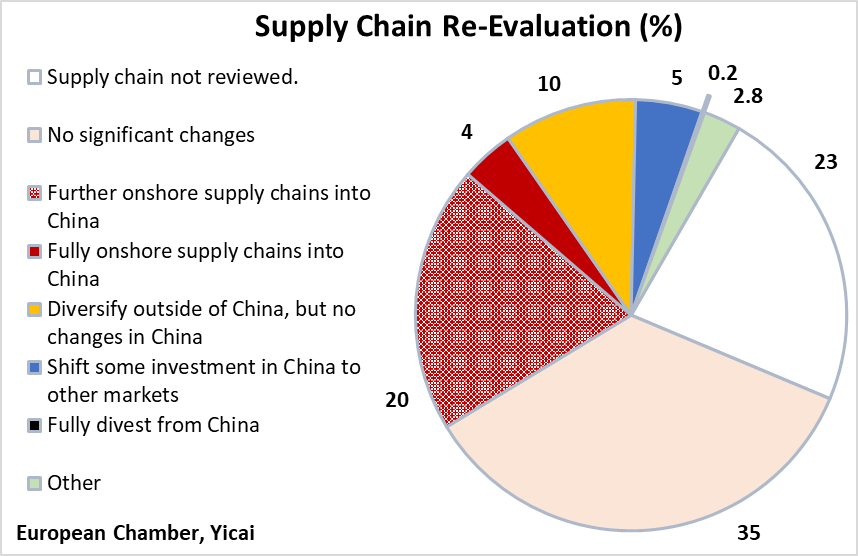

Given this systematic improvement in the business environment, it is not surprising that supply-chain de-risking is unlikely to result in a significant exodus of European firms.

The Chamber asked its member companies how their supply chains are likely to evolve. Only 0.2 percent of the respondents said that they would fully divest from China (Figure 3). An additional 5 percent said that they would shift some investments from China to other markets. On the other hand, 20 percent of the respondents said that they would further onshore their supply chains into China with an additional 4 percent saying they would fully onshore their supply chains. So, for European firms at least, it appears that supply-chain de-risking could be a net positive for China.

Figure 3

Borrell ends his report on a positive note. He says that China remains a pivotal partner for the EU in addressing many global challenges, including climate, biodiversity, debt, health, and international stability. And he promises that the EU will continue to engage at all levels. That’s good news because where there is a will to engage constructively, there is a way to manage differences.