China’s Path to High-Income Status: Lessons from Recent Success Stories

China’s Path to High-Income Status: Lessons from Recent Success Stories(Yicai Global) Nov. 16 -- Last week, we looked at scenarios for how fast China needs to grow to become a “moderately developed country” in the next 15 years. This week, we examine the experiences of a set of countries that was successful in achieving high-income status over the last 15 years. In order to distill lessons for China, we compare these countries against a second set, which remained stuck in the “middle-income trap”.

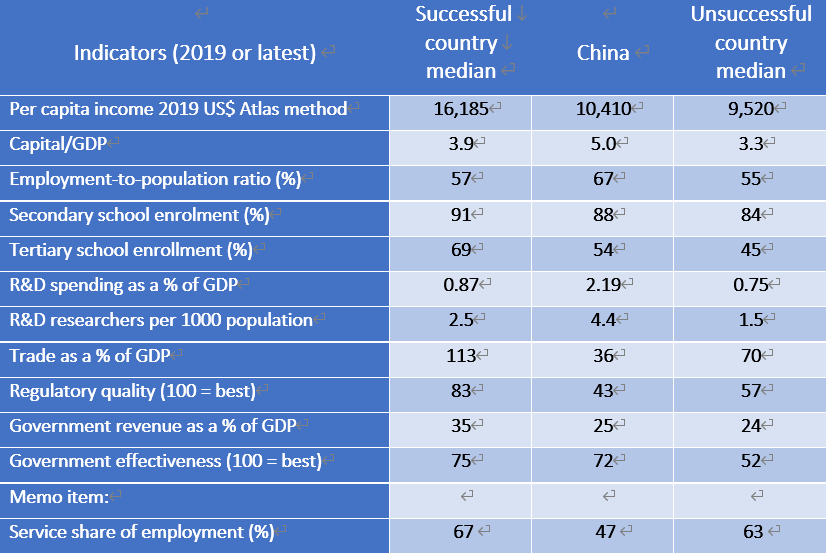

We begin in 2000 with 16 countries which had similar levels of per capita income. Nineteen years later, 10 of these countries successfully crossed the World Bank’s high-income classification threshold, which is indicated by the dotted line in Figure 1. Drawing on economic theory, we want to find out why some countries were successful while others were not.

Figure 1

We will be looking at a series of correlations. We need to be aware that correlation does not imply causation and that causation can run in both directions. For example, we will find that high-income status is correlated with educational attainment. It is quite likely that an educated work force is needed to attain high-income status. But it can also be the case that rich countries have more money to spend on schooling and this is what the correlation is picking up.

To address this problem, we assess the two sets of countries by taking snapshots of their fundamentals in 2009. The premise here is that the fundamentals in 2009 are more likely to be causal of outcomes in 2019 than vice versa.

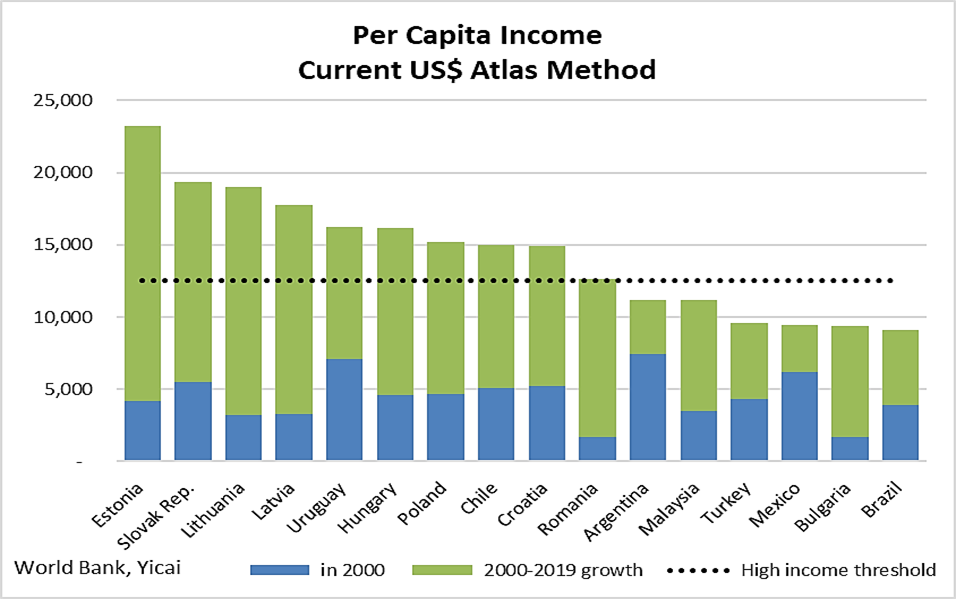

Economists have long relied on insights from the Solow model to explain differences in wealth between countries. In this model, high per capita incomes result from the extensive use of physical inputs – capital and labour – and elevated productivity – the efficiency with which these inputs are used.

Figure 2 shows measures of how extensively capital and labour were used by the two sets of countries in 2009. The median unsuccessful country benefitted from a somewhat larger labour input by employing a greater share of its population. The median successful one provided its workers with significantly more tools, as measured by the capital-to-GDP ratio. The median capital stock in the successful countries was about one-fourth larger, as a percent of GDP.

Figure 2

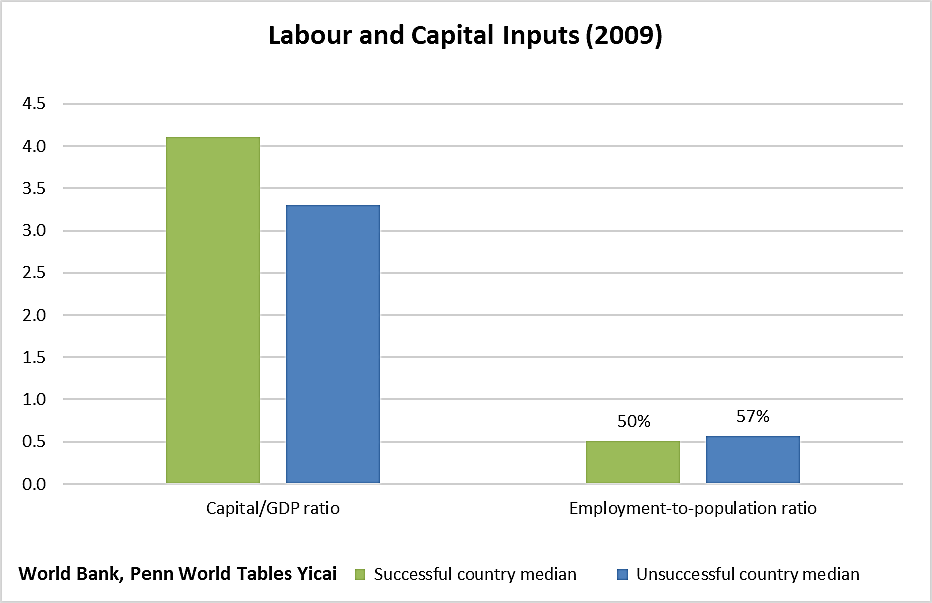

Economists have stressed that labour’s quality can be improved through education. Robert Barro made an important modification to the Solow model in showing the important role that “human capital” accumulation plays in the process of economic growth.

Figure 3 shows that the median successful country tended to invest more in education than its unsuccessful counterpart. In particular, the median successful country enrollment rate for tertiary education was close to double that of the unsuccessful country median. Thus, successful countries were able to compensate for their relatively low employment rates by investing in the education of their workers. The importance of human capital is good news for those countries that are undergoing demographic changes and are facing shrinking labour forces.

Figure 3

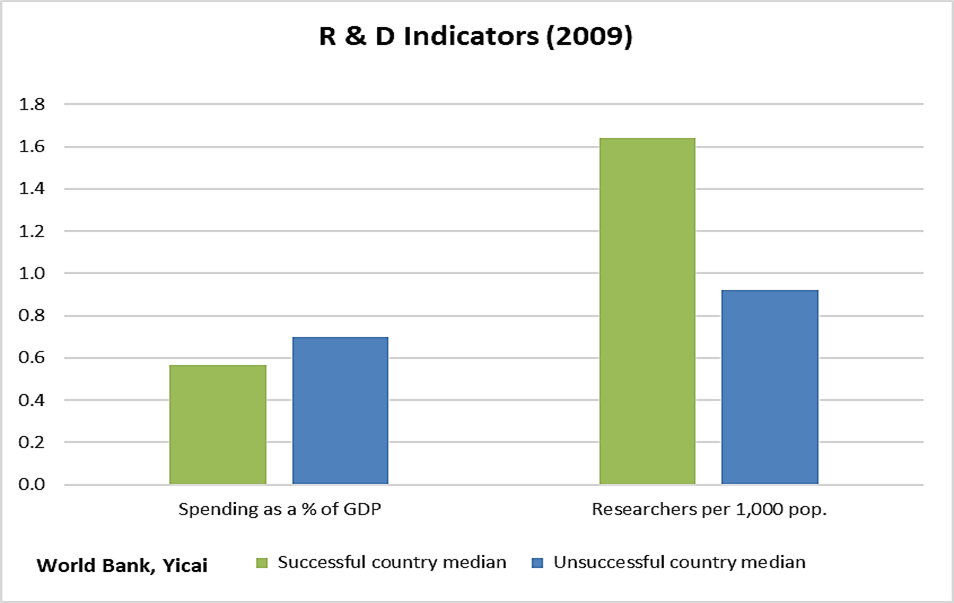

From the physical inputs of capital and labour, we now turn to productivity. There are two aspects to productivity. The first is improved technology, which is reflected in new products or better ways of doing things. Technological improvement often arises from investment in research and development.

Figure 4 presents two R & D indicators: spending as a percent of GDP and researchers per 1000 people. Surprisingly, unsuccessful countries spent 0.13 percent of GDP more on R & D than the successful ones. In contrast, the unsuccessful countries engaged only half as many researchers as their successful counterparts.

These indicators imply that technological improvement is, in essence, a human undertaking. The experience of the successful countries suggests that technological improvements are more likely to occur if R & D resources are spread widely.

Figure 4

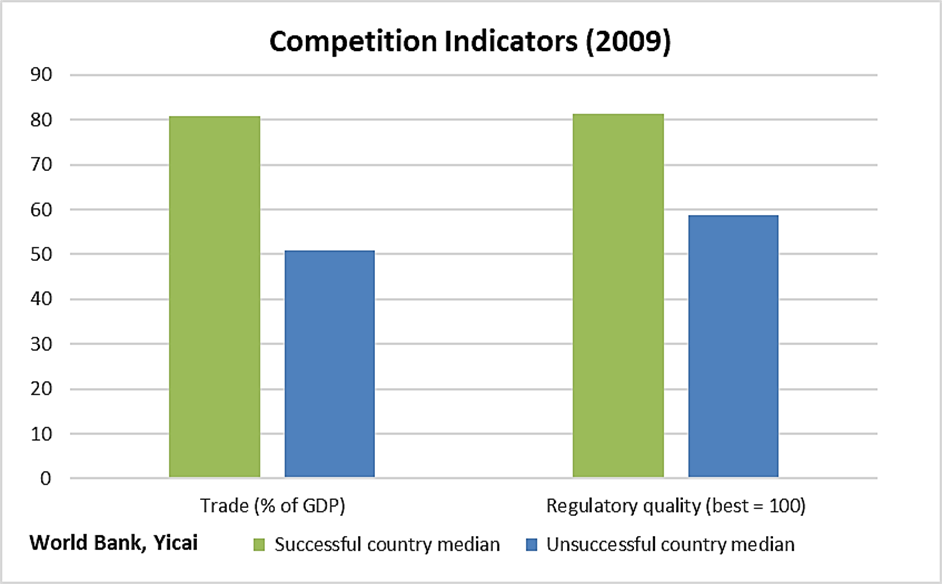

The second aspect of productivity is the set of incentives that lead participants in the economy to be as efficient as possible. These incentives arise through the establishment of effective institutions.

One such institution is openness to international trade. An open trading regime keeps import-competing firms on their toes and allows exporters to source inputs efficiently. Moreover, exporting firms that compete in the global marketplace have every incentive to produce first-class goods and services. Figure 5 shows that successful countries were more open to trade than unsuccessful ones. Their trade-to-GDP ratio was about 30 percentage points higher.

A second institution which acts to align incentives is a well-regulated domestic market. To operate efficiently, markets need clear rules that are consistently enforced. Intelligent regulation helps ensure that markets do not run amok. As Figure 5 shows, regulatory quality was higher in the successful countries, which likely improved the efficiency of their market outcomes.

Figure 5

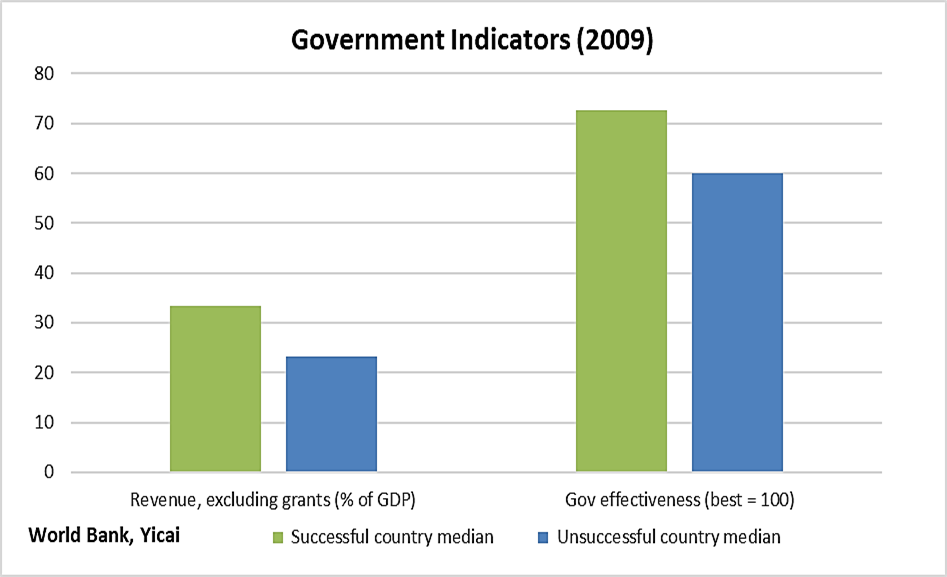

Governments are institutions which can provide the physical, legal and social frameworks to support high incomes. Harvard’s Ricardo Hausmann notes that “… a biomedical plant is more valuable if there is good infrastructure, a trusted drug authorization system, and health insurance. These inputs are deeply affected by government actions, embodied in millions of pages of legislation and thousands of government agencies.”

The effective provision of these frameworks requires stable sources of funding. Figure 6 shows that successful countries were better able to mobilize national revenue, which could be used for investing in public goods, health and education. Moreover, governments in successful countries were rated as more effective than those of the unsuccessful group, suggesting that the spending financed by this revenue was less likely to be wasteful.

Figure 6

Let’s take stock of the lessons suggested by the experiences of the successful countries. First, the accumulation of both physical and human capital is important. Second, R & D resources should be spread among an extensive group of researchers. Third, institutions matter. Domestic markets should be open to trade. They should operate within a high-quality regulatory system. Governments need access to sufficient funding to provide physical, legal and social frameworks and they should be highly effective to make sure these resources are well-targeted.

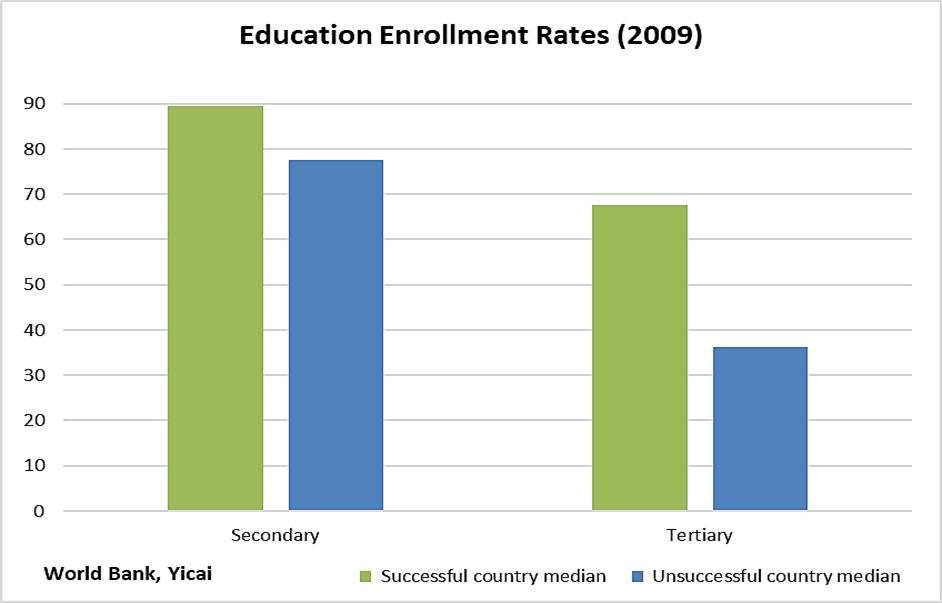

While China may be a decade and a half away from high-income status, it is not too early to see how it stacks up against those countries that avoided the middle income trap. Table 1 presents the most recent reading of the indicators discussed above for China and the two sets of countries. China does extremely well in mobilizing labor and physical capital. However, it is lagging somewhat on human capital. China is devoting significantly more financial and human resources to R & D. It lags on openness to trade and regulatory quality. While its government effectiveness rating is close to the successful country median, its government revenue-to-GDP ratio is close to the median of the unsuccessful group.

The extent to which the lessons of the ten successful countries can apply to China is limited. The Chinese economy is much larger and much less service-based than those of the countries we have been considering (Table 1). To some extent, China will have to make its own way to high-income status.

In a recent speech, President Xi said that it is “entirely possible” that China could double its per capita GDP and cross the high-income threshold by 2035. China’s per capita income is still a third below the successful country median. However, as Table 1 shows, it already exceeds the successful countries in a number of areas and appears to be off to a very good start to reaching high-income status.

Table 1