5G and the Competition to Win the 21st Century

5G and the Competition to Win the 21st Century(Yicai Global) Aug. 9 -- Imagine two countries that are in competition to “”.

The roads in the first country are unpaved and cars can’t travel faster than 20 kilometers per hour. In contrast, the second country boasts a network of state-of-the-art expressways that permit safe speeds of up to 200 kilometers an hour. Which country would you bet on to win that competition?

In fact, the roads in the world’s major countries are pretty similar. But significant differences are beginning to emerge in their information super-highways, in particular how quickly they are adopting the fifth-generation standard for broadband cellular networks (5G).

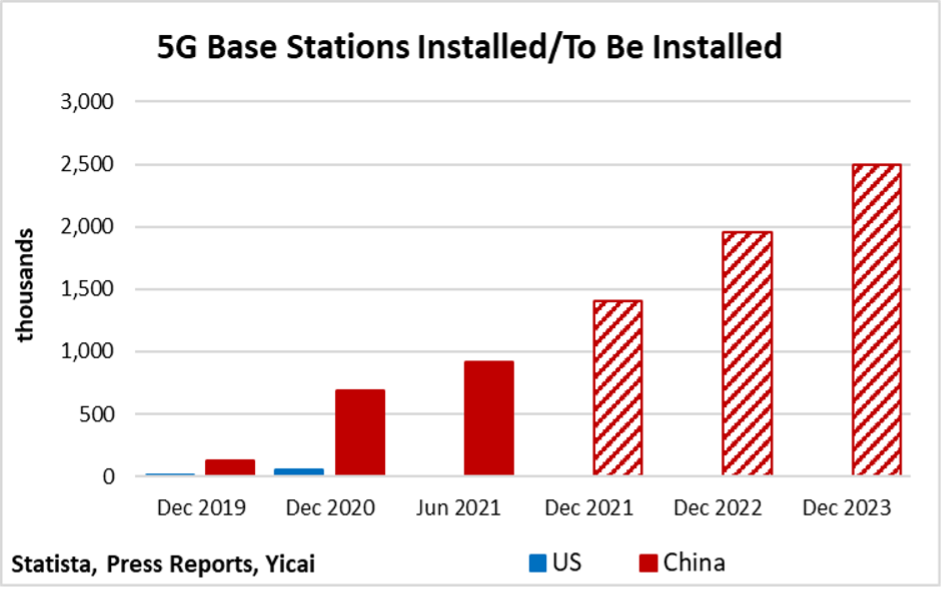

As of the end of 2020, China had installed close to 700,000 5G base stations. By last June, that number had risen to just under a million, and 1.4 million are expected to be installed by the end of the year. In July, 10 key government bodies unveiled a for China’s 5G development. As part of that plan, China aims to have 18 5G base stations installed for every 10,000 people – about 2.5 million in total – by the end of 2023. While it is difficult to obtain definitive information, the US had only installed something like 5G base stations by the end of last year (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Why is 5G so special?

According to the (ITU) – the United Nations’ specialized body for information and communication technologies – a 5G network will offer mobile users data at a rate of 100 megabits per second, or ten times faster than via 4G networks. The ITU says that 5G networks will be able to support 1 million devices per square kilometer, compared to 4G’s 100,000 devices. Finally, the ITU estimates that it will only take one millisecond for data to go from your device to the main server and back again. That’s down from 10 milliseconds for a 4G network.

A 4G network essentially facilitates the exchange of information between people. Taking mobile communication a step further, 5G’s superior capabilities will permit the rapid and accurate exchange of large quantities of data among machines. For example, your self-driving car will take you around town safely because it will be able to talk to other cars, to traffic signals and to satellites.

Given 5G’s potential to create smart factories, smart cities and smart medicine, why aren’t other countries rolling out the technology as fast as China?

There appear to be two main obstacles.

First, there is a basic incentive-compatibility problem. A first-rate mobile network is a key piece of infrastructure that – like a highway system – offers significant returns to the entire economy. But only a small portion of these returns accrue to the telecom firms who create the network. Moreover, these firms need to make huge up-front investments in the face of uncertain revenues and it is not clear that they can make . So, there is a disconnect between the network’s social and private returns.

Second, 5G suffers from a sort of chicken-and-egg problem. Since the 5G system is not yet fully in place, few 5G-specific applications have been developed. And, since there aren’t many applications, there is little demand for the network. Little demand for the network means that there are limits to how much the telecoms can charge for service, thus delaying 5G’s development.

Much of the cost that telecoms incur arise from the purchase of the rights to use certain radio frequencies (spectrum). Eric Schmidt, Google’s former Chief Executive and Chairman, worries that these expenses are retarding network development. In a Financial Times , Schmidt estimated that it would cost USD70 billion to build the one million stations needed to give the US a functional 5G system. However, US telecoms are spending more than this on spectrum auctions alone. These, Schmidt suggests, are more focused on raising government revenue than creating infrastructure. He proposes that Congress use the proceeds from the spectrum auctions to provide funding for the 5G network.

A further complication arises from the US’s lack of a homegrown telecommunication equipment provider. The world’s five main players – Huawei, ZTE, Samsung, Nokia and Eriksson –are Chinese, Korean, Finnish and Swedish. US telecoms face more when they purchase their equipment overseas.

China has solved the incentive-incompatibility problem by making 5G’s development and commercialization a national priority. To capture 5G’s potentially high social returns, it has catalyzed its telecoms, equipment providers and industrial firms. Pilot schemes were already envisaged during the 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020). More specific policy guidance was provided in for local governments to develop 5G-based “industrial internet”.

Being at the forefront of a new technology does mean undertaking a high-risk, high-return strategy. But this is a gamble that the Chinese government is willing to take. Liu Liehong – a Vice-Minister at the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology – that China will need to spend CNY1.2 trillion (USD187 billion) to 2025 on constructing its 5G network. If it is successful, Liu believes that investment could result in CNY2.9 trillion in additional economic value added.

In an effort to get around the chicken and egg problem, July’s Action Plan proposes a “demand-driven supply, supply-created demand” model. The government will proceed simultaneously along two tracks: (i) encouraging the development of the system through targets for base stations and user penetration and (ii) promoting 5G applications in various commercial sectors. The Action Plan hopes to build off of the early successes of using 5G in , , and .

Now imagine two countries that are cooperating to survive the 21st century.

One country becomes the first to exploit a new technology. Do you think that there would be important lessons and positive spillovers for the second country?