China’s Accession to the CPTPP: A Golden Opportunity

China’s Accession to the CPTPP: A Golden Opportunity(Yicai) Aug. 14 -- Last month, the United Kingdom formally agreed to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). The CPTPP is a free-trade agreement created by the eleven remaining members of the ill-fated Trans-Pacific Partnership from which the US withdrew in 2017. Once its Parliament ratifies the Agreement, the UK will join Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam in the trading block.

A half-dozen other countries have also applied to join the CPTPP, with China’s application having been the earliest received.

Joining the CPTPP would produce significant economic gains for China and its trading partners. According to China’s Deputy Minister of Commerce, Wang Shouwen, the CPTPP will help deepen domestic reforms and accelerate high-quality development. Moreover, by further opening up and expanding access to the world’s second-largest economy, the benefits of China’s joining the CPTPP will be shared broadly among its member-countries.

The process of China’s joining the CPTPP will be complex and time-consuming. Still, by renewing China’s terms of economic engagement with the rest of the world, it has the potential to address some of the concerns raised by China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO). It, therefore, has the potential to help diffuse the China-US trade tensions that have poisoned the global trading system.

Before assessing China’s prospects to join the CPTPP, it would be worthwhile to review its experience under the WTO.

It took 15 years of negotiations before China joined the WTO in 2001. This was 5 more years, on average, than it took those countries which joined after 1995. China’s commitments and concessions were much deeper than those made by almost all other WTO members. Key protections for China’s trading partners included (i) permitting them to impose tariffs or quotas if Chinese imports disrupted their domestic producers, (ii) the right to apply non-market economy status when calculating anti-dumping duty rates on Chinese imports and (iii) limits on the growth of Chinese textile and apparel exports.

Tan discusses the “seismic shift” that joining the WTO entailed for China. Following its accession, China made large cuts to import tariffs and liberalized its rules around trading licences to introduce private and foreign competition. In addition, the government undertook “a formidable legislative and regulatory overhaul” to bring domestic laws and policies into compliance with the international trading system.

China’s leaders believed that further integration with the rest of the world was the best way to increase economic efficiency and raise people’s standard of living.

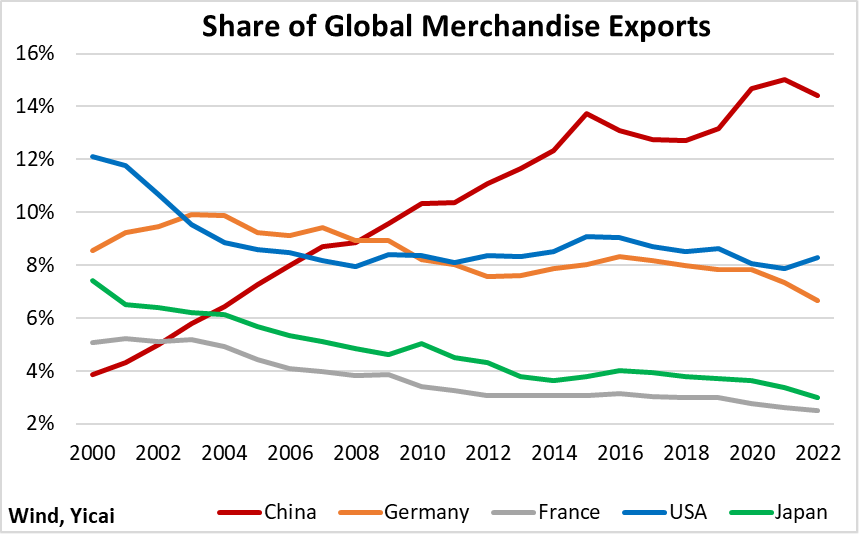

Brandt and co-authors document the ways in which trade liberalization improved the productivity of China’s manufacturing sector. The upgrading of China’s manufacturing sector is reflected in the rapid rise of its share of global manufacturing exports. Prior to China’s accession to the WTO, its merchandise exports accounted for 4 percent of the world’s total. By 2009, China had surpassed Germany as the world’s largest exporter, with a 10 percent share (Figure 1). In recent years, China has accounted for more than 14 percent of global exports, the same share as the US had in the early 1960s.

Figure 1

Some see the rapid advance of the Chinese economy as the result of unfair trading practices. For example, in 2018, the US Trade Representative’s report to Congress stated that “the United States erred in supporting China’s entry into the WTO on terms that have proven to be ineffective in securing China’s embrace of an open, market-orientated trade regime.”

Has China abided by the WTO’s rules?

The WTO provides a mechanism for concerns about unfair trade practices. Complaints are assessed in an even-handed and transparent manner. According to trade policy experts Baccus and co-authors, “reviewing the cases brought against China makes clear that China’s track record in WTO compliance is actually quite good.”

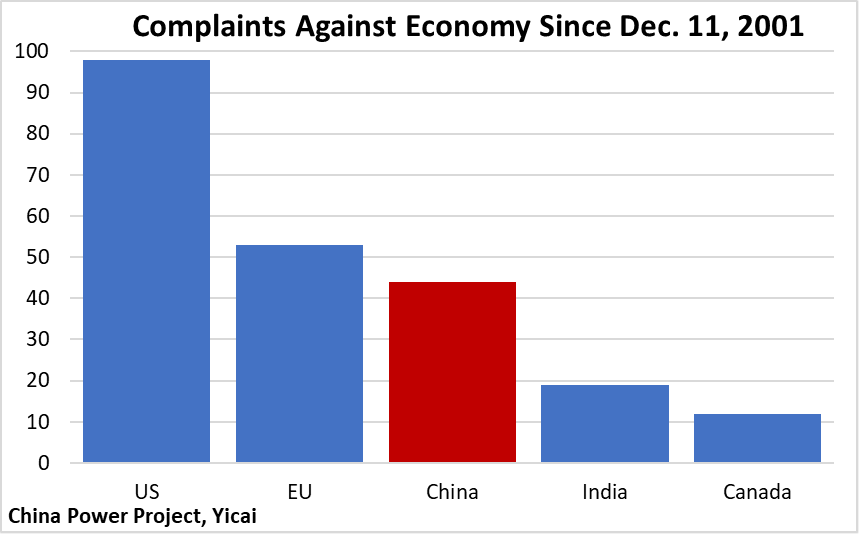

Between its accession to the WTO in late 2001 and 2019, WTO members made 44 complaints against China’s trading practices (Figure 2). This was slightly less than the 53 made against the EU countries and less than half the amount made against the US. Given the scale of its international trade, it suggests that China’s trading practices were not particularly egregious.

Figure 2

According to a report by the European Parliamentary Research Service, in those instances where the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism ruled against it, China “faithfully complied with WTO rulings in a timely way, in contrast with the at times considerably delayed or even refused compliance by other major WTO members, such as the EU and the USA.”

Even if China abided by the WTO’s rules, could the US’s frustration with its accession be justified by the dislocation it caused to US workers?

Trade liberalization creates winners and losers. While the winners are a diffuse group that benefits moderately from increased access to goods and services, the losers are typically much more concentrated, affected more deeply and better able to motivate a political response.

A study by Jaravel and Sager attempts to quantify the gains and losses to US households of China’s accession to the WTO. Their analysis shows that increased trade with China increased each US household’s annual purchasing power by USD1,500. In sum, more intensive trade with China raised the total purchasing power of US consumers by USD411,464 for each displaced job, the annual salary of which averaged USD40,000. The authors’ findings imply that the overall gains to US consumers through lower prices were more than enough to compensate all US workers who lost their jobs due to increased competition from China.

If China’s accession was both good for China and good for the US, why do some Americans consider it a mistake?

I think that there was a misconception that WTO accession would transform China’s economy into something that was very much like the US’s. However, Long Yongtu, China’s Chief Negotiator during its WTO accession process has said, “When we promised to adopt a market economy, we made it absolutely clear that it would be a socialist market economy. But others couldn't figure out why it was necessary to add "socialism" or how it would make a difference.”

Industrial policy and state-owned enterprises will play a much larger role in China than they do in most Western economies. The key is to demonstrate that a socialist market economy can be consistent with fair trade. This is where the CPTPP comes in. It is seen as a “next-generation” trade agreement. It takes WTO rules further in several key areas, such as digital trade and electronic commerce, intellectual property and state-owned enterprises.

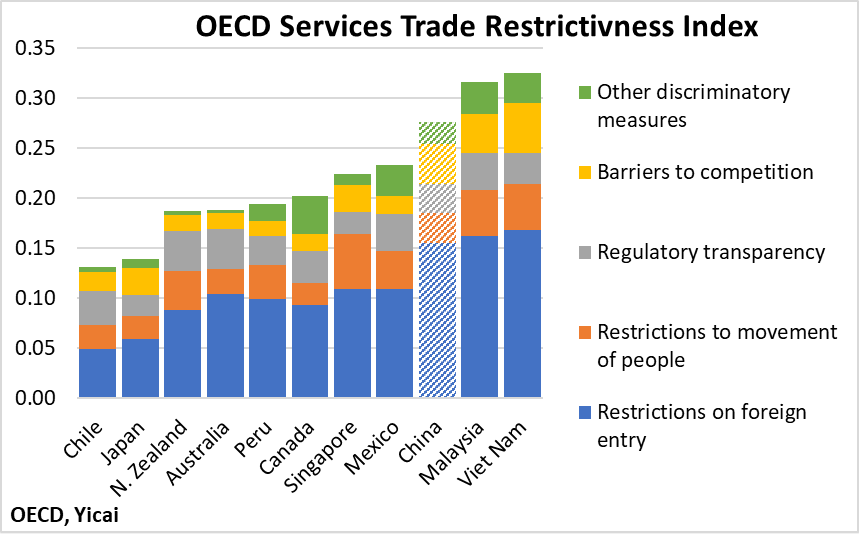

If China joins the CPTPP, the service sector is the one in which Chinese consumers can expect the biggest benefits. According to Wang Shouwen, China has “basically opened its doors to foreign investors in the manufacturing sector, and the service sector will be gradually opening up.” As Figure 3 shows, China’s service sector is less open to trade than those of most CPTPP countries but is more open than those of Malaysia and Viet Nam (the OECD does not provide data for Brunei). The CPTPP takes a “negative list” approach. This means that all services sectors are considered open to foreign participation unless they have been covered by explicit exemptions.

Figure 3

The CPTPP’s chapter on state-owned enterprises establishes rules to promote fair competition and prevent market distortion by governments. Governments preserve the right to pursue public policy objectives through the operation of state-owned enterprises but the rules are designed to ensure that these enterprises do not unduly distort international trade.

According to Weihuan Zhou, the CPTPP’s rules on state-owned enterprises are actually less restrictive than the obligations that China undertook when it acceded to the WTO. Moreover, Mexico and Viet Nam were able to join the CPTPP despite having significant state sectors.

The CPTPP’s rules on digital trade provide for the free flow of data. They prohibit data localization and the forced transfer of source codes. According to Henry Gao and Weihuan Zhou, the CPTPP’s exemptions for public policy and security may give China enough scope to implement its rules on data. China recently announced that it will pilot prohibiting the transfer of source code in its free trade zones.

Last year, China ratified two International Labour Organization conventions on forced labour. This was likely in anticipation of conforming with the CPTPP’s labour rules.

Some of the key US officials that helped get China’s accession to the WTO through Congress – including Charlene Barshefsky, Mickey Kantor and Jennifer Hillman – have urged the Biden Administration to reset its trading relationship with China by joining the CPTPP. According to Kantor, who was both the US’s Trade Representative and its Secretary of Commerce, the CPTPP is the “best trade agreement ever negotiated” and he sees it as a platform that would allow the US and China to address bilateral trade irritants.

In summary, China’s accession to the WTO was no mistake. It benefited China as well as its trading partners. China behaved as a responsible stakeholder within the WTO’s rules. To the extent that the rules of the international trading system need revising, China’s accession to the CPTPP provides a golden opportunity for an upgrade. Let’s hope the international community is up to the challenge.