A Tough Summer for China’s Youth

A Tough Summer for China’s Youth(Yicai Global) June 12 --Young people in China are facing challenging times.

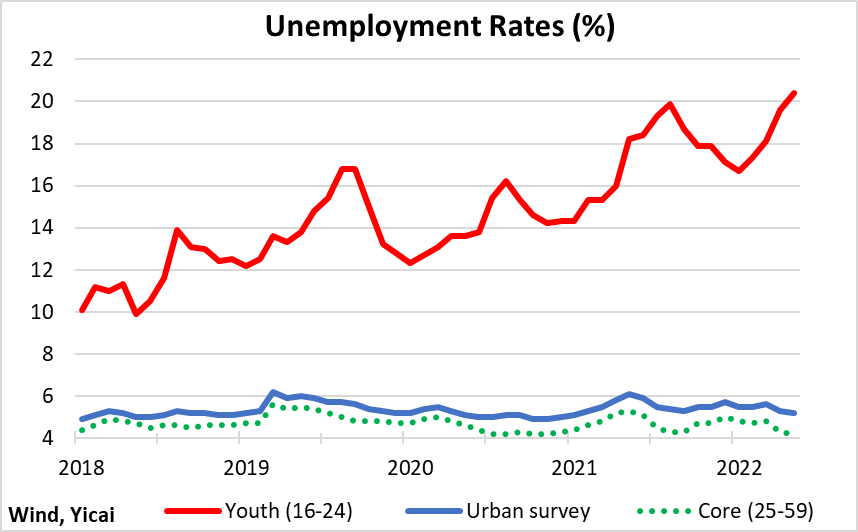

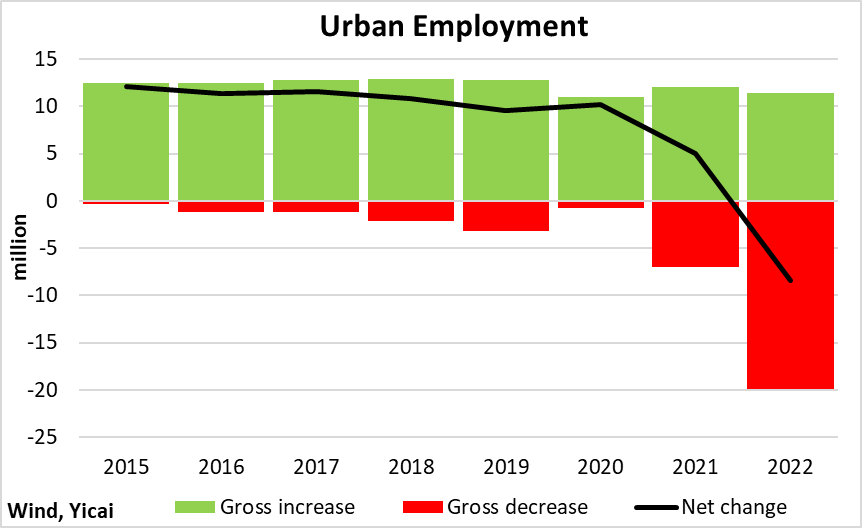

The National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) reported that the youth unemployment rate rose above 20 percent in April – a record high for this series, which begins in January 2018 (Figure 1). The unemployment rate for those 16-24 was 16 percentage points higher than for core workers aged 25-59 and this gap suggests some bifurcation in the Chinese labour market.

Figure 1

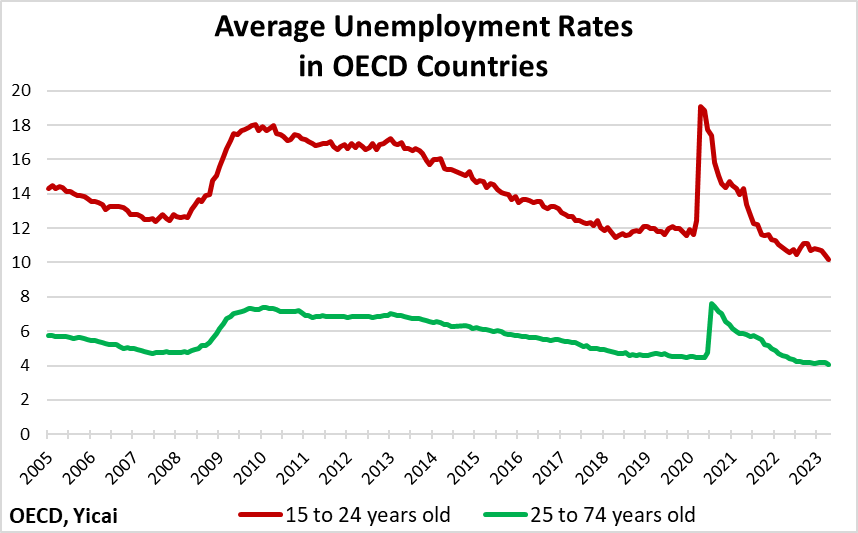

It is not unusual to see unemployment rates for young workers well in excess of those for more seasoned ones. On average, in OECD countries, the unemployment rate for those aged 15-24 has been 14 percent, 8 percentage points higher than for workers aged 25 to 74 (Figure 2). Still, the current gap in China’s unemployment rates remains comparatively large. To understand why youth unemployment in China is so high, it is worth examining both the supply of and the demand for labour.

Figure 2

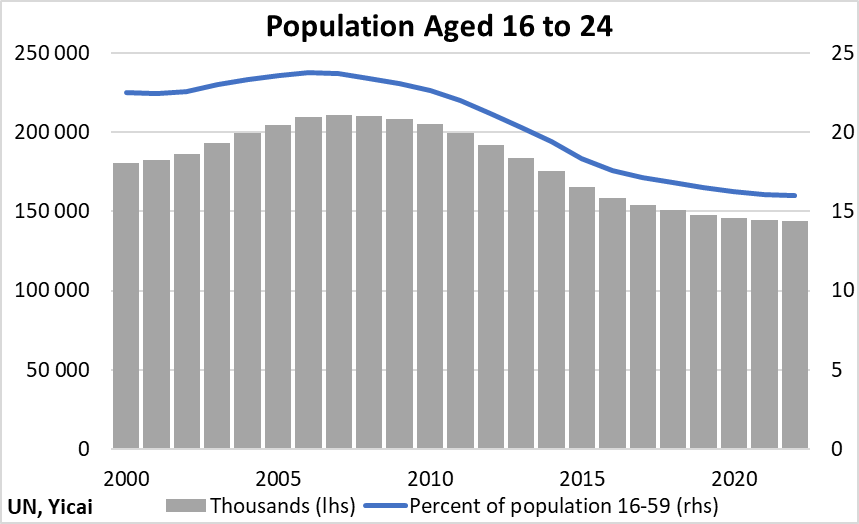

China’s working-age population – composed of those aged between 16 and 59 – began to shrink around 2010. The population aged 16 to 24 peaked slightly earlier and has declined more rapidly. In 2022, those aged 16-24 accounted for 16 percent of the working-age population, down from 24 percent in 2007 (Figure 3). With the supply of young people falling, the rising youth unemployment rate suggests that the demand for young workers is falling even faster.

Figure 3

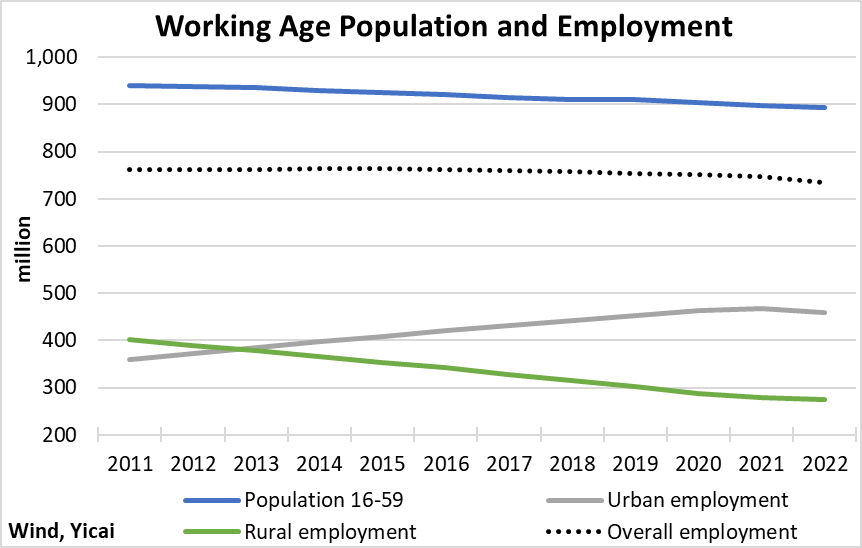

Between 2011 and 2022, the working-age population and overall employment fell by 5 percent and 4 percent, respectively. In the face of falling labour supply, China was able to maintain robust economic growth by shifting workers from rural to urban areas. Between 2011 and 2022, employment in the countryside fell by 32 percent while it rose by 28 percent in the cities, where workers’ productivity is higher (Figure 4).

Figure 4

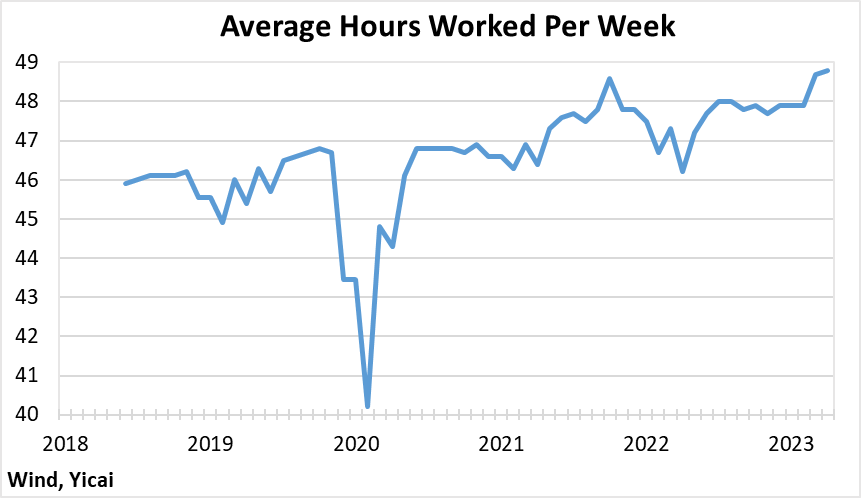

Urban labour demand slowed with the outbreak of the pandemic. The government targeted the creation of 9 million new urban jobs in 2020 and 11 million in both 2021 and 2022 and these targets were exceeded by comfortable margins. However, these targets are set in terms of “gross” new jobs. In the last two years, the pandemic and the associated public health measures led to relatively large “gross” job declines. In fact, last year urban employment declined on a “net basis” for the first time in recent history (Figure 5).

Figure 5

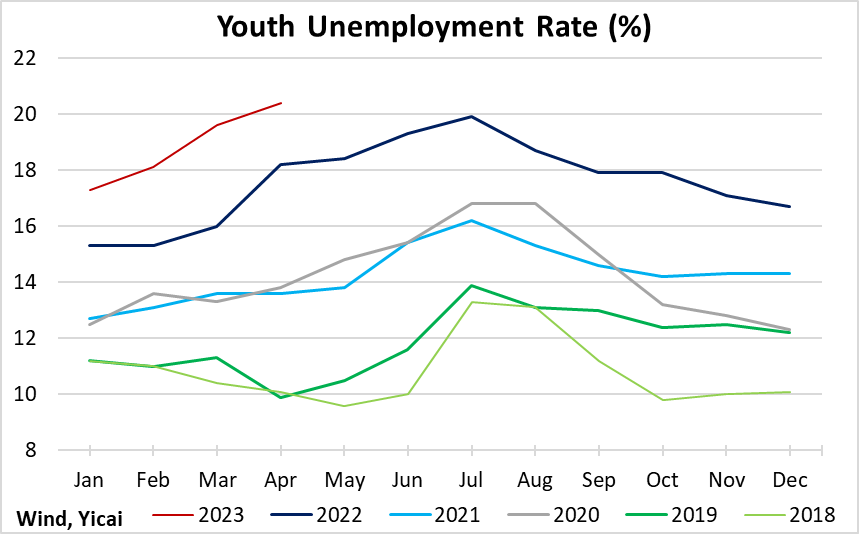

Some of the decline in labour demand is likely due to uncertainty over how rapidly the economy might recover from the pandemic. China’s labour law gives workers a high degree of protection and laying off employees than in other countries. In these uncertain times, employers have chosen to work their existing staff more intensively rather than take on new employees (Figure 6). This strategy has worked to the disadvantage of young and inexperienced job seekers.

Figure 6

To get a nuanced view of how Chinese young people are faring, we turn to the surveys conducted by RIWI (), which uses patented, machine-learning technology to reach the broadest possible set of respondents, on a continuous daily basis, and across all regions of the country.

Averaging over RIWI’s surveys since January 2020, 63 percent of respondents aged 16-24 indicated that they were in the labour force. Twenty-eight percent said they were studying and 10 percent were engaged in other activities (Figure 7). The share of those in the labour force edged up from early 2020 to mid-2021 and has remained fairly stable since then.

Figure 7

Sixty percent of the young survey respondents in the labour force were working full-time. About a quarter was working part-time and 16 percent were looking for work (Figure 8). The share of those looking for work is consistent with the average youth unemployment rate reported by the NBS since January 2020. Whereas the NBS’s data show a rising trend, RIWI’s survey data show a fairly stable unemployment rate.

RIWI surveys individuals employed part-time to understand their motivations for choosing this type of work. Most respondents 16-24 indicated that they chose to work part-time, either because they like the job they are doing or because they value its flexible hours. However, about a quarter say that they are working part-time because they are unable to find full-time jobs. This indicates a significant amount of youth under-employment.

Figure 8

RIWI’s data indicate that youth unemployment may be a bigger problem in the countryside than it is in the cities. More than 40 percent of the young respondents with urban hukou say that they are employed full-time, about 10 percentage points more than the young people in rural areas (Figure 9). To manage their employment challenges, rural youth are more likely to stay in school than their urban counterparts.

Figure 9

RIWI’s data suggest that more education does indeed improve one’s likelihood of finding full-time work. Since January 2020, 49 percent of the young respondents with bachelor’s or master’s degrees reported working full-time. This compares to just 35 percent for respondents with lower levels of education (Figure 10). The data show a worrying decline in the share of highly-educated young people that are employed full-time since December 2022. This may just be a seasonal effect – we see something similar the previous year as well. Nevertheless, it could indicate a further deterioration in young people’s employment prospects and should be monitored closely.

Figure 10

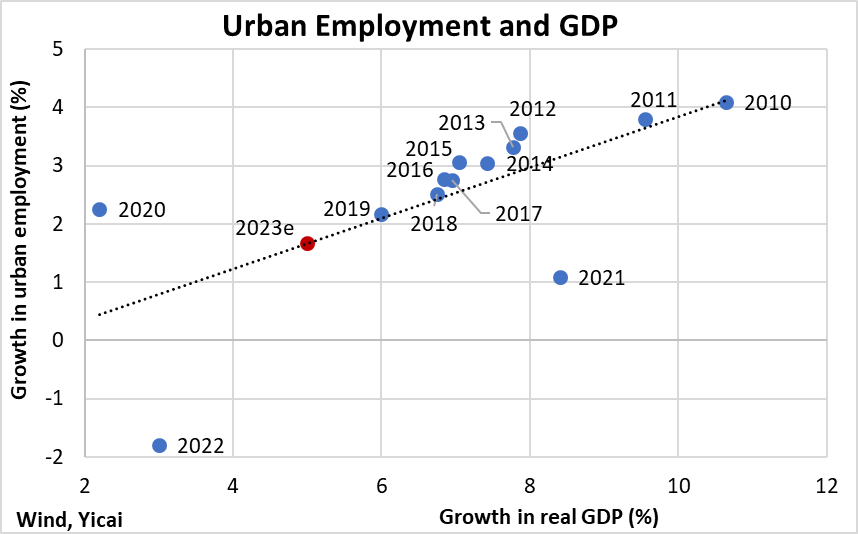

The macroeconomic data point to the likelihood of improving employment prospects this year. Between 2010 and 2019, there was a pretty close correlation between the growth of GDP and that of urban employment (Figure 11). In 2020, the economy slowed sharply but employment growth remained robust. That situation reversed in 2021 as the economy recovered but employment growth was insipid. Last year, GDP growth was weak and urban employment fell.

If GDP growth this year were to reach 5 percent, then urban employment would increase by 1.7 percent and it would reverse the last two years’ declining trend.

Figure 11

Unfortunately for China’s young people, their employment prospects may deteriorate further before they improve. The youth unemployment rate has a strong seasonal component, which peaks in July each year (Figure 12). Hopefully, as the recovery becomes more entrenched, employers will become more confident and willing to engage additional workers. This would improve the prospects for stronger youth employment in the second half of the year.

Figure 12

In sum, China’s youth unemployment problem stems from weak labour demand, which comes from a slowing economy and widespread uncertainty. Employers’ reluctance to engage new staff falls disproportionately on young, inexperienced workers. To some extent, young people can make themselves more attractive to firms by learning more skills. There may also be a role for policy to ensure that those who want to further their education have every means to do so.