Checking in on China’s Private Sector

Checking in on China’s Private Sector(Yicai) Sept. 20 -- There is a narrative out there that blames some of China’s slower-than-expected recovery on private sector pessimism.

It draws on the large fines imposed on private sector giants: Alibaba and Meituan for anti-competitive behaviour, Didi for violating data security rules and Ant Financial for corporate governance and consumer protection infractions.

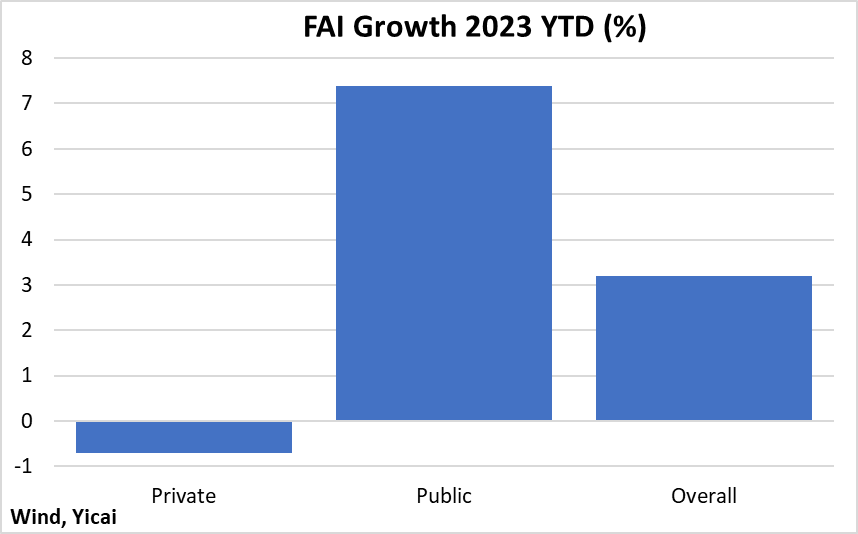

The narrative holds that private firms’ confidence has been eroded and their willingness to invest has fallen, contributing to the slow recovery. It points to the relatively poor performance of private sector fixed asset investment (FAI) in recent years. In the first eight months of this year, overall FAI rose by 3.2 percent while private sector investment fell by 0.7 percent. The private sector accounted for close to 52 percent of overall FAI this year. This implies that the growth of public sector FAI was 7.4 percent (Figure 1).

The narrative even suggests that China’s authorities do not really want a vibrant private sector.

Figure 1

Given how pervasive this narrative is, I believe it is a good time to look at some numbers and see how China’s leading private sector firms have been faring this year.

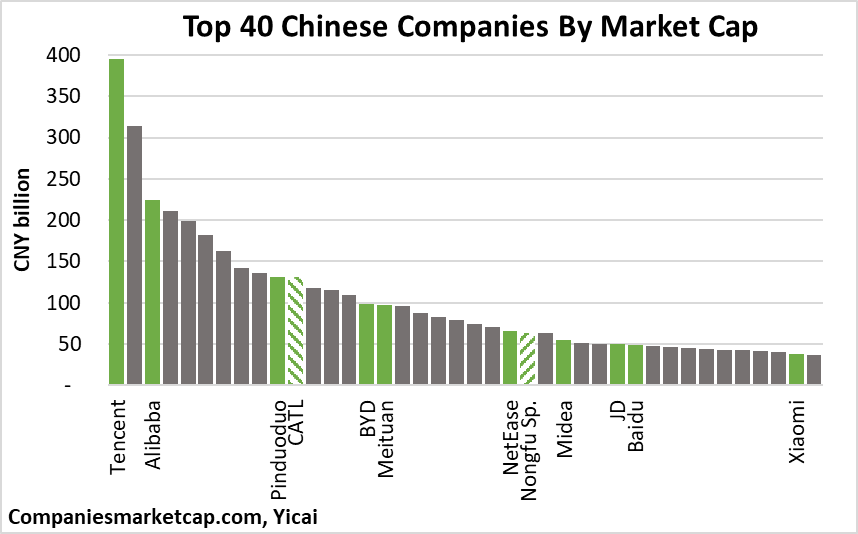

Figure 2 shows China’s 40 biggest companies in terms of stock market capitalization. To identify the private firms, I rely on the classification developed by Tianlei Huang and Nicolas Véron. They consider private enterprises as those in which the state’s ownership is less than 10 percent. There are twelve such firms in the top 40.

Five of the twelve firms – CATL (batteries), BYD (electric vehicles), Nongfu Springs (beverages), Midea (home appliances) and Xiaomi (electronics) – are manufacturers. Four – Alibaba, Pinduoduo, Meituan and JD – principally conduct e-commerce. NetEase and Baidu are internet companies. Tencent is China’s most valuable company. Its main business is gaming but it is also heavily involved in social media, entertainment and mobile payments.

Figure 2

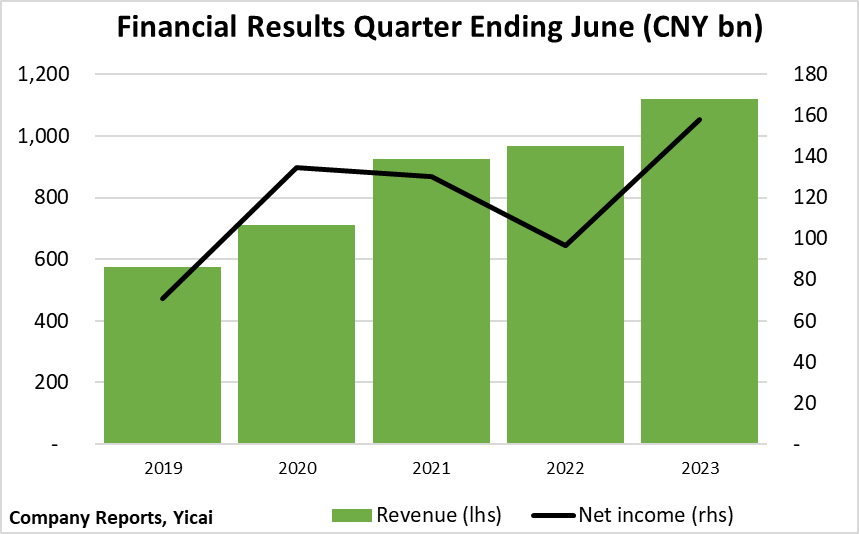

Ten of the twelve private companies have reported their operating results for the quarter ending June 2023 (I was unable to find the numbers for CATL and Nongfu Springs). These data allow us to see how well these large private firms are managing the challenging recovery and if they are facing undue difficulties.

In the quarter, aggregate revenue for the ten private companies reached CNY 1119 billion, up 16 percent from the April-June period in 2022 (Figure 3). Strong revenue growth this year is not surprising, given how weak the economy was last year. It is more impressive to consider that these companies’ revenues are almost twice as high as in the second quarter of 2019 since nominal GDP only rose by 28 percent over this period.

These firms’ profits (net income) growth has been even more rapid than that of revenues. They are up 124 percent from 2019 to CNY 158 billion. JD, Pinduoduo and Meituan – relative newcomers in the e-commerce space – registered very high rates of profit growth. The growth in BYD’s profits has also been spectacular. On the other hand, more established firms, like Tencent and Midea, only saw single-digit increases in profits.

Figure 3

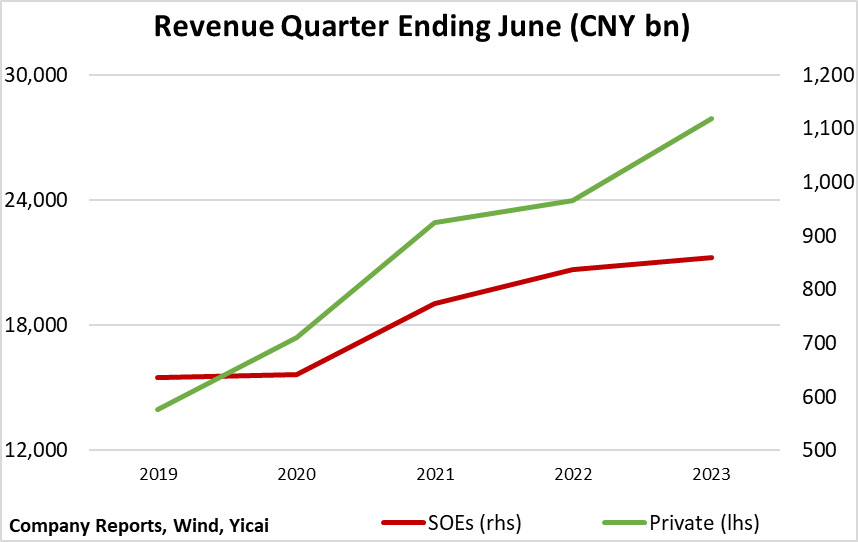

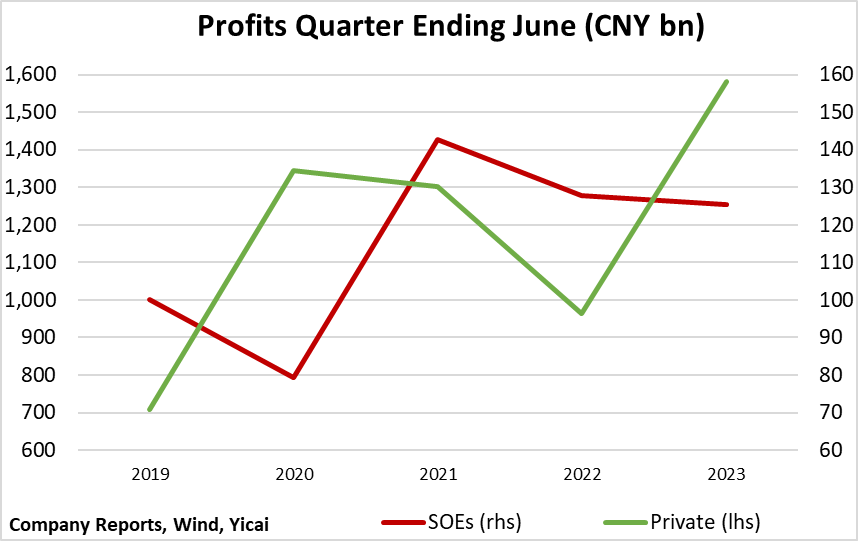

The performance of China’s largest private companies has been more impressive than that of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) both over the last year and since 2019.

SOEs’ revenues are only up 3 percent year-over-year and 37 percent since 2019. This is well below the 16 percent and the 94 percent recorded by the large private firms (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Similarly, while private firms’ profits rebounded by 64 percent in the second quarter, those of SOEs fell by 2 percent (Figure 5). SOEs’ profits have only risen by 25 percent since 2019, slightly slower than the growth of nominal GDP and significantly more slowly than those of the major private firms.

Figure 5

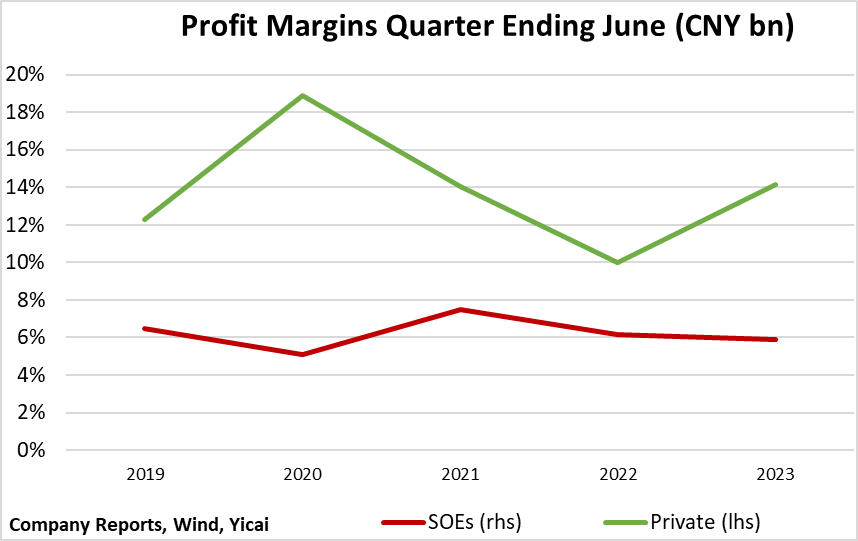

The gap in profit margins widened slightly from where it had been before the pandemic (Figure 6). The large private firms increased their margins by 2 percentage points whereas SOEs’ profit margins shrank by 0.6 percentage points.

Figure 6

I realize that I am not making apples-to-apples comparisons here. I am comparing the most valuable private sector companies with the “average” SOE. However, the narrative I have been alluding to suggests that it is those large and too-powerful private firms that have drawn the ire of the authorities. However, their financial data shows that China’s large private firms have been doing pretty well, all things considered.

At the same time, life has not been so easy for exporting firms or those which construct housing.

China’s recovery has been slower than expected because of shocks to exports and home construction. In the first half of the year, these shocks reduced GDP by 0.6 and 1.2 percentage points respectively. In other words, in the absence of these shocks, GDP growth in the first half would have been 7.3 percent instead of the 5.5 percent actually recorded. It turns out that the private sector’s participation in exports and home construction is very high.

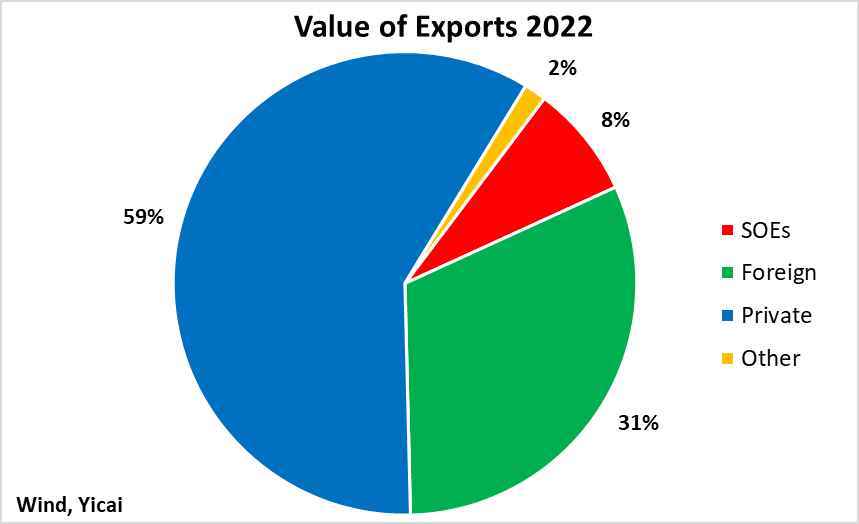

Data from China Customs show that domestic private firms accounted for 59 percent of the value of last year’s exports. Foreign firms accounted for 31 percent, SOEs for 8 percent and those of other ownership structures for 2 percent (Figure 7). This means that the effect of the decline in exports this year has fallen disproportionately on China’s private firms.

Figure 7

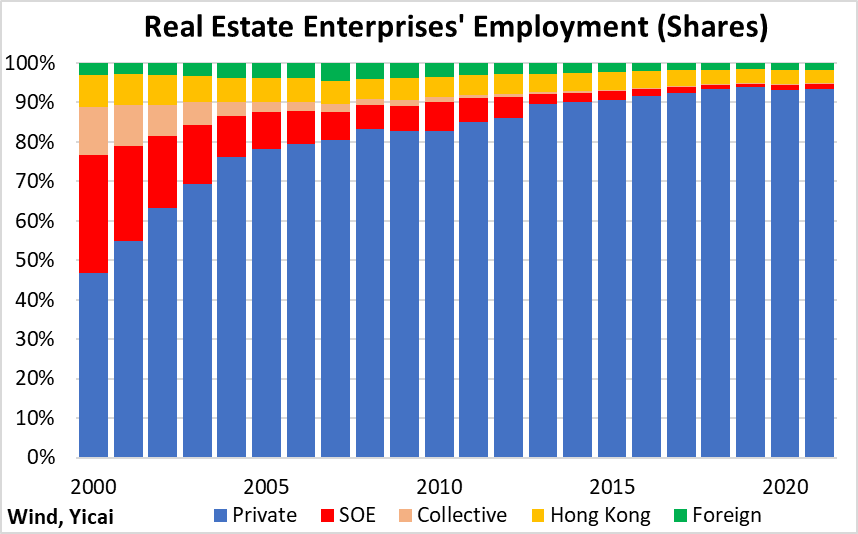

Similarly, data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) show that employment in the real estate industry is overwhelmingly in private firms (Figure 8). In 2000, the private sector only employed 47 percent of the workers in the real estate industry. By 2010, the share had risen to 83 percent and it stood at 93 percent in 2021. Here too, the sharp decline in housing has fallen disproportionately on private firms.

Figure 8

The downturn in the property market can explain a lot of the weakness in private FAI this year. At a recent press conference, remarks by NBS spokesman Fu Linghui suggested that real estate accounts for 36 percent of private FAI. In the first eight months of this year, real estate investment is down 9 percent. If we assume that private real estate investment fell by this amount as well, then non-real estate investment by the private sector must have been up by 4 percent. While this is certainly better than -0.7 percent, it points to a certain lack of confidence in the recovery among entrepreneurs.

The government has taken notice of the private sector’s challenges.

On July 19, the Party and the State Council jointly issued a set of 31 guidelines to boost the growth of the private economy, by promising to improve the business environment, enhance policy support and strengthen the legal guarantees for its development.

On September 4, it was announced that a bureau would be set up under the National Development and Reform Commission to analyze the evolution of the private economy and formulate policies to promote its development.

The situation of China’s private sector is more complex than simple narratives would have us believe. And nothing beats a good look at the data to clear away misconceptions. Hopefully, the government’s supportive policies will further catalyze private sector confidence and lead to more rapid rates of investment going forward.