Can China be the Next Korea?

Can China be the Next Korea?(Yicai Global) March 30 -- As part of this month’s Two Sessions, China released the final version of its 14th Five-Year Plan. These planning documents outline the government’s medium-term strategic thinking. They are required reading for those who want to know where the leadership wants to take the country. I think the 14th Five Year Plan is particularly important because it represents a turning point in China’s economic development.

For close to 40 years, one of China’s key development objectives was the creation of a moderately prosperous society (小康社会). It was a policy first enunciated by Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s. Deng borrowed the term from the Confucian classic the Book of Rites (礼记), which is believed to have been compiled in the Han dynasty, more than 2000 years ago.

In its original context, the moderately prosperous society is presented as a somewhat second-rate state of affairs. It is unfavourably contrasted with the utopian great community (大同). However, Deng’s choice was intentional. In creating his development plan, he wanted to set a low bar so as not to feed .

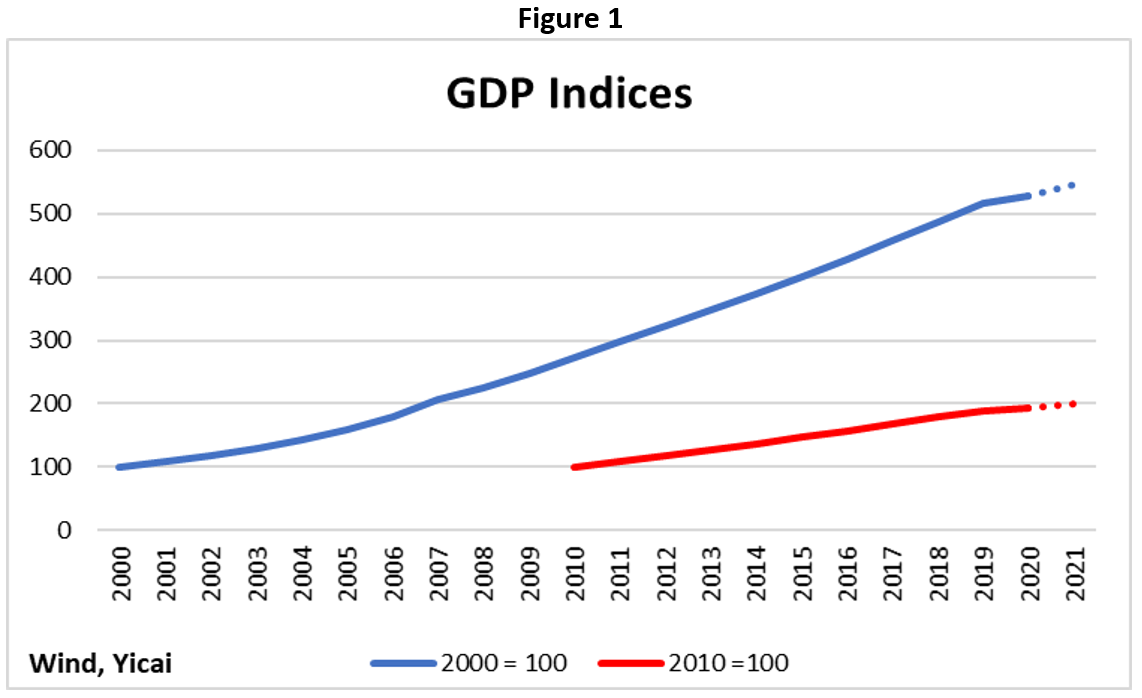

Deng’s vision was a qualitative one. Chinese society would, over time, evolve from scarcity to relative comfort. Deng’s successor, Jiang Zemin, went a step further, operationally defining the moderately prosperous society as a between 2000 and 2020. That target implied average real GDP growth of just over 7 percent per year for two decades. In the event, growth was significantly higher during Jiang’s tenure and that of his successor Hu Jintao. After Xi Jinping took office, growth continued to exceed 7 percent and, by 2015, GDP was essentially four times higher than in 2000 (Figure 1).

In 2013, Xi Jinping associated the establishment of a moderately prosperous society with a doubling of GDP between 2010 and the celebration of the Party’s 100th anniversary in 2021. He recently that he expects that doubling to be achieved later this year. Indeed, given the government’s 6 percent plus growth target, we should reach moderate prosperity sometime this summer (Figure 1).

China’s moderately prosperous society will be characterized by a reasonable standard of material well-being. In 2000, its per capita GDP (PPP basis) ranked in the bottom third of all countries. By 2020 it ranked in the top 40 percent. While China does exhibit a high degree of income inequality, the work done to last year shows the efforts made to ensure that the fruits of growth were shared with the least fortunate.

With the moderately prosperous society established, the 14th Five-Year Plan ushers in a new stage in China’s economic development: building a modern socialist country. With a basic level of material comfort achieved, a greater stress will be put on environmental remediation and green growth. Aggregate demand will increasingly rely on a robust domestic market. And innovation will become a driving force for development.

It is easy to see why the 14th Five-Year Plan emphasizes innovation. China’s working age population is shrinking. Its investment rate is already very high and the rapid increase in debt in recent years limits how much more capital accumulation can contribute to growth. This leaves increasing productivity as the most rational way to develop.

So, how innovative is China?

While innovation is hard to measure, Bloomberg has, for some time, published an index that tries to cut into this question. The index is a weighted average of seven elements.

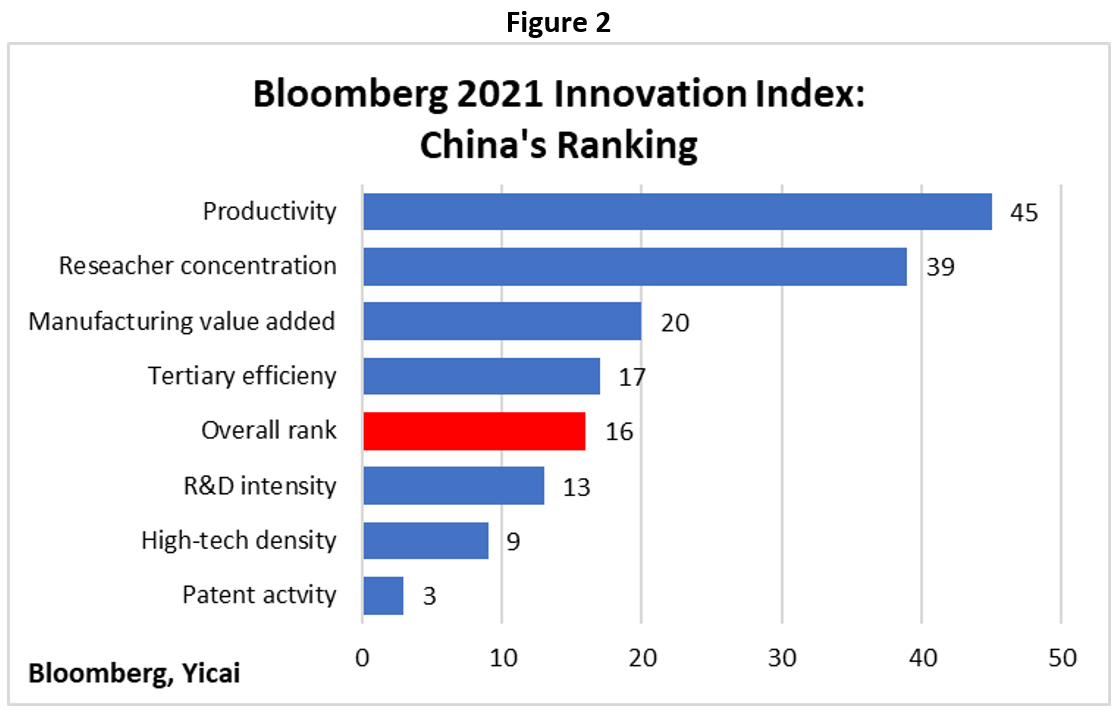

China ranked 16th out of 60 countries in the of Bloomberg’s index: just ahead of Ireland and behind Norway. It’s a pretty good result, considering China is not nearly as rich as its European “neighbours”.

The individual elements of Bloomberg’s index suggest the areas in which China might want to work, in order to increase its ability to innovate.

Figure 2 shows China’s ranking on each of the seven components, along with its overall rank. China does well on patent filings, creating high-tech companies and spending on research and development.

Its weak spots are productivity and researcher concentration.

China ranked 45th on productivity, which considers the level and change of output per employed person.

China ranked 45th on productivity, which considers the level and change of output per employed person.

China’s poor performance here echoes the made by Miao Wei, the former Minister of Industry and Information Technology. Miao said that China is at least 30 years away from achieving its goal of becoming a strong manufacturing power.

If we compare China’s manufacturing sector with that of the US, we do, indeed, find a large productivity gap.

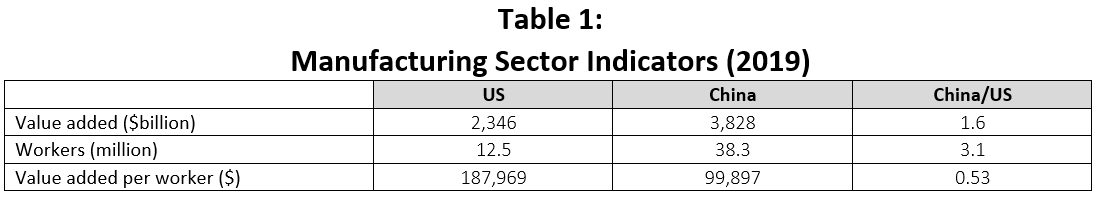

Table 1 shows that the value added of China’s manufacturing sector was 1.6 times as large as the US’s in 2019. However, that output was produced by more than three times as many workers. So, the productivity of China’s manufacturing sector – in terms of value added per worker – was only half as high as the US’s.

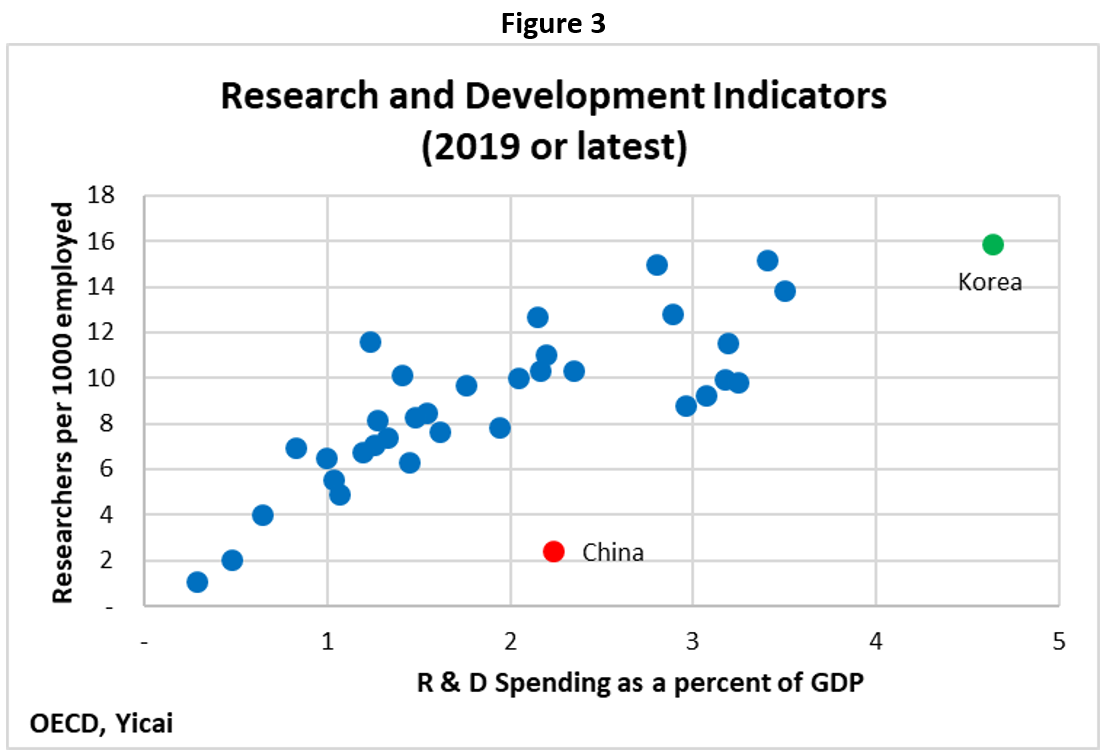

China spends a lot on research and development but it is less successful on the human resources side. Bloomberg ranked it 39th in the employment of researchers (as a share of the workforce). Based on the experience of other countries, China should be engaging five times more researchers than it currently does, given its research and development expenditures (Figure 3).

China spends a lot on research and development but it is less successful on the human resources side. Bloomberg ranked it 39th in the employment of researchers (as a share of the workforce). Based on the experience of other countries, China should be engaging five times more researchers than it currently does, given its research and development expenditures (Figure 3).

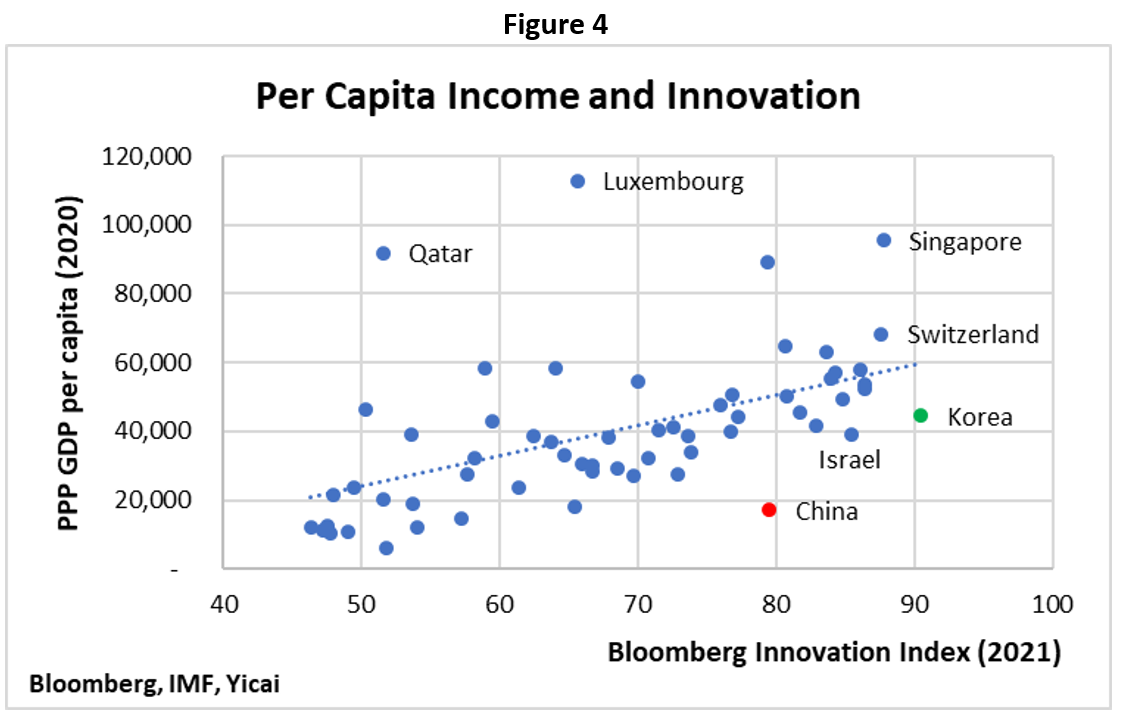

Figure 3 also shows that Korea is an outlier both in terms of how much its spends on research and development and the number of researchers it engages. It will come as no surprise, then, that Bloomberg ranked Korea as the world’s most innovative country. Korea’s achievement – like China’s – is noteworthy because its innovation ranking is much higher than one would expect given its per capita income (Figure 4).

Figure 3 also shows that Korea is an outlier both in terms of how much its spends on research and development and the number of researchers it engages. It will come as no surprise, then, that Bloomberg ranked Korea as the world’s most innovative country. Korea’s achievement – like China’s – is noteworthy because its innovation ranking is much higher than one would expect given its per capita income (Figure 4).

How do we explain Korea’s success in innovation and what lessons might it hold for China?

How do we explain Korea’s success in innovation and what lessons might it hold for China?

There are three aspects of the Korean model that stand out.

First, Korean firms are large, they have significant resources and can quickly scale up new products. This is especially true of Korean conglomerates – the chaebols. Perhaps because of their scale and dominant market positions, firms play a much larger role in funding research and development in Korea than businesses in other countries. While the government supports investment in research and development through tax credits, it also makes sure domestic firms are subject to the discipline of competition.

Second, there is close collaboration between government and business. The government facilitates innovation by engaging in targeted programs. In the mid-1990s, it invested to build up the country’s . More recently, it announced a , which will create smart hospitals and digital management systems for traffic, water resources and disaster response. Working with the chaebols, the government has developed a number of innovation centres in an effort to create industrial clusters.

Third, Korea puts a high premium on creating and attracting human capital. Close to 70 percent of Koreans between the ages of 24-34 have tertiary education. This is well above the OECD average of 45 percent and the highest among all countries surveyed by the OECD. Korea has also Korean academics who studied abroad.

Korea’s firms have emerged as world leaders in memory chips, cellphones, and liquid crystal displays. Moreover, its innovative cultural industry is having a world-wide impact. K-pop is a global phenomenon. Korean TV dramas are all the rage here in China. My wife was crazy about My Love from the Star (来自星星的你). And movies like have received critical acclaim internationally.

A friend of mine, who served as a diplomat in Seoul, describes Korea’s experience with innovation as comprising three phases: imitation, continuous improvement and ground breaking invention. And Koreans describe themselves as moving from “fast-followers” to “pace-setters”.

China is squarely in the continuous improvement phase. A lot can be achieved here. Indeed, the Korean experience suggests that successful innovation, at this level, offers considerable scope to avoid the middle-income trap.