Are Foreign Investors Deserting China?

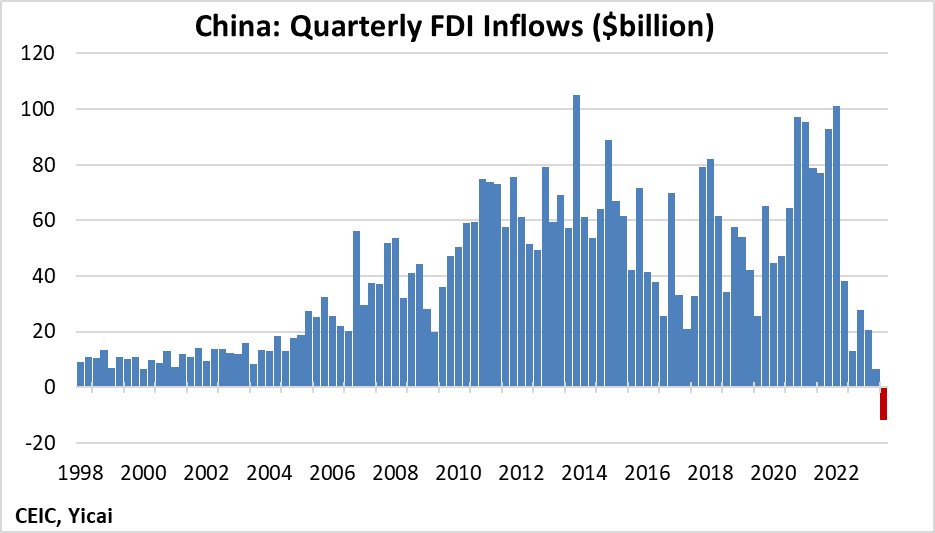

Are Foreign Investors Deserting China?(Yicai) Nov. 13 -- On November 3, China’s State Administration for Foreign Exchange released the for the third quarter. Most eye-catching among the statistics was the USD11.8 billion decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows. As one of the world’s top destinations for foreign direct investment, China typically has recorded large quarterly increases in FDI and the drop observed in Q3 was the first since the series began in 1998 (Figure 1).

Figure 1

In contrast to “portfolio” investment, which refers to the cross-border purchase of stock and bonds, FDI when an investor establishes a lasting interest in and significant degree of control over an enterprise in another country. FDI is important because it is seen as creating stable, enduring links between economies.

China does not depend on FDI to finance its development. For example, FDI totalled USD187 billion in 2019 when domestically sourced investment exceeded USD6 trillion. Rather FDI is important because it represents a channel by which knowhow, in the form of best international practice, is transferred to Chinese firms. Moreover, openness to FDI is one way of enhancing the competitiveness of domestic enterprises.

Some observers are that Q3’s foreign investment outflow is a sign that de-risking or friend-shoring is for real.

So, are foreign investors deserting China?

While Q3’s FDI decline could indicate that some foreign investors are selling their businesses and returning home, it is more likely that the unprecedented fall points to their decisions to repatriate profits or repay loans to their overseas headquarters rather than re-invest in their China operations.

As always, it is important to compare China’s experience with those of other countries. So, it is worth noting that China is not alone, among major economies, in facing FDI outflows this year.

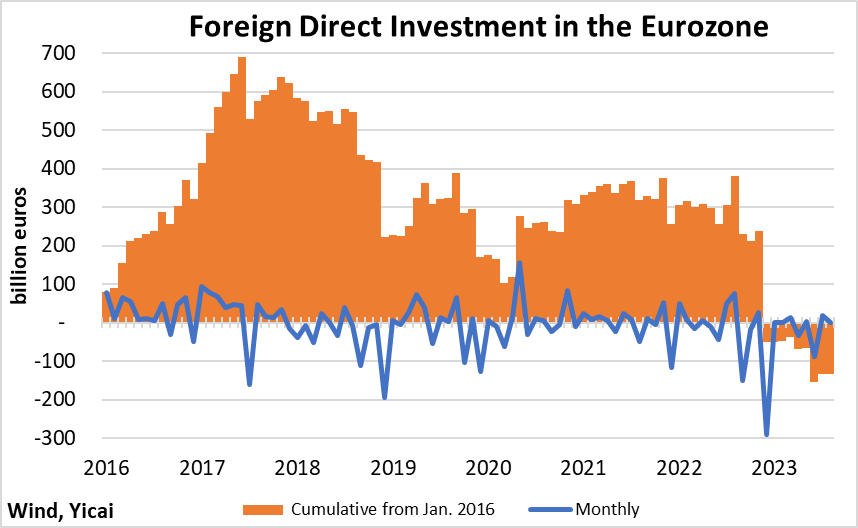

Figure 2 presents the monthly FDI flows into the Eurozone from January 2016 through August 2023. The data are volatile with frequent monthly decreases. To clarify the longer-term trend, Figure 2 also presents the cumulative FDI flow since January 2016. Cumulative FDI has declined steadily since peaking at close to 700 billion euros in June 2017. However, the drop this year has been especially sharp with cumulative flows falling some 370 billion euros since November 2022.

Figure 2

While it could be the case that foreign investors are de-risking their exposure to Europe as well, it is also possible that both China and the Eurozone are being affected by the same global financial trend.

Investors consider a broad set of fundamental factors before deciding to make a cross-border acquisition including the target country’s market size, its political and macroeconomic stability, potential GDP growth, the regulatory environment and the ability to repatriate profits.

In addition, the difference between the investment’s projected rate of return and the risk-free rate – the project’s “excess return” – is an important consideration in deciding whether or not to invest overseas.

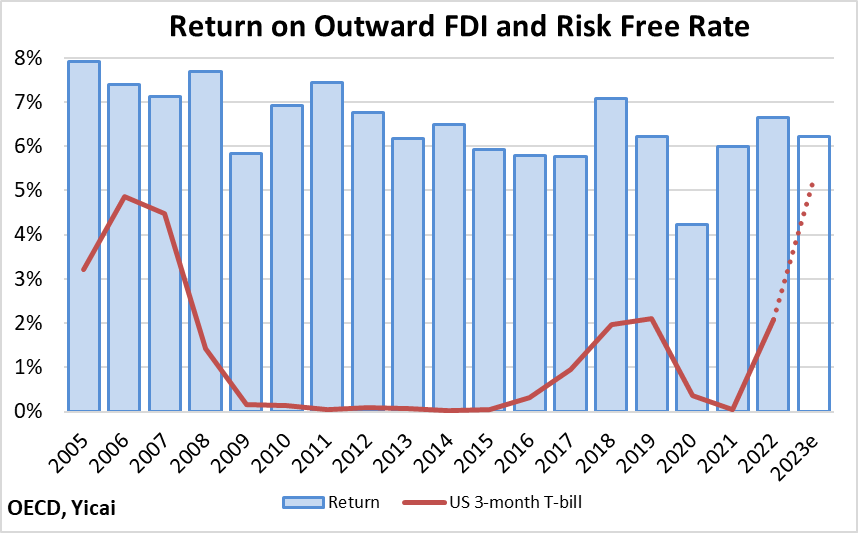

The actual return on FDI made by OECD countries has drifted down over time (Figure 3). Before the global financial crisis, returns exceeded 7 percent. During the pandemic years, they fell to less than 6 percent. Very low risk-free interest rates (proxied here by yields on three-month US Treasury bills) provided a powerful incentive to invest following the global financial crisis. However, as rates have risen to rein in inflation, that calculus has changed.

So far this year, the risk-free rate has averaged 5¼ percent, up from just over 2 percent in 2022 and zero percent in 2021. We do not know how the return on FDI will turn out this year. But we do know that the IMF’s most recent World Economic Outlook (WEO) projects global growth to be 3 percent this year and 2.9 percent for 2024. These rates are well below the 2005-19 average of 3.7 percent. To be optimistic, let’s assume that the rate of return on FDI will come in at 6.2 percent this year – the same rate as achieved in 2019.

Figure 3

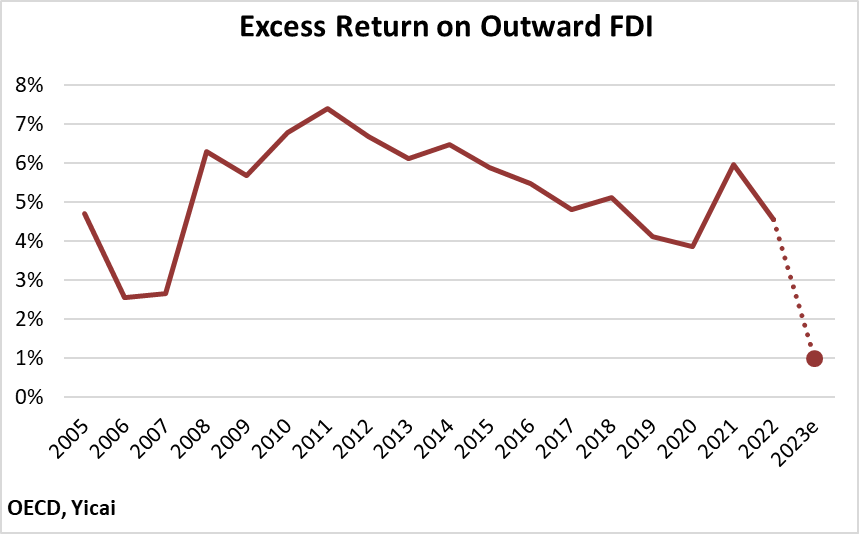

Given 6.2 percent for the rate of return on FDI and assuming that the risk-free rate remains at 5¼ percent for the rest of the year, the “excess return” on FDI will fall to 1 percent. This would be, by far, the lowest “excess return” recorded in recent years (Figure 4). It is very possible that at 1 percent, investors feel that the return on cross-border investment does not justify the risks involved and this is what explains the FDI outflows in both China and the Eurozone.

Figure 4

Berkshire Hathaway’s most recent quarterly report also shows the effect of rising interest rates on investment decisions. Berkshire’s cash holdings rose to a record USD157 billion in Q3, up USD10 billion from the previous quarter. While we are not talking about FDI here, most of Berkshire’s investments are in the US, Warren Buffett is also sensitive to the difference between the risk free rate and what he can expect to earn by buying stocks. For the in more than 20 years, the rate on three-month Treasury bills was higher than the S&P 500’s trailing earnings yield. This, no doubt, influenced Buffett’s decision to hold a greater portion of his assets in cash.

I predict that it won’t be long before China’s FDI account begins to post inflows again. It seems possible that interest rates in the US have peaked. In fact, the market predicts that the Fed Funds rate will fall by 75 basis points in 2024. More importantly, it appears that, following the release of the better-than-expected Q3 national accounts, we will see renewed optimism about China’s economic prospects.

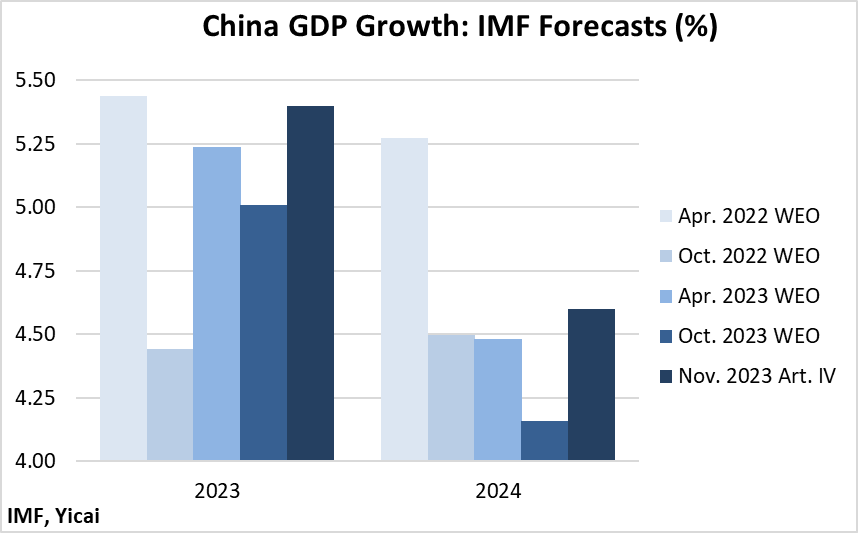

The IMF’s of China’s GDP growth for 2023 and 2024 is a good example of this turnaround in sentiment. With the completion of its 2023 Article IV mission, the Fund’s staff raised its outlook for growth this year to 5.4 percent. This is up from 5.0 percent in its October 2023 WEO and a full percentage point higher than in the October 2022 WEO. The staff now see growth next year coming in at 4.6 percent, up from 4.2 percent in October (Figure 5).

Figure 5

I am skeptical that supply chain de-risking poses a macroeconomic challenge for China. Some firms will certainly decide to find secondary sources of supply for elsewhere. Nevertheless, I believe that China will continue to be an attractive destination for foreign investment for the following three reasons.

First, China’s deep expertise in manufacturing means that it has created an ecosystem in which component parts can be easily found or developed. It would be prohibitive to re-create this ecosystem in countries with much smaller manufacturing bases.

Second, compared to the ASEAN countries, Mexico and India, China has superior logistics, a better educated workforce and superior intellectual property protection ().

Third, China’s growing consumer market exerts considerable economic gravity on firms’ decisions of where to locate.

Economists have a saying, “One data point does not make a trend.”

While I believe that the decline in China’s FDI inflows is unlikely to persist, given FDI’s importance, the attitudes of foreign firms toward the China market are certainly worth watching closely.