Is the Worst in US-China Relations Behind Us?

Is the Worst in US-China Relations Behind Us?(Yicai Global) June 9 -- I want to go out on a limb and make a prediction. I think that US-China relations have hit bottom and that we will see a modest improvement from here on in.

I am basing my forecast on the recent video call between Vice Premier Liu He and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and the phone call between Liu and Trade Representative Katherine Tai. Apparently, the calls were cordial and both Ms. Yellen and Ms. Tai looked forward to further discussions with Mr. Liu.

There have always been cycles in the US-China relationship. I attribute this, on the American side, to an ongoing tug-of-war between two factions: the security establishment and the broader business community.

In the US, the security establishment has traditionally played an outsized role in formulating foreign policy. Sixty years ago, in his farewell address, President Eisenhower admonished Americans to “… guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

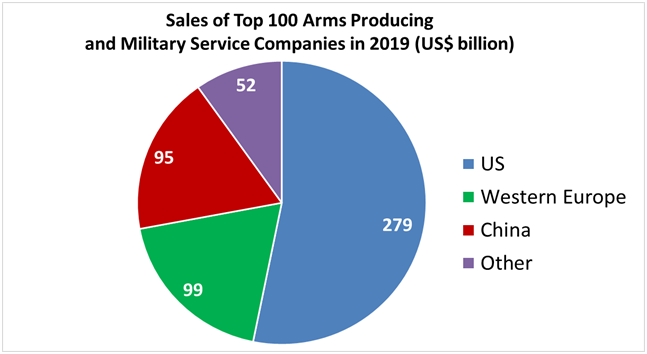

How powerful is this military-industrial complex? One way to gauge its influence is arms sales. US firms accounted for more than half of the world’s sales of arms and military services in 2019 (Figure 1). This was more than twice the US’s share of global GDP.

Figure 1

Since the US government is its major client, the American arms industry has a clear incentive to promote the view that the US’s security is at risk. For thirty years following President Eisenhower’s speech, that threat came from the Soviet Union. Then it came from Iran. Then from Iraq. Then from al-Qaida. With the Trump Administration, the focus shifted to China.

In its most recent Annual Threat Assessment, the US Intelligence Community said, “China increasingly is a near-peer competitor, challenging the United States in multiple arenas—especially economically, militarily, and technologically—and is pushing to change global norms.”

What kind of military threat does China really pose to the US?

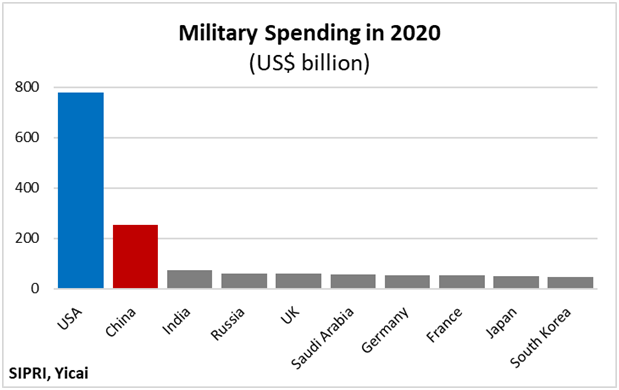

Looking at the numbers, it is hard to see China challenging the US’s supremacy. Figure 2 shows that the US spends three times more on its military than China does. Even after adjusting for lower prices in China, Chinese military expenditures are only 53 percent of what they are in the US.

Figure 2

Over the years, the US has built up an overwhelming advantage in military hardware.

In its report on China’s military, the US Defense Department stated that China plans to double its nuclear warhead stockpile – “currently estimated to be in the low-200s” – over the next decade. The US’s own nuclear stockpile is estimated to be around 3,800 warheads, or 9.5 times what China might achieve by the decade’s end.

The US has 11 aircraft carriers, while China only has two. The US has four times as many military aircraft as China. And so on.

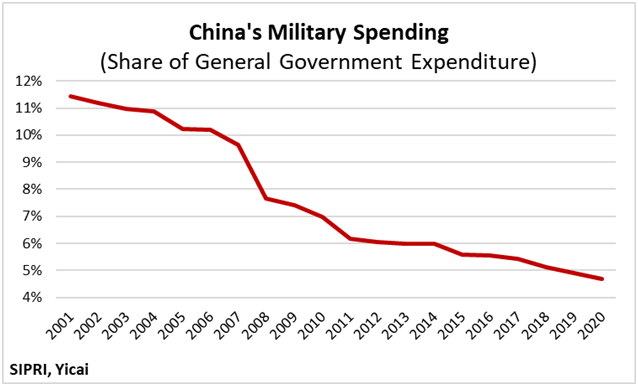

Not only is China far behind the US in current military capability, but the profile of Chinese government spending does not suggest that it is in the midst of an arms race. Figure 3 shows that military spending, as a share of general government spending, has fallen from over 10 percent in the early 2000s to under 5 percent last year. Military spending accounted for just under 8 percent of US government spending in 2020.

Figure 3

Does China pose an economic and technological threat to the US?

It is true that China’s economy is poised to overtake the US’s as the world’s largest sometime toward the end of the decade. Moreover, innovation will play a greater role in China’s economic development.

Nevertheless, US per capita incomes are four times higher than those in China (in purchasing power parity terms) and the productivity of China’s manufacturing sector is only about half as high. So, even if China is developing quickly, it will take generations before it catches up with the US.

The more important point is that China’s development is not a “zero sum game”. China is deeply embedded in the global economy. Notwithstanding the political frictions, Nike, Disney, Starbucks and the NBA remain extremely popular here, illustrating how the US benefits from China’s rise.

This is what the broader US business community sees. It understands the high cost of being cut out of China’s growing markets – both in terms of lost sales and the inability to spread the costs of R&D over a larger customer base. The ongoing opportunities in China is what drove BlackRock and Goldman Sachs to announce new wealth management joint ventures and JPMorgan to take full control of its securities JV.

The broader US business community also knows that import barriers raise costs and reduce their competitiveness. This is why 3700 US companies, including Ford, Tesla, Walmart, and Coca-Cola have challenged the legality of the tariffs imposed by the Trump Administration on China.

I believe that we are at a turning point. President Biden’s new budget reflects the priorities of a less hawkish administration, suggesting the influence of the security establishment is waning. By investing heavily in infrastructure, education and R&D, it represents a sharp change from the concerns of the Trump Administration.

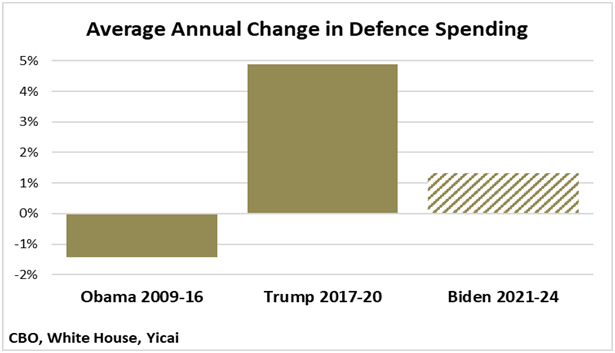

In part, because of this reorientation of priorities, military spending is being squeezed out. Following many years of decline during the Obama Presidency, defence spending grew by 5 percent per year under the Trump Administration. President Biden is budgeting for defence spending to only grow by 1.3 percent per year over the next four years (Figure 4).

Figure 4

President Biden’s emphasis on repairing domestic deficiencies, while keeping military spending below the rate of inflation bodes well for US-China relations.

While I expect the two countries to become more cooperative, it may take some time for the rhetoric to cool off. Neither side will want to be seen as soft on the other.

For example, President Biden’s recent executive order prevents Americans from investing in 59 Chinese companies which “undermine the security or values” of the US and its allies. This is clearly a rhetorical rather than a material development.

Given China’s huge pool of domestic savings, the ban will have no effect on these firms’ cost of capital. Moreover, for Americans who want to invest in China’s development, it clarifies that owning shares in the remaining pool of Chinese listed companies is not unpatriotic.

While President Biden’s executive order may make headlines, I believe the recent calls between top American and Chinese officials will actually bring us one step closer to President Eisenhower’s vision “… that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.”