China’s Two Sessions: Three Macroeconomic Takeaways

China’s Two Sessions: Three Macroeconomic Takeaways(Yicai Global) March 12 -- With the convening of the Two Sessions in Beijing, this has been a great week for China policy wonks like me.

The Two Sessions are the annual meetings of the National People’s Congress (China’s parliament) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (China's top political advisory body).

There has been so much information released this week, it is easy to get lost in the details. So, I want to step back and focus on three key macroeconomic takeaways.

In his Report on the Work of the Government, Premier Li Keqiang said, “As a general target, China’s growth rate has been set at over 6 percent for this year.”

It is easy to misunderstand this target. Indeed, most economists believe that GDP growth will be well above 6 percent this year. For example, according to the Yicai Research Institute’s Chief Economists Survey, growth is expected to reach 8.8 percent this year. I’m even more bullish. I think 10 percent growth is likely. But Premier Li is not simply setting an easy-to-meet low bar. He is telling us that 6 percent is the minimum rate of growth policymakers will tolerate – macroeconomic policy is likely to loosen if growth falls below 6.

Six percent growth sounds pretty rapid. And the Chinese government would normally be pretty happy if the economy grew this fast. But not this year. That’s because growth for 2020, as a whole, was really weak, but the rebound was extremely strong in the second half.

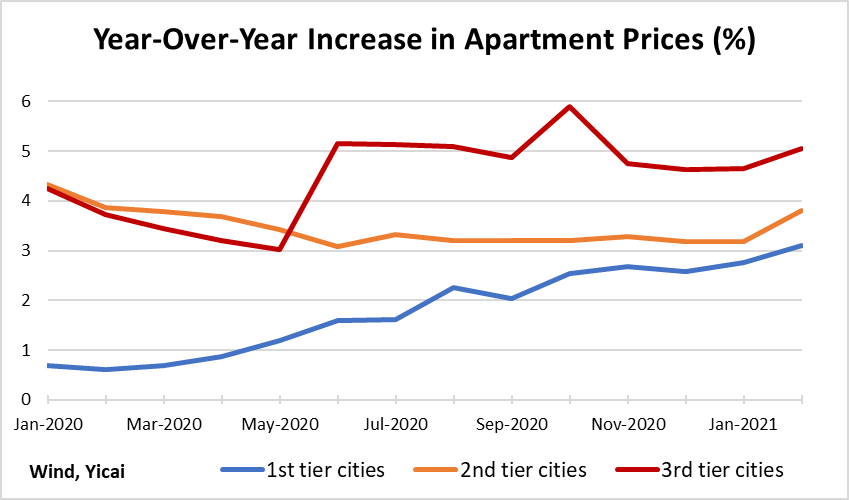

Figure 1 shows that in the fourth quarter of last year, the level of GDP was about 6 percent higher than the 2020 annual average. That means that China can achieve 6 percent growth in 2021 even if the economy simply maintained economic activity at its end-2020 level.

Figure 1

While the headline number would look good, 6 percent growth would mean the economy had essentially stagnated. The growth the economy gets from standing still is called the “base effect”. Growth this year is inflated by a low base last year.

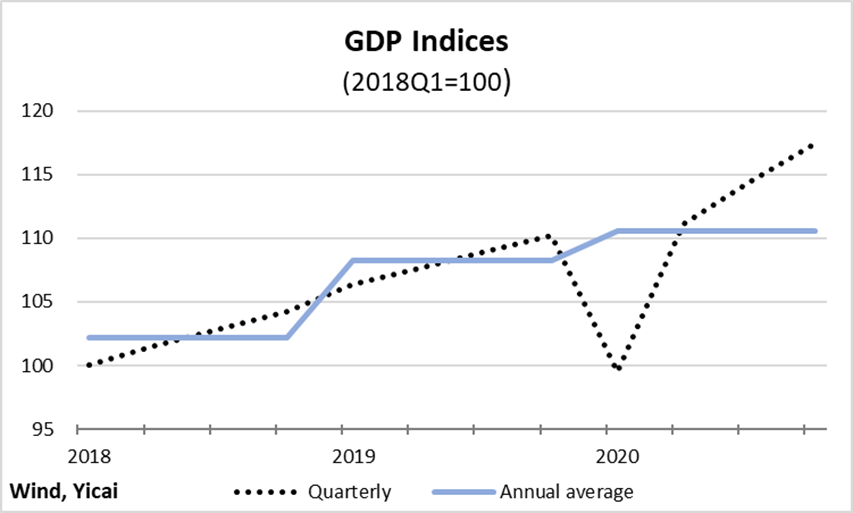

In his Work Report, Premier Li also set a target for urban employment: 11 million new jobs. As Figure 2 shows, actual new urban employment growth typically exceeds the target by more than 2 million jobs. But here too, the target is best thought of as a floor, rather than an objective.

The added benefit of the urban employment target is that new jobs created can be tracked on a monthly basis – so we can have a sense of whether or not the government is worried. The new urban jobs data were particularly useful last year for monitoring the pace of the recovery.

Figure 2

So, our first takeaway is that the government has set transparent indicators on the minimum acceptable economic performance for 2021.

From my perspective, it might also be useful if it set ceilings as well as floors. Afterall, China is essentially at full employment and it faces both upside and downside risks. It would be good to know when the authorities considered growth too fast and at what point policy would have to focus on cooling an over-heated economy.

Given economy-watchers’ fixation with “meeting the target”, perhaps the government could consider announcing a broad range for acceptable rates of growth – a ceiling and a floor – to anchor expectations.

In 2020, fiscal policy was quite stimulative, though not as stimulative as the budget intended.

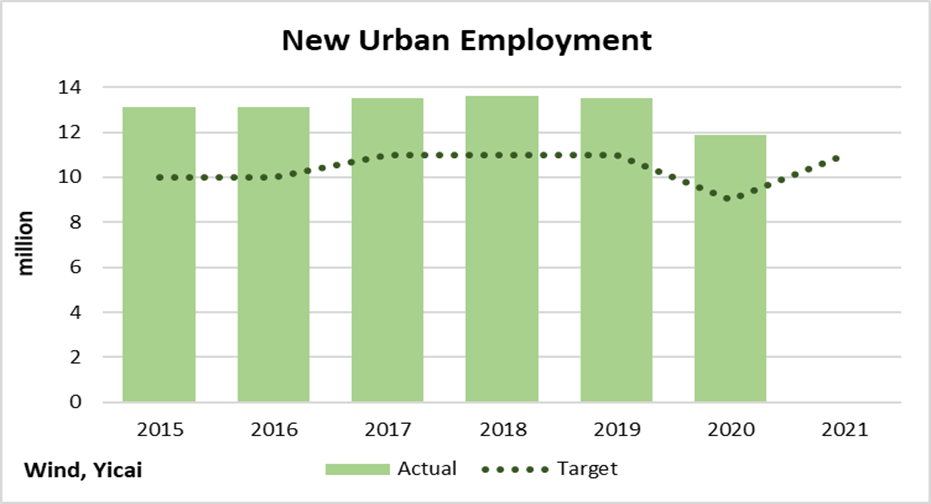

As Figure 3 shows, the headline (accrual) deficit only captures a portion of the government’s fiscal support.

To assess the fiscal stance, I sum the headline national deficit, any withdrawals from or payments into the fiscal reserve fund, extra-budgetary bond issuance and the contribution from government-managed funds. Luckily, all these “below the line” items are available in the budget document, which was also released during the Two Sessions.

Between 2019 and 2020, the adjusted national deficit increased from 7.3 to 8.7 percent of GDP. The difference in the deficits – 1.4 percent of GDP – gives a broad measure of fiscal support. Based on last year’s budget document, I had expected support to be around 3.7 percent of GDP. As it turned out, local governments unexpectedly ran surpluses on their real-estate related funds.

In 2021, the adjusted national deficit is budgeted to fall to 8.1 percent of GDP, implying that fiscal policy will be a drag on growth of 0.6 percent. Given expectations of growth in the 8.8 percent range, the budgeted fiscal tightening is small. And that is our second takeaway.

Figure 3

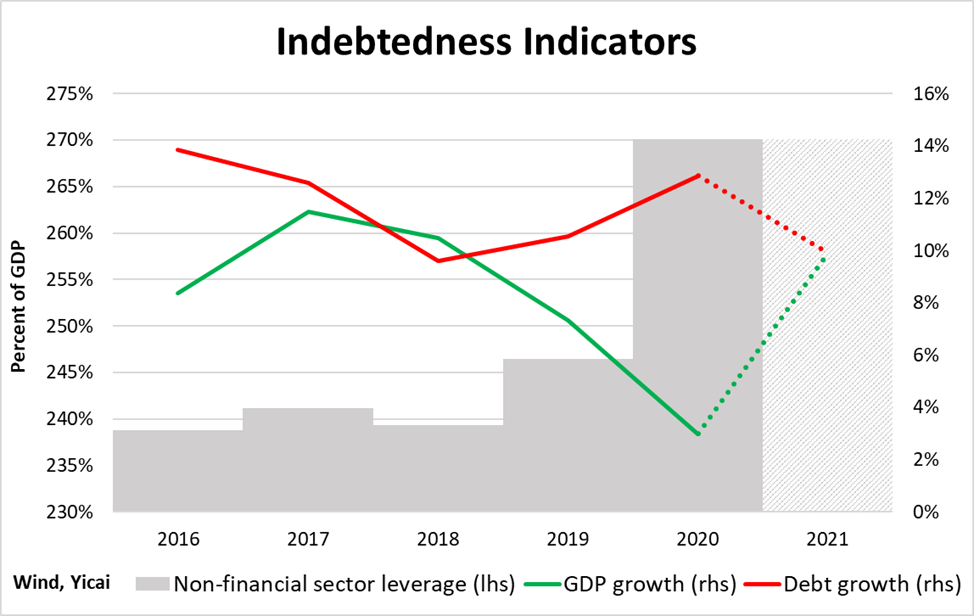

Turning to monetary policy, Premier Li says that the money supply and aggregate financing will grow “in step” with nominal GDP and that the macro-leverage ratio will remain “stable”.

In normal times, a neutral monetary policy would have the money supply growing at essentially the same rate as nominal GDP. A neutral credit policy would keep the debt-to-GDP ratio basically stable. But these are not normal times.

Figure 4 shows the growth of nominal GDP and non-financial sector debt and the macro-leverage ratio (non-financial debt divided by GDP). Last year, nominal GDP increased by 3 percent while debt rose by 13 percent. As a result, the macro-leverage ratio jumped from 247 to 270 percent of GDP.

We project nominal GDP growth of 10 percent in 2021, based on the budget’s planning assumption (the budgeted deficit of CNY 3.57 trillion is expected to amount to 3.2 percent of GDP). We assume the same rate of growth for debt, such that the macro-leverage ratio remains unchanged at 270 percent.

If the monetary authorities are, indeed, targeting 10 percent nominal GDP growth, they risk ignoring the “base effect” and over-estimating how rapidly the economy is growing. If they were to target underlying growth, which is likely a few percentage points lower, they could edge the macro-leverage ratio closer to its pre-pandemic level and reduce the credit overhang.

Figure 4

China’s monetary authorities are in a tough place.

On the one hand, core consumer price inflation is close to zero. This argues for easy monetary conditions, as Premier Li announced a 3 percent consumer price inflation target for 2021.

On the other hand, a growing commodity price cycle is feeding into higher producer price inflation. While producer prices only rose by 1.7 percent, year-over-year, in February, that was their fastest rate since November 2018. Rising producer prices augur poorly for future consumer price inflation.

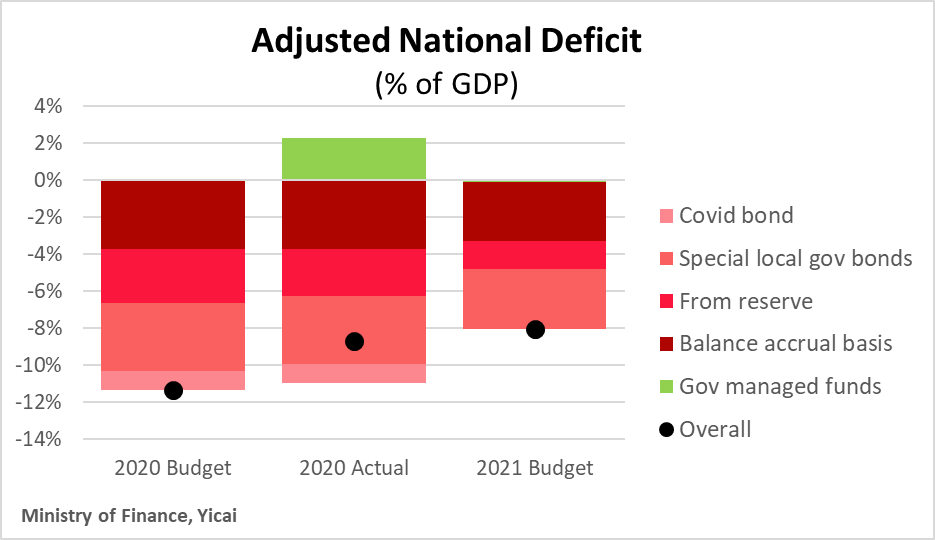

Perhaps more importantly, new home prices are accelerating, with the fastest rate of increase in Third Tier Cities (Figure 5). This has led a number of municipalities including Shanghai, Wuxi, Hangzhou, Shenzhen and Beijing to tighten rules on the purchase of real estate.

And this is our third takeaway: monetary policy will remain accommodative in 2021 and the authorities will increasingly rely on macroprudential measures to check a budding real estate boom.

Figure 5